In my last entry in this series, A Barge Cruise on the Burgundy Canal, Day 5, Part 2, Ravières to Montbard, I covered many of our activities on the fifth day of our cruise on the Burgundy Canal on the European Waterways luxury hotel barge, La Belle Epoque. I skipped over our visit to the 12th century Cistercian monastery, the Abbey de Fontenay, since it deserved a post all its own. Here is that post!

The Abbey of Fontenay was founded by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), a member of the strict Cistercian Order of the Roman Catholic Church, in 1118. We’ll get to the history and architecture of the Abbey in a moment, but Mother Nature dominated our first look as her beautiful fall colors were on glorious display as we pulled up to the entrance.

This centuries-old crucifix was also just off the parking lot outside the entrance to the Abbey.

I don’t know when this particular piece was erected, but I wonder how many pilgrims, monks and nobles have paused to touch it and perhaps say a prayer before passing through the entrance arch to the Abbey?

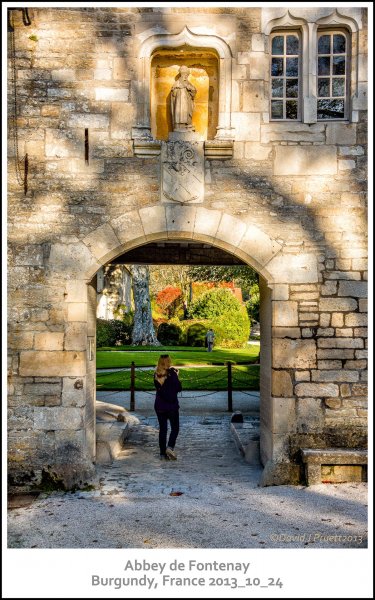

I was not able to identify the figure in the statue above the entrance.

He is wearing a Bishop or Pope’s mitre (hat), so perhaps it is Etienne de Bagé, Bishop of Autun, who was Saint Bernard’s maternal uncle and who donated the land the Abbey is built on. Or perhaps it is Ebrard of Arundel, Bishop of Norwich, who fled to the Abbey in 1139 to escape persecution and who used his fortune to fund much of the early construction of the Abbey. Or maybe it is Pope Eugene III, who consecrated the church is 1147. All just guesses; please message me if you know who this is.

The Cistercian Order was founded in an attempt to to get back to the fundamental ideas of monasticism as codified by Saint Benedict around 500 A.D. Monks were to live simple lives of prayer and work (and, according to Saint Benedict, “to work is to pray”). They were to be isolated from wealth and the world. Human beings are rarely able to live up to such high ideals, however, and monasteries eventually began to acquire land and wealth and become more integrated into the local community.

The Cistercian monks built their monasteries in isolated, often difficult to reach, locations far from villages. The site of the Abbey of Fontenay was mostly swamp and marshland when it was donated to the order and it was located in the middle of nowhere. For the first 100 years or so the Abbey worked very much as Saint Benedict and Saint Bernard envisioned, populated with male monks devoted to prayer, study and work, isolated from and independent of the rest of the world. As the 13th century progressed, interaction with local nobles increased, as did the wealth of the Abbey. Nor was the location isolated enough to protect the Abbey from the Hundred Years’ War (1337—1453), the Wars of Religion (1562—1598) and, finally, the French Revolution (1789—1799). By the late 1700s the Abbot of Clairvaux, Peter VI, had to take action to stop gambling, hunting and prostitution at Fontenay.

The life of the Abbey of Fontenay as a working monastery ended on October 29, 1790, when the last eight monks left as the French Revolution secularized almost all religious properties. Unlike many sites, however, the Abbey was not destroyed but turned into a paper mill. This and other industrial uses largely preserved the site, which was declared a French Historical Landmark in 1852. In 1906, Edouard Aynard bought the site and decided to remove all industrial activity. In a major restoration from 1906—1911, Aynard restored the Abbey to as close to it’s medieval from as possible. Restoration work has continued to the present. The Abbey was was designated as a Unesco World Heritage Monument in 1981.

The Abbey has also been used as a location for many movies, including:

– Poker d’As (1928), by Henri Desfontaines

– The Fighting Musketeers (1961), by Bernard Borderie

– Angélique (1964), by Bernard Borderie with Michèle Mercier, Robert Hossein, and Jean Rochefort, followed by Angélique: the Road to Versailles (1965) and Angélique and the King (1966)

– Cyrano de Bergerac (1990), by Jean-Paul Rappeneau with Gérard Depardieu

– Les Aventures de Philibert, capitaine puceau (2011), by Sylvain Fusée

Only a few of these are currently available in the US. Ironically, none of them portray anything like a monastic life.

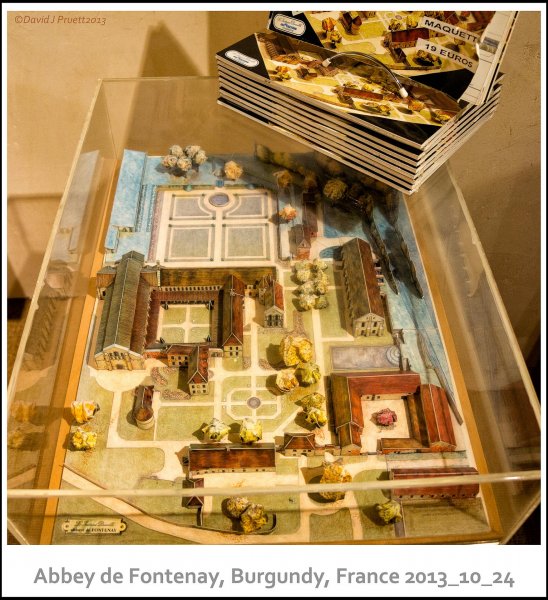

The Abbey is laid out following a design that was developed in the early 9th century (possible before) and was largely followed until the end of the 18th Century.

The cluster of white buildings in the center left include the cross-shaped church on the far left, oriented (more or less) east and west. Connected to the church and enclosing the cloister are the chapter house, the monks’ room, a warming house and the abbot’s lodging. The refectory (communal dining area) and kitchen have not survived. These areas were supposed to be reserved for the monks. The monks’ dormitory was above the chapter house and scriptorium (more about all three later), directly connected to the church. To the right (south) are an infirmary, forge and guest house. This is where lay workers and guests were to stay, theoretically isolating the monks from everyone else. At the entrance (bottom of the picture) was the entrance gate, a visitor’s chapel a bakery and the dog kennels.

Here is a shot of the entrance gate from inside (which I guess makes the exit gate).

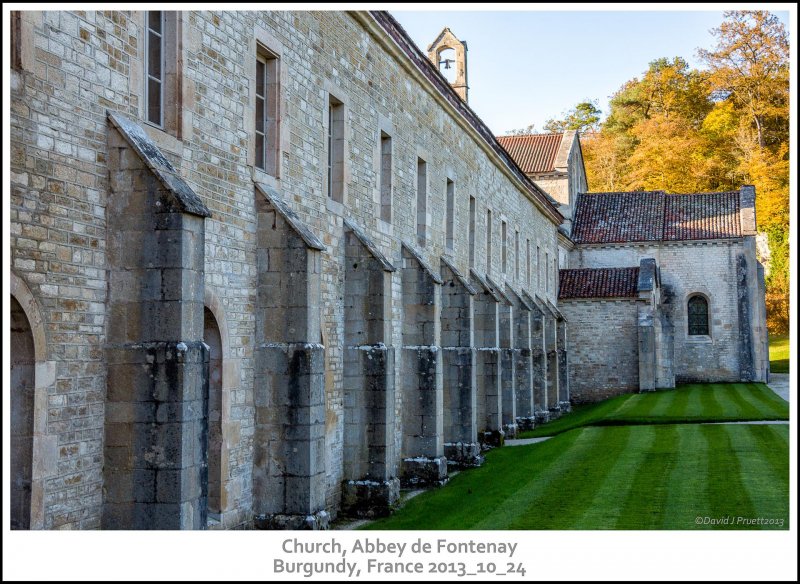

The building on the right housed the chapel and bakery. Today there is also a library and lapidary (stone and gem) museum. As you enter the Abbey, the south side of the church and cloister complex greets you across a garden area.

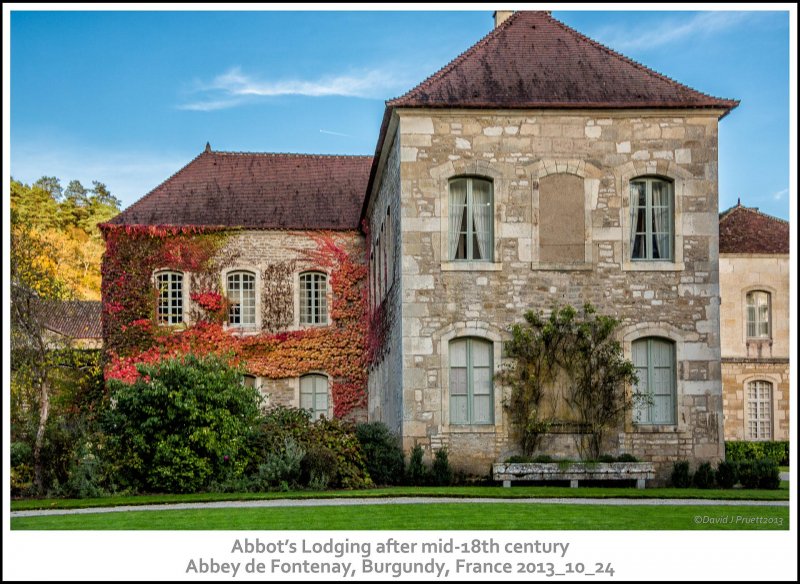

The building facing us in the middle of the picture was the monastery’s vault. To the left is the abbot’s lodging that was built in the mid-18th century.

The abbot (“father,” basically the head monk in charge of the monastery) was supposed to live the same, simple life as the rest of the monks. The selection of the abbot has been done many ways over the centuries. In more isolated monasteries the monks elected the abbot, perhaps subject to confirmation by an archbishop or the Pope. Sometimes the archbishop or the Pope appointed the abbot directly. In 1516 an agreement was reached between Pope Leo X and King Francis I of France which allowed the King to appoint the abbots in France. This radically changed the office. The so-called “commendatory abbots” often did not even live at the monastery. The law dictated how the revenue of the monastery was to be divided between the abbot and the monks, which often left the monks with barely enough money for food and clothing. The abbot was charged with maintaining the abbey, but he was often far more interested in maximizing how own revenue, so money for maintenance was minimal, money for improvements usually nonexistent. This was a major factor in the decline of the great monasteries in the years to come.

The first commendatory abbot at Fontenay was appointed in 1547. In the early 1800s, the luxurious residence pictured above was built for the abbot. The monks, meanwhile, continued to sleep on straw on the floor.

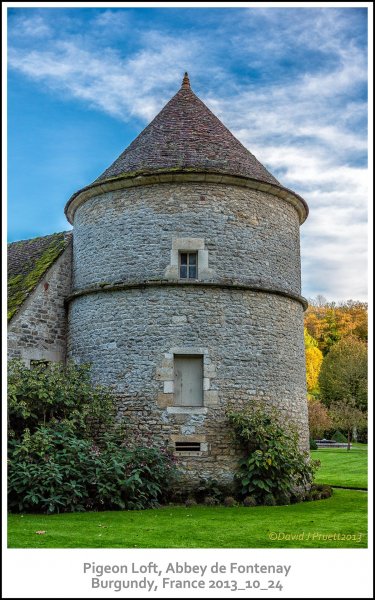

Continuing left from the entrance, we see the pigeon loft.

Pigeons were an important source of meat for the monks.

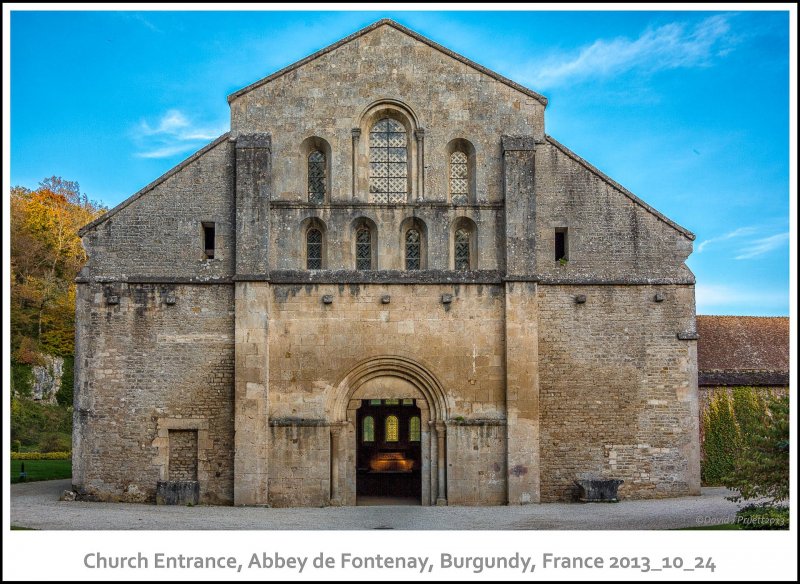

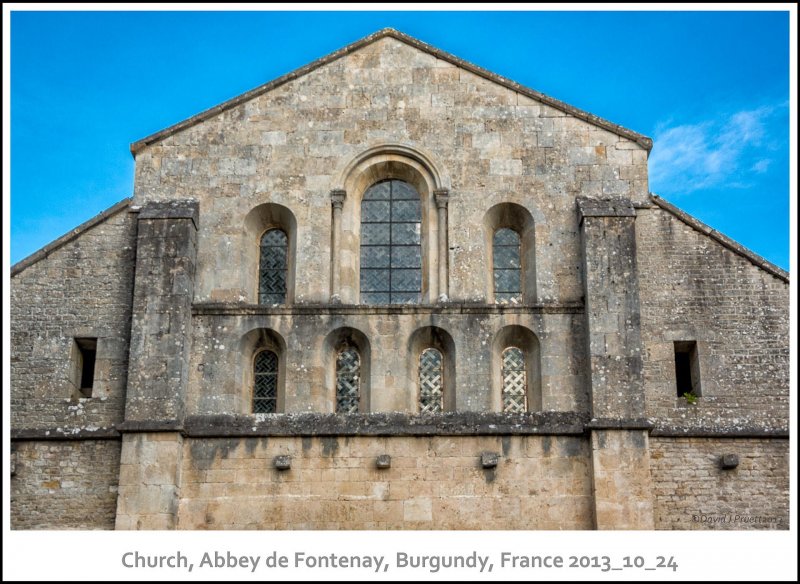

A little more to the left of the entrance and we see the most important building on the site, the church.

The church, of course, was the heart of any monastery. Construction of the church began in 1139 and it was dedicated less than 10 years later on September 21, 1147 (exactly 806 years before the day I was born) by Pope Eugene III. This was remarkably fast at a time when similar buildings took decades to construct. The design was a traditional Latin cross with carefully built, but very plain, walls, doors and windows. Saint Bernard insisted that the churches in Cistercian monasteries be as plain as possible so as not to detract the monks from their prayers. Even the cross was eventually removed. You may recall that Bernard was from the monastery at Clairvaux. Pope Eugene III was also a Cistercian monk there before moving up the ecclesiastical ranks.

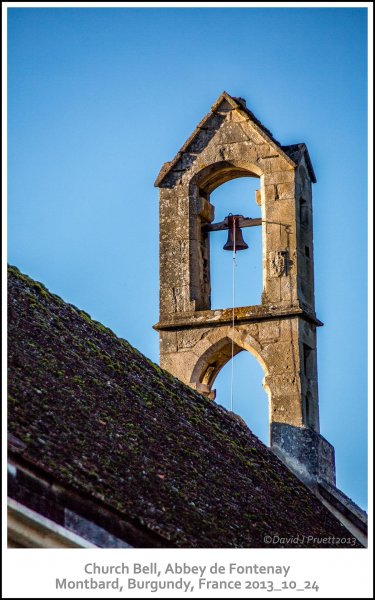

Bernard did not add the usual bell tower to the church as he thought the sound too distracting. There were some small bells used to call the monks to prayer. A small bell tower was added to the structure sometime later.

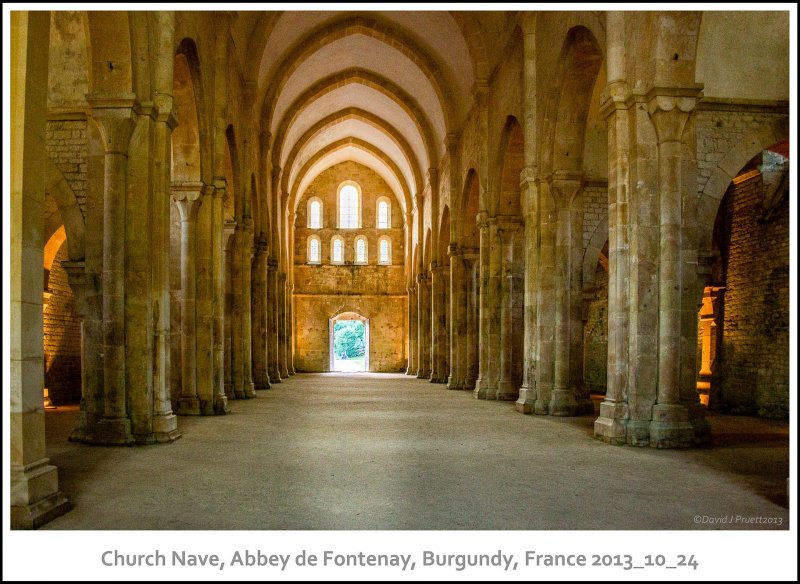

The nave or main area of the church was similarly plain, yet beautiful in its simplicity.

Note the lack of ornamentation of the columns.

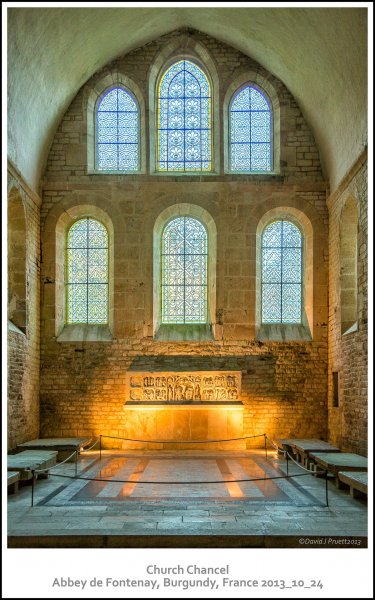

The chancel (the front part of the church where the altar is placed and the minister conducts services) was also relatively plain.

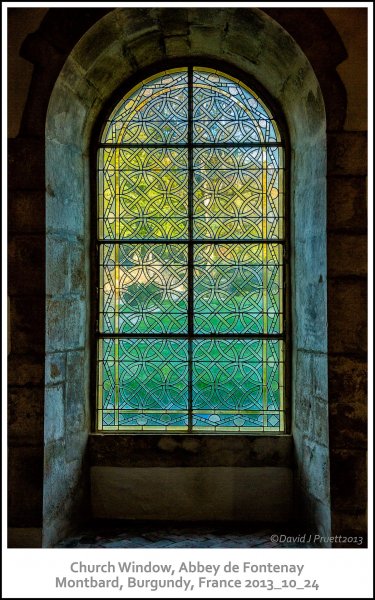

I don’t know if the stained glass windows are representative of what would have been in the church as built or not, but they were designed so the morning sun would illuminate the chancel while leaving most of the church relatively dark. Certainly the design of the windows we see today is simple enough that it may have won Saint Bernard’s approval.

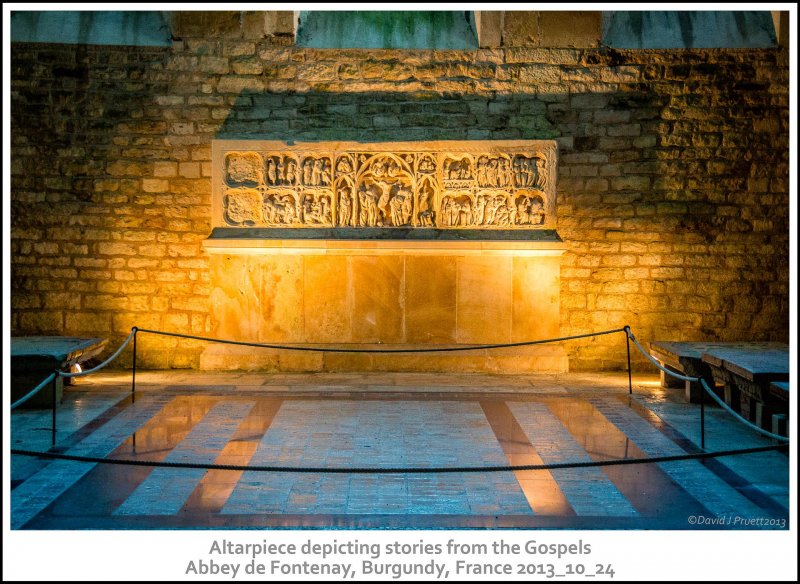

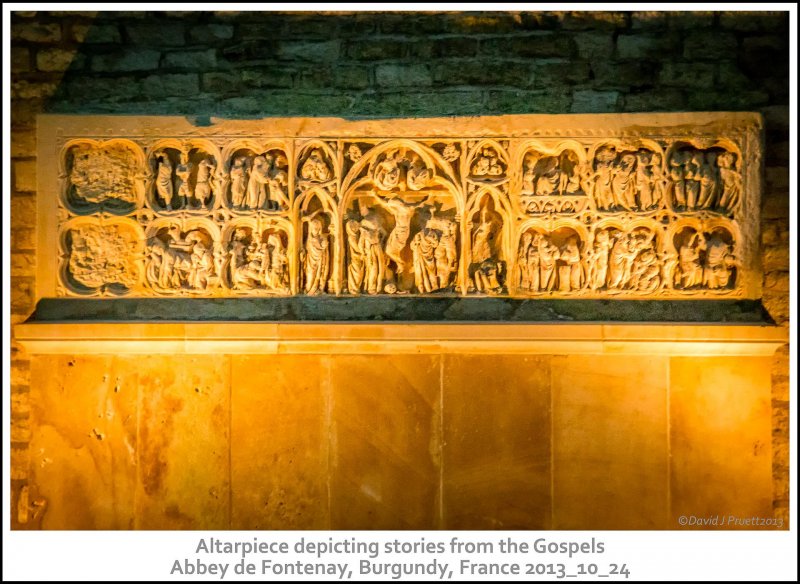

The most ornate item in the church was the altarpiece. It was carved with stories from the gospel not as decoration, but as a tool for teaching and remembering.

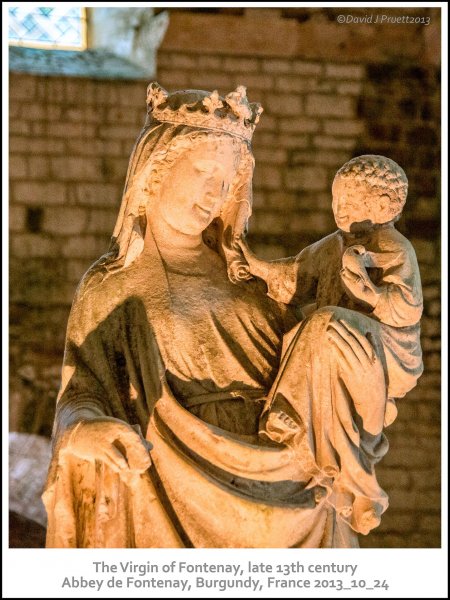

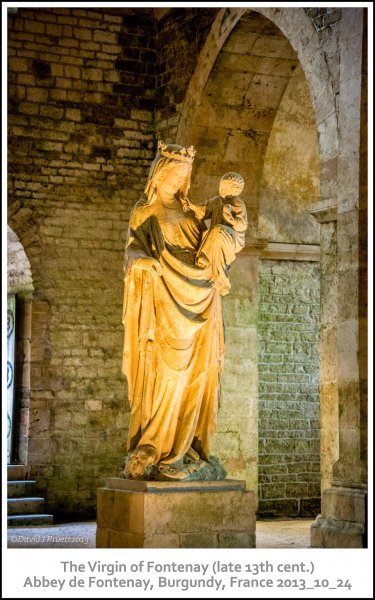

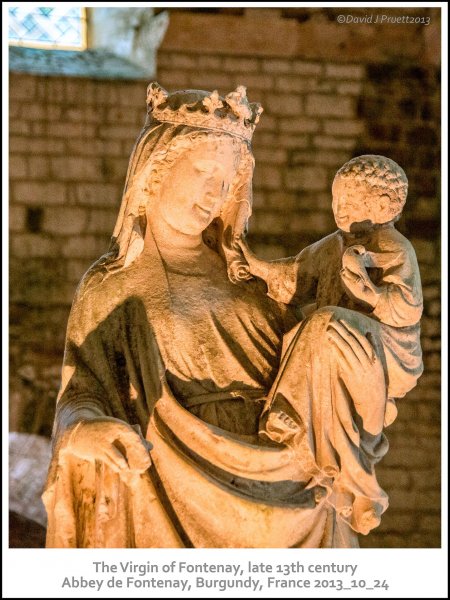

Bernard, like many Catholics through the centuries, was devoted to Mary, the Virgin Mother. The one piece of art in the church was a statue of the Madonna, Mary holding the Christ Child.

This is a priceless example of late 13th century Burgundian art. Mary is dressed in Burgundian robes and originally held a scepter in her right hand with the child on her left hip, closest to her heart. The statue remained in the church for over 600 years until it was sold during the French Revolution for the equivalent of about US$6 (5 €) in today’s currency. The family which bought the statue lived in the nearby village of Touillon, where it guarded the family tomb for over 100 years. In 1929 it was bought jointly by the owners of Fontenay and the French state to be placed back in its original home.

A closer look at the statue shows that, while a century of exposure to the elements took a toll, a great deal of detail is still visible. Her slight smile is typical of work from the Champagne region.

The church contains the tombs of several notables, including that of Ebrard of Arundel, Bishop of Norwich, who, as I explained above, fled to the Abbey in 1139 to escape persecution and who used his fortune to fund much of the early construction of the Abbey. Somehow I didn’t take a picture of his tomb.

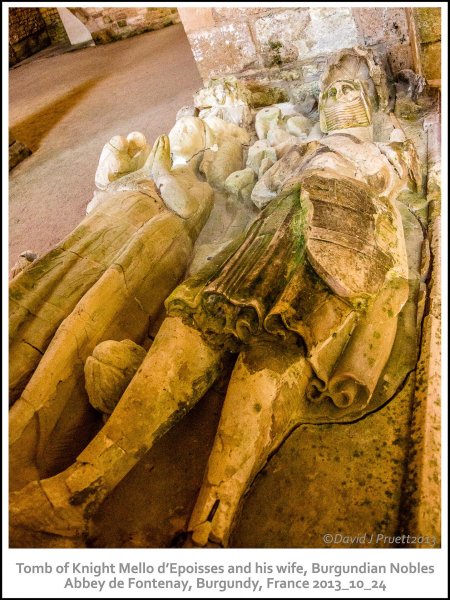

The most famous and ornate tomb is that of the knight Mello d’Epoisses and his wife, who were Burgundian nobles in the 14th century.

The knight is shown with his helmet on and dressed in full military regalia.

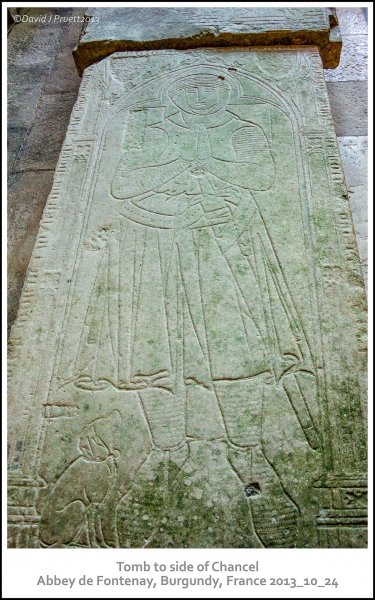

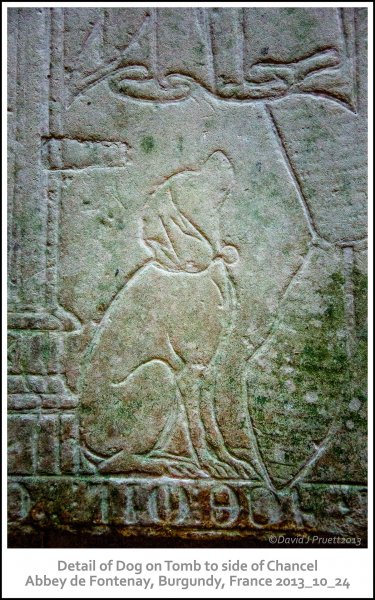

Another, much plainer, tomb that caught my eye was this one:

I was not able to find who was buried here, but the small, faithful dog in the lower left that made this one special to me.

At the chancel end of the church was a staircase known as the Night Stair. A common feature in monasteries, it led from the church directly up to the monks’ dormitory.

The Night Stair was needed when the monks were awakened two or three times during the dark hours for prayer. Traditionally, prayers were offered seven times a day based on a passage from Psalms “Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous laws.” Psalm 119:164 The hours of prayer were:

6:00 am – First Hour (Matins / Lauds / Orthros): St. Patrick’s Breastplate, and/or Psalm 5

9:00 am – Third Hour (Trece): The Lord’s Prayer

Noon – Sixth Hour (Sext): 23rd Psalm

3:00 pm – Ninth Hour (None): Psalm 117

6:00 pm (Vespers / Evensong): Psalm 150

9:00 pm (Compline): Instrument of Peace, and/or Psalm 4

Midnight: Psalm 119:621, Psalm 134

Each assigned time had a name as well as a theme, e.g., 9 am was called the Third Hour (Trece, in Latin) and the prayer would focus on The Lord’s Prayer from the New Testament.

Depending on the time of year and the schedule of particular a monastery, the monks would be awakened perhaps for the 9 pm prayers, certainly for the midnight prayers, and for the 6 am prayer that would mark the beginning of the day.

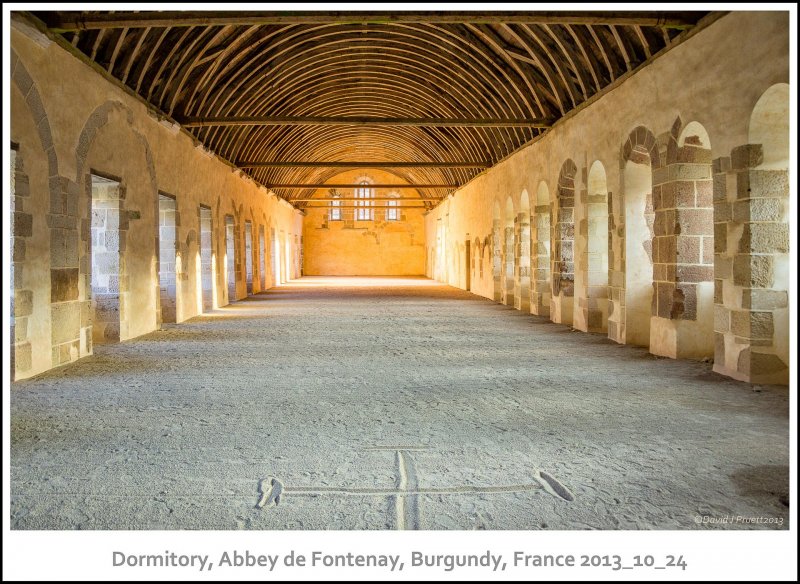

The picture of the dormitory above shows exactly how it was furnished, which is to say, it wasn’t. The monks would put a little straw on the floor, wrap themselves in a light blanket, and sleep in their clothes.

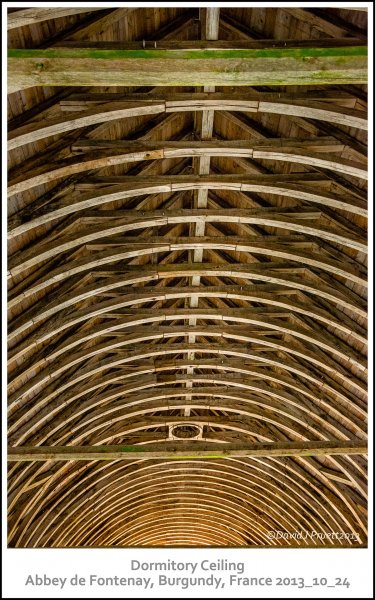

The ceiling of the dormitory is worth a closer look.

The timbers are made of chestnut that was shaped and then held in place with pegs. This is not the original ceiling, but it the one that was installed in the 16th century. I am certain that many 20th century roofs are in far worse condition than this one.

Below the dormitory are two rooms, the chapter house and the scriptorium. The monks met in the chapter house each day to discuss the agenda for the day and to study a chapter of the monastic rules laid down by St. Benedict, which was St. Bernard’s model for the Cistercians. The scriptorium, as the name implies, was where the clerks and the scribes among the monks would copy manuscripts and maintains the records of the monastery.

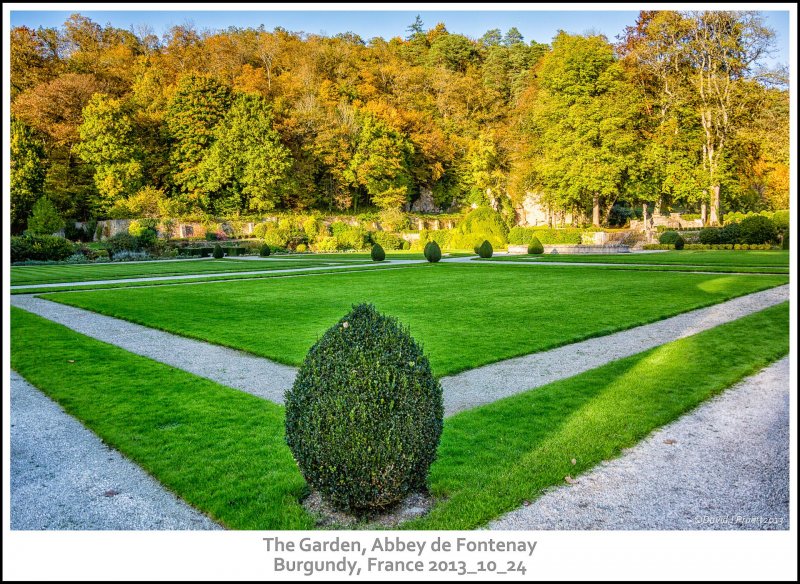

Looking out the windows of the dormitory, chapter house or scriptorium gave the monks a view of their main garden.

While this is the view today, it looked nothing like this in the 12th century. At that time, it was the garden used to grow almost all the food that kept the monks on this side of starvation. After World War II the gardens were redesigned to this classical arrangement that fits the lines and architecture of Fontenay well, but which have little to do with the original function of the area.

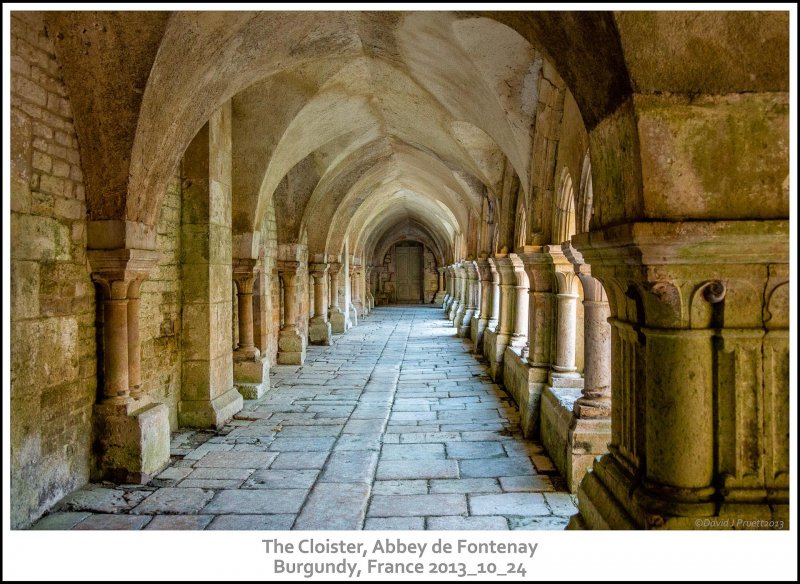

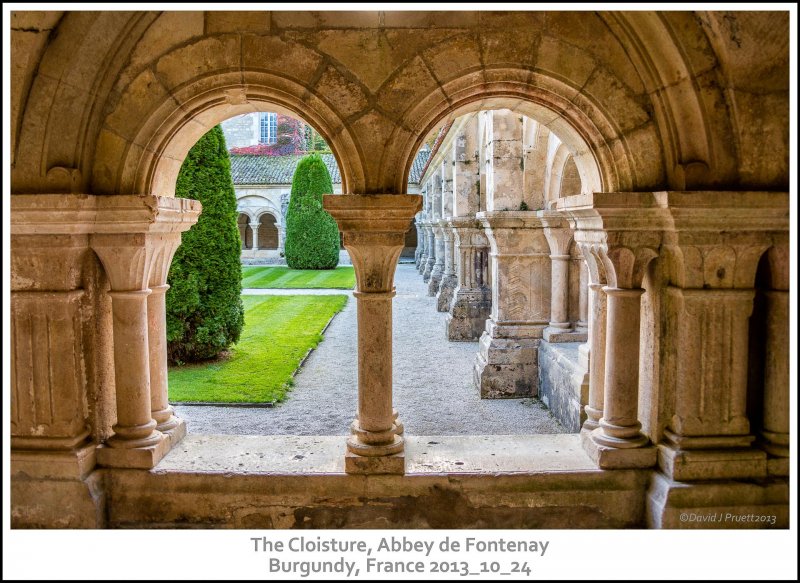

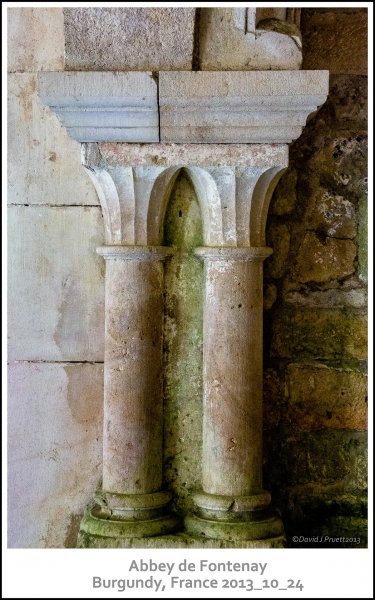

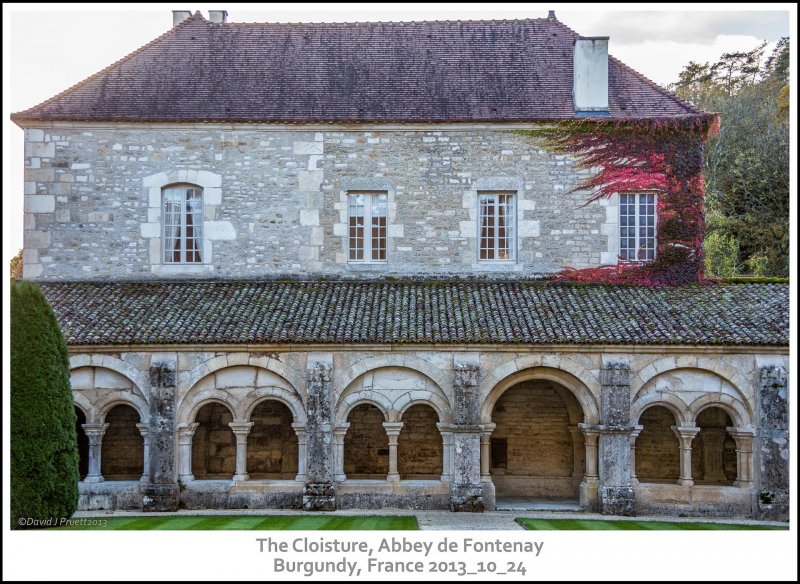

On the opposite side from the garden, the dormitory, chapter house and scriptorium were bordered by the Cloister.

This covered walkway enclosed another garden area and together they were used for walking, meditating and praying.

Notice how beautiful the stonework is in its simplicity. Ornamentation was minimal.

Here you can see the second floor of Abbot’s House, once side covered in ivy, looming over the cloister and garden.

One door and hallway passed between the charter house and the scriptorium and connected the cloister to the main working garden.

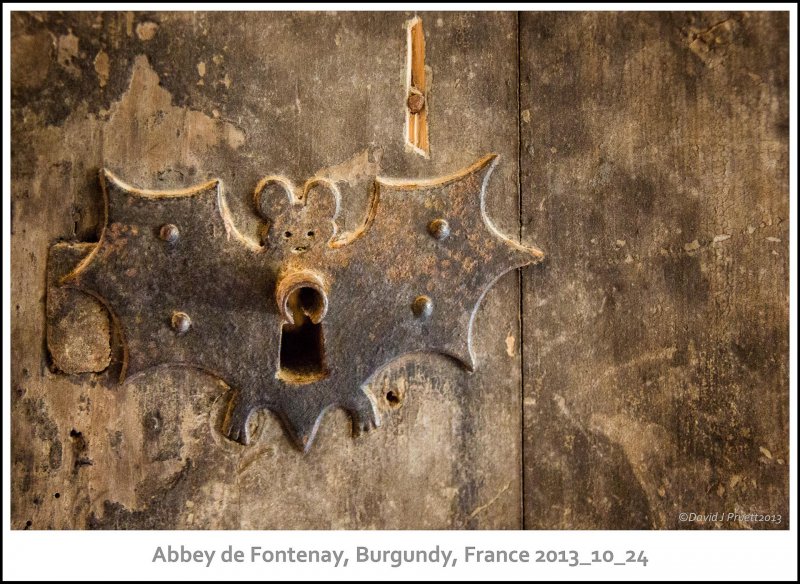

I was fascinated by one of the locks on one of the doors around the cloister.

I have no idea if this was a part of the original architecture, was added later, or is the earliest known version of the Bat Signal!

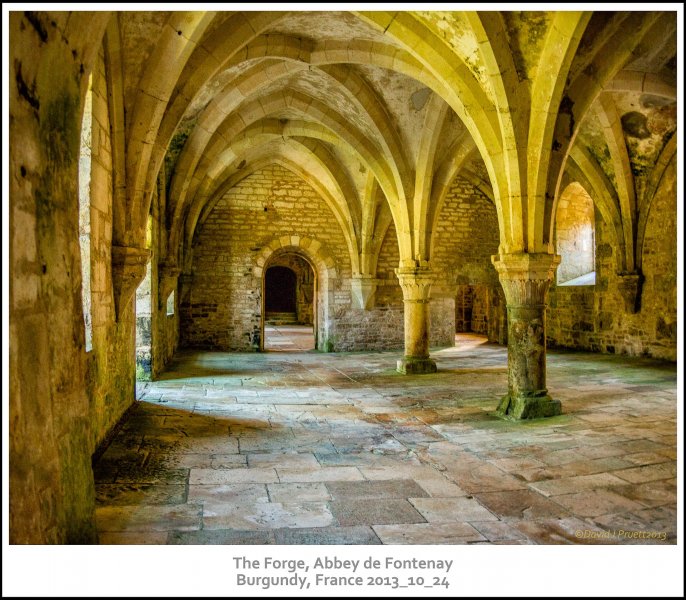

Continuing our clockwise tour of the grounds,we passed the infirmary, which is not open to the public, and came to the Forge.

The forge is believed to be one of the oldest metallurgical plants still in existence in Europe. It is over 165 ft (50 m) long. It likely held multiple furnaces like the one above, with large bellows to increase the heat of the fire. It also had several hydraulically powered hammer mills such as the one recently reconstructed.

These were powered by a waterwheel that has also been reconstructed.

A lot of space was available for material storage and work areas.

As we leave the forge and head back toward the entrance gate and the building there, we pass a fountain and pool (one corner of the forge is on the far left border of the picture).

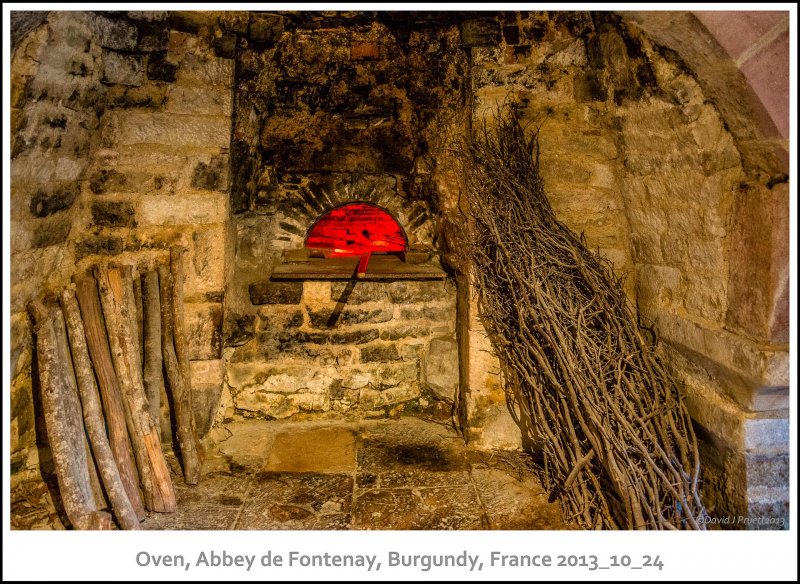

Finally returning to the buildings at the entrance, you can see the oven of the bakery with a red light to simulate fire.

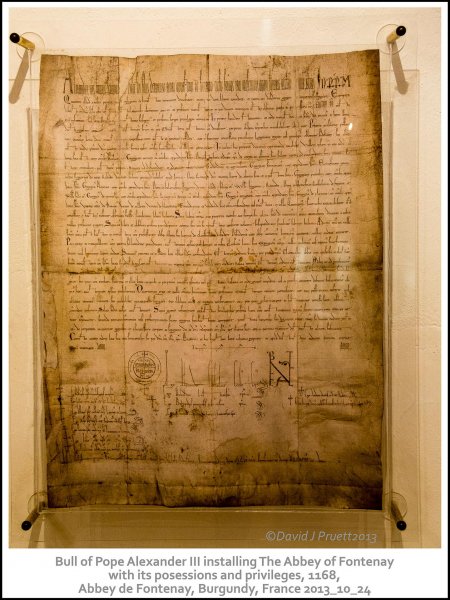

There is also a museum and gift shop that houses the original Papal Bull by which Pope Alexander III installed the Abbey of Fontenay as a monastery of the Roman Catholic Church.

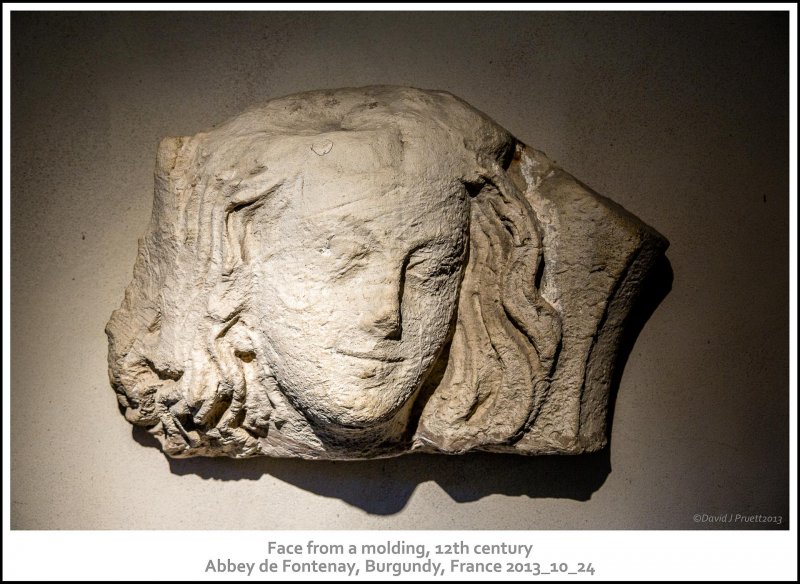

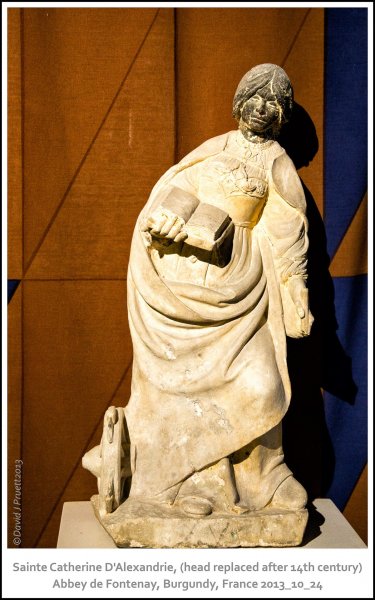

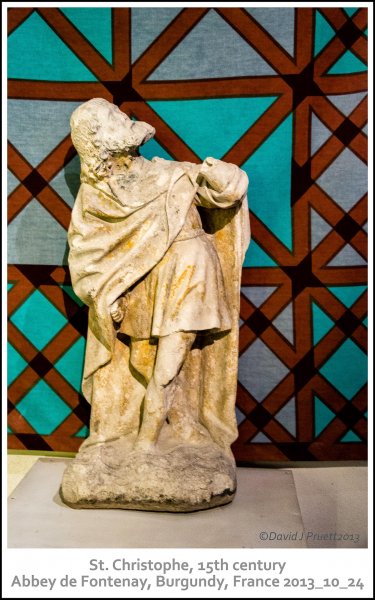

The museum also contains various architectural and cultural artifacts from across the centuries of the Abbey’s existence.

Finally, there is a model of the abbey complex to help you understand the layout.

The abbey of Fontenay is a UNESCO World Heritage Site for very good reasons. Rarely can you stand on the site and in the very buildings where people lived, worked and slept starting almost 900 years. The history of the abbey reflects much of the history of France and the Roman Catholic Church (and, therefore, Europe). To actually see and touch medieval architecture from the 12th century is an amazing experience. It was well worth the time we spent here.

So, this is my last entry chronicling our 5th, and next to last, day aboard La Belle Epoque. The next day would be a full one of sailing and touring, ending with the Captain’s farewell dinner. Stay tuned!

France

The author has no affiliation with any of the businesses, locations or products described in this article.

All images were taken with a Canon 5D Mark III camera and a Canon EF 24-105mm f/4 L IS USM Lens or a Tamron AF 28-300mm f/3.5-6.3 XR Di LD VC Aspherical (IF) Macro Zoom Lens (now discontinued; replaced by Tamron AFA010C700 28-300mm F/3.5-6.3 Di VC PZD Zoom Lens) using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.

THE SLIDE SHOW INCLUDES ADDITIONAL IMAGES NOT SHOWN IN THE TEXT ABOVE.