If you are keeping score, this is my 10th blog post detailing a 7-day, 6-night luxury cruise aboard La Belle Epoque, a hotel barge in the fleet of European Waterways. The last post in this series, A Barge Cruise on the Burgundy Canals, Day 4, Part 1 Ancy-le-Franc, Argenteuil-sur-Armançon, Noyers-sur-Serein, Ravières, detailed a busy day of exploring a small town and a small-town market, savoring a gourmet lunch and cruising down the scenic canal, docking just in time to enjoy a fabulous sunset.

But we still had one more important task to complete that day: dinner! While Katy Jennings, our resident chef, made most of our meals, tonight she would get a break and we would get another look at what has officially been recognized as one of “The Most Beautiful Villages in France,” Noyers-sur-Serein.

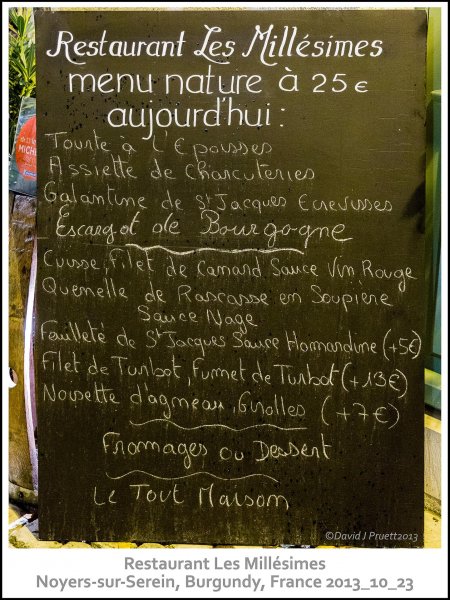

We had a leisurely morning to explore the village, but now we were much more focused. We were headed for Restaurant Les Millésimes (“The Vintages,” as in the vintage of a wine—a good omen!)

The restaurant was as beautiful as the rest of the village. It was also very dark, so you will just have to overlook the relatively poor quality of the images taken in the very low light. I always use only the available light when I take pictures in a restaurant as I do not want to disturb any other diners with flash or other lights.

You can see the white tablecloths, wine glasses, beautiful fresh flowers and, of course, a wine bucket full of chilled white wines.

They put together a nice long table for our party.

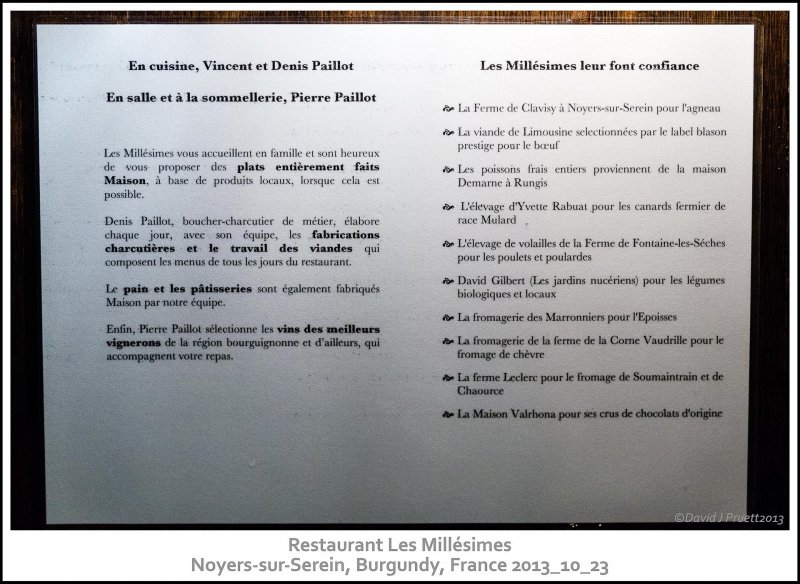

The restaurant posted a notice introducing all the staff as well as specifying the sources of most of their raw materials. For those of you who like to know where your food comes from, this is a restaurant for you. Virtually everything is local.

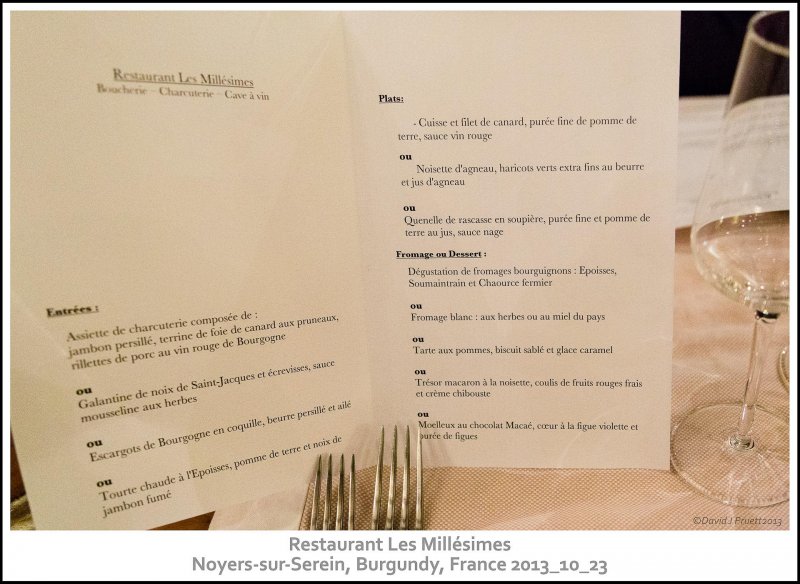

The menu was, not at all surprisingly, only in French.

Fortunately, I read menus in several languages that I do not otherwise understand very well, if at all. Some of our fellow travelers were proficient in French and the wait staff was helpful, so we managed.

Valeria got some help from Eric Bonal, whom you may recall from earlier posts about the trip. Eric was on board La Belle Epoque as a representative of The Wayfarers, a tour group that specializes in hiking tours all over the world. He is also a native Frenchman and a great lover of food and wine (but perhaps that is redundant).

We started with some delicious, warm bread to start; some type of Brioche, I think.

Spread with rich French butter it was amazing.

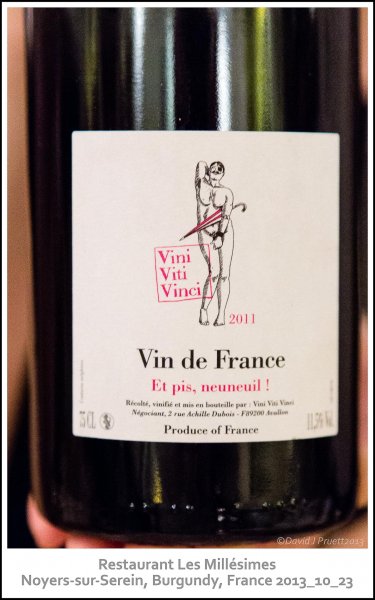

Of course a couple of wines, a red and a white, were selected for us. The red: 2011 Vini, Viti, Vinci, a simple Vin de France.

Vini Viti Vinci (Julius Caesar’s famous phrase: I came, I saw, I conquered) is a brand of wines produced by Nicolas Vauthier. Vauthier is a bartender turned winemaker who’s eclectic style has made his wines both trendy and confusing. He owns no vineyards and says he never will. He buys grapes primarily in northern Burgundy, but he does not limit himself to the standard Chardonnay and Pinot Noir that define the region. He started making biodynamic wines with natural yeasts and minimal manipulation before it was cool. He bottles over a dozen different wines in a given year. They tend to be very fresh and fruit driven with herbal and floral notes from the grapes and the stems that are included in the maceration (most winemakers remove the grapes from the stems before crushing and fermenting them). They are also low in alcohol and lend themselves to chugging as much as sipping. Like this one, they are often designated simply as a “Wine from France” since he does not pay much attention to the strict rules of grape type, location and so on that must be followed to earn a specific appellation. If one of his wines is labeled with a specific region and vineyard, they tend to be pretty obscure.

The wines may be about as famous (or infamous) for their labels as for their contents. They usually feature drawings of men or women in various states of undress, sometimes completely naked and in explicit poses. The one above is pretty tame.

This wine was, as it turned out, 100% Pinot Noir, but it was not like any other Pinot we tried on this trip. Very fruit-forward, almost Beaujolais like. Honestly not my favorite style, but I understand why it appeals to some.

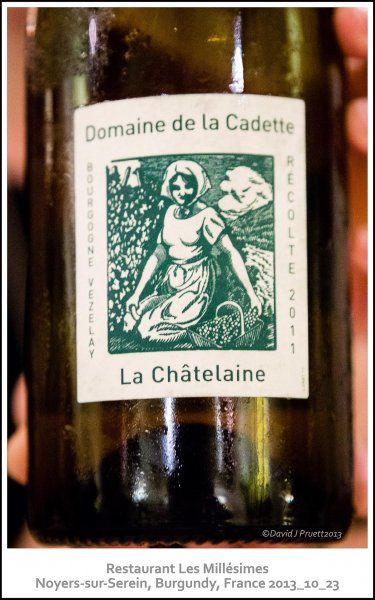

Our white was rather more conventional, but still outside of the mainstream of Burgundy, the 2011 Domaine de la Cadette La Châtelaine,Vezelay, Burgundy, France.

Vézelay is a small commune located west of the Côte d’Or (the main winemaking area in Burgundy) and south of Chablis (which is officially part of Burgundy but generally considered it’s own area). Vézelay was famous for its 11th century Abbey and, until recently, not much else. Vineyards were established there as early as the 9th century, but they were wiped out by phylloxera after World War I, as documented in the previous post in this series.

Things began to change in 1987, when Jean and Catherine Montanet decided to plant some vineyards and dedicate themselves to making high-quality wines. They bottled their first wines in 1990 and were almost immediately noticed by respected restaurants and wine authorities with orders for wines and positive reviews. In 1997, Bourgogne Vézelay became an officially recognized appellation. The Montanets continue to run Domaine de la Cadette, as they branded their wines, now with the help of their son, Valentin. They have been champions of organic farming and natural winemaking from the start.

La Châtelaine 2011 is 100% Chardonnay. It was light and crisp with good acidity—quite typical of their style. I had tasted other vintages of this wine, but I have never tasted their red Pinot Noir or their other white wine made with Melon de Bourgogne, a grape usually found in the Loire Valley (at least in France). It is grown elsewhere and more commonly called Muscadet. Since Melon de Bourgogne cannot be legally used to produce a Burgundy (ironic, given its name), the wine is called Melon de France.

Having enjoyed the bread and our first tastes of the evening’s wines, it was time to eat. We had a typical three-course, prix-fixe (fixed price) menu. There were three or four choices each for the appetizer, main course and dessert. I didn’t get a photograph of every one, but enough to give you a feel for what a classic French menu in a small French restaurant in the heart of Burgundy looks like.

Let’s start with a classic French dish that many Americans have learned to love, though many have not quite gotten past the “Ewwww!” stage. I’m talking about snails.

I do understand why some people will not touch them. The image of a slimy gray slug that hs been crawling through your garden landing on your plate is not inherently a pleasant one. I actually find snails (living ones) to be quite interesting. They can, in fact, be quite elegant and graceful, as this beautifully shot video shows. (Warning: if close-up photography of snails and other crawly things makes you squeamish, you might want to skip this one.)

Cooking the snail at home to be exactly like those we had in the restaurant is actually very easy. Here’s how it’s done.

Sourcing snails, at least in the US, is more of a problem. They need to be fresh and clean, not canned. One solution, and an economical one at that, is to catch snails in your own yard, if you have one. That was a revelation to Chef Gordon Ramsey. If you would like to try your hand at catching your own snails, here is how it’s done (small children optional, but handy for the manual labor).

OK, that’s more than most of you ever wanted to know about snails. I will only add that I do enjoy a few of them as an appetizer, but really don’t want to make a whole meal of them. These were perfectly cooked and delicious, but, then, almost anything covered in garlic and melted butter will taste pretty good.

A second appetizer was just as classically French, but is unlikely to draw many negative reactions except from those who don’t eat pork. Here is Tourte chaud à l’Epoisses, pomme de terre et noix de jamon fumé (Warm cheese, potato and ham tart)

This is nothing more than layers of potato, smoked ham and cheese wrapped in a flakey pastry. The cheese used here was Époisses de Bourgogne, the poster child for what are often referred to as “stinky cheeses”—rind washed, cow’s milk cheeses that are soft ripened. During the ripening process, the outside of the cheese (i.e., the rind) is washed with brine (salty water) and, in this case, Marc de Bourgogne, a brandy made in Burgundy by fermenting and distilling leftover grape skins, seeds, and the other solids filtered away from the juice used to make wine. I love this cheese, but neither Valeria nor I have ever met a cheese we didn’t like. The fact that it is melted in with the potatoes and ham helps mellow it out, so if you think it is too strong all by itself, you might like it this way. Here’s a one minute introduction to Epoisse from another fan of this cheese.

I’ll also share a simple recipe for an Americanized version of the potato, cheese, and ham dish. It is actually sort of a riff on lasagne, so maybe it’s an Italian-American version? It calls for Mozzarella cheese and simple boiled ham (and bacon—yum!), but don’t be afraid to up the flavor quotient by substituting other cheeses and more flavorful ham. And more bacon. Always more bacon. Consider adding some minced garlic to the cream mixture and maybe some herbs. The basic technique is simple, but you can elevate the dish easily as well.

The next appetizer choice was also a classic, but perhaps more controversial than potatoes, ham and cheese: Charcuterie: jambon persillé, terrine de foie gras canard aux pruneaux, rillettes de porc au vin rouge de Bourgogne (ham & parsley terrine, Terrine of foie gras & prunes, pork rillette)

French terrines can be thought of (not 100% accurately, but close enough) as fancy versions of the all-American meatloaf. For those of you who are not familiar with the American version, it is made with a mixture of ground meats—beef, veal and pork are classic, turkey and chicken have become common—flavored with onions, herbs, perhaps other diced or shredded vegetables, with bread crumbs or cracker crumbs and an egg used to bind it all together. After mixing, everything gets formed into a bread pan (a “loaf of meat” instead of “a loaf of bread”) and baked. Depending on the skill of the cook, it can be tasteless and as heavy as lead or have a light texture and be full of flavor.

A French terrine follows the same general recipe. Duck, foie gras (duck or goose liver), chicken livers and ham or some other form of pork are the most common meats used. I don’t think I have ever seen one with beef, but they must exist. Seafood and vegetable terrines are also common. The ingredients are generally not as finely ground as for a meatloaf or a pâté (which is usually made from very finely ground meats or vegetables). The primary thing that makes a terrine a terrine, however, is the dish it is based in: a terrine. A terrine is a glazed earthenware dish that has straight sides and a tight lid. Let’s take a look at the examples served here.

In the center of the plate in the image above are two terrines. The one on top (darker brown, white stripes on the edge) is a terrine de foie gras canard aux pruneaux—a terrine made with duck liver and prunes (the little black specks). The white lines around the outside are from a fatty netting called caul fat that can come from a cow or pig. It is wrapped around a dish to baste it and help keep it moist. There was very likely a nice dash of cognac in the recipe as well. Prunes are often part of a foie gras terrine as the sweetness helps balance the rich fattiness of the dish. Prunes stuffed with foie gras are delicious and can be ordered from D’Artagnan.

If you don’t like foie gras, as many people do not for a variety of reasons, the second terrine may be more to your liking, jambon persillé, or ham & parsley terrine. Notice that the chunks of ham are quite large in this preparation. It is very common to see this dish made with the meat from ham hocks (i.e., ham shanks), pigs feet or ham. The pork is first cooked, they the meat cut or shredded into fairly large pieces and packed into the terrine. Gelatin made with a flavorful pork stock and tons of parsley is poured around the meat and allowed to set, as you can see in the pockets of green. No, it hasn’t gone moldy, it’s made that way!

The third terrine is rillettes de porc au vin rouge de Bourgogne (pork rillettes with red wine). Rilletes are simply meat (pork, duck and chicken are common) that are slow-cooked, often in fat, with flavorings such as onion, carrot, garlic, salt, pepper and thyme, until they are fall-apart tender. The meat is shredded and packed into a container (e.g. a terrine). Some the flavored fat from the cooking process is added to bind the whole thing together, although some lighter, modern version use gelatin instead.

All of these variations are traditionally served with some thin slices of bread or toast, some cornichons (small French dill pickles) and Dijon mustard.

The plate we were served included two sausage slices and a piece of cheese, but I don’t remember what these were.

If you’d like to know more about making pâtés and terrines, grab a glass of wine and spend about 30 minutes with the Grand Dame of French Cooking, Julia Child, in an episode of her very first cooking show (and one of the first cooking shows on US television), The French Chef.

These were the first such recipes I ever made, so they are a bit nostalgic for me.

The fourth option for an appetizer was another variation on the general theme of terrines and pâtés, a Galantine de noix de Saint-Jacques et écrevisses, sauce mousseline aux herbs (Galantine of scallops & crayfish with herbed mousseline sauce).

A classic galantine is made with chicken and is quite time consuming. The bird is skinned and the meat separated from the bones. The skin is laid out and the breast meat, perhaps filleted or pounded thin, is arranged on top. A layer of a pâté-like mixture made by grinding up the rest of the meat, possibly with other meats, and flavored with garlic herbs, and other aromatics is added next. The whole thing is carefully wrapped up in the skin and poached in a rich stock. Finally, it is cooled, sliced and served cold or at room temperature.

This galantine was made with scallops and crayfish. How do you skin those? Well, you don’t, so the chef used thin pieces of salmon as the “skin.” A fine mousse of scallops and crayfish was studded with scallop and crawfish pieces to make a modern seafood variation on the original chicken dish, which was invented in the late 1700s—about the time of the founding of the USA and the French Revolution.

Mousseline sauce (the small, log-shaped item that looks a bit like butter at the top of the plate) is just Hollandaise sauce (of Eggs Benedict fame) into which has been folded some whipped cream. This is a seafood dish, but don’t be fooled into thinking it is “light.” The seafood mousse is made with heavy cream and the Mousseline sauce has plenty of butter, eggs and cream.

I noticed some basic condiments were on standby just in case someone wanted an extra drizzle of olive oil, some freshly ground black pepper or a sprinkle of salt.

Next up, our entrées. Valeria and I, as we always do, ordered two that we would share. Valeria started with the Noisette d’agneau, jus d’agneau, haricots verts extra fins au beurre (Lamb in lamb jus, green beans in butter).

Growing up in a middle class home in the midwestern USA, lamb was not something I ever saw at the dinner table when I was young. Once I started cooking and developed into a foodie, it became one of my favorite meats. This was a classic, simple French presentation of leg of lamb: roasted rosy-rare and served with mashed sweet potatoes, mashed white potatoes and green beans. There was just enough intensely flavored jus to moisten and flavor each bite. No fancy plating or exotic ingredients, just simple ingredients, perfectly cooked.

I ordered another meat I never knew growing up, Cuisse et filet de canard, purée fine de pomme de terre, sauce vin rouge (leg & breast of duck, mashed potatoes, red wine sauce).

This preparation was a little more complicated because the duck leg was confit, which means it was slow-cooked in fat, spices and herbs, much like the pork for the rillettes in the appetizer course. Confit is an ancient preservation technique. Once cooked, the meat is just left to cool in the fat, which sealed it from the air and bacteria. Reheated, you have meltingly tender, flavorful duck meat.

You can make duck confit at home in your slow cooker, if you like. It is not at all difficult, but it does take time. Here’s how.

The breast of the duck could not have been cooked more differently. It was simply pan fried until the meat was just past rare and skin was crisp. The menu claimed there would be mashed potatoes on the plate, but it was a neatly carved piece of boiled potato accompanied by some simply boiled or steamed carrots and some sautéed mushrooms. The red wine sauce was rich and delicious. Probably a pan sauce made with some demi-glace (basically a reduced, concentrated stock) and red wine.

Time for dessert. While Americans are justifiably proud of the apples grown in the US and the recipes that showcase them, the French take a back seat to no one for using this fruit. From hard cider to Calvados (apple brandy), in sweet tarts and custards and in savory meat dishes, French cuisine takes the apple in every possible direction. Nothing is any better than a relatively simple apple tart.

The tart was made with a thin, flakey crust, a layer of caramel, artfully arranged, thinly sliced apples, a nice hit of cinnamon and, I think, a touch of nutmeg.

Ice cream is always a good thing with apple pie. Plain old vanilla is fine, but the house made caramel ice cream was delightful.

Valeria’s dessert choice was very French and equally delicious: Trésor macaron à la noisette, coulis de fruits rouges frais, et crème chibouste (Treasure cookie with fresh red fruit sauce and pastry cream).

This was a riff on the (to me, inexplicably) popular French macaron cookies. These multi-colored sandwich cookies are sort of a cross between a meringue and regular cookies and, for whatever reason, I have never developed a taste for them. Millions of people have, however, so you see them everywhere in France.

This one was a little more cookie-y to me and I liked the fruit and pastry cream “treasure” in the center.

Dinner in a good French restaurant is never done until the mignardises (small sweets and pastries traditionally served with coffee after a meal) are on the table.

I had not had a chocolate dipped, candied citrus peel in a long time and had forgotten how good they are. The fig gelées (jellies) were tasty, too, but I really liked the citrus peels.

There were various paintings, carvings and other works of art all around the restaurant. Here are a couple.

The first one appears to be someone harvesting the grapes and the second looks like a woman pressing the grapes in a wooden barrel with her feet.

This was a delightful excursion in a town we had a chance to actually get to know a bit when we spent the morning there. The restaurant was as classically French as it could be, which, for me, is a good thing.

Then it was back to La Belle Epoque for a quick digestif and a good night’s sleep.

In the next chapter of this series, A Barge Cruise on the Burgundy Canals, Day 5, Part 1, A Balloon Ride Over Burgundy, we’ll be up early to float over Burgundy in a hot air balloon. See you there!

All images were taken with a Canon 5D Mark III camera and a Canon EF 24-105mm f/4 L IS USM Lens or a Tamron AF 28-300mm f/3.5-6.3 XR Di LD VC Aspherical (IF) Macro Zoom Lens (now discontinued; replaced by Tamron AFA010C700 28-300mm F/3.5-6.3 Di VC PZD Zoom Lens) using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.

The author has no affiliation with European Waterways or any of the locations and products described in this article.

Pingback: A Barge Cruise on the Burgundy Canals, Day 4, Part 1 Ancy-le-Franc, Argenteuil-sur-Armançon, Noyers-sur-Serein, Ravières

Pingback: A Barge Cruise on the Burgundy Canals, Day 5, Part 1, A Balloon Ride Over Burgundy