There’s a new restaurant in town that will almost certainly join the ranks of the Michelin-starred best. It’s named in homage to Baltimore and is quite a challenge to find even with a state-of-the-art GPS or map app. That restaurant is Oriole. We were there shortly after it opened, violating my general rule not to visit a new restaurant until it has had time to work out the kinks. It was a smart move. Let me take you through the menu and the experience.

Chef Noah Sandoval was last at the helm (or stove) of the one-Michelin star, gluten free Senza restaurant, which I wrote about two years ago. I had eaten there a couple of times before I even caught on to the fact that it was gluten free (perhaps because that is simply not an issue for me). Senza had a very casual atmosphere, almost like eating in someone’s home, but the food could have been served in a Parisian Temple of Gastronomy. I was sad to see them go, but happy to hear Chef Sandoval had plans for a new place, so I waited. And waited. My patience was rewarded.

At Oriole, Executive Chef Sandoval has teamed with Genie Kwon as his partner and Pastry Chef. Chef Kwon had previously created decadent desserts at Boka and GT Fish & Oyster Bar. Chef Sandoval’s wife, Cara Sandoval, runs the front of the house and will likely greet you at the door as you enter, much as she often did at Senza.

That is, of course, if you can find the door. Oriole is located at 661 W. Walnut Street. Walnut street would be better called “Walnut Alley” as it is only a block long, narrow, dark and complete with dumpsters. Our Über driver’s GPS and my iPhone told us we were there, but we did not see the restaurant (marked only by a small sign in the dark alley) until Ms. Sandoval came out and waved to us. I suspect they must always be on the lookout for first-time visitors. Up a few stairs, through and inconspicuous door and you enter—a freight elevator! Yes, the entrance is a freight elevator. Not to worry. It’s locked open during restaurant hours and you pass through the open front and back doors to enter the beautifully decorated dining area with a full view of the open kitchen.

There are only 28 seats here. The tables, even tables for two, are larger than usual, which is nice. I don’t think there is any natural light (though it was already dark when we arrived and I might have missed a window). There are, however, a number of soft, warm lights that illuminate the restaurant and, thankfully, the tables. You do not have to read the menu, eat or try to take photographs in the dark. (All of my restaurant pictures are taken with whatever light is available.) Not that you have to spend a lot of time with the menu. There is one tasting menu with a dozen or so courses for $175. That alone limits the audience to a certain group of people who are willing to spend that much money on a meal, who are willing to let the chef choose each dish, and who want to spend a few hours at dinner. For me, this is heaven, but I realize that, for some people, it is more like hell. That’s why we have so many different restaurants with so many different price points, cuisines and vibes. Viva la difference!

I should mention that Oriole will, of course, do what they can to accommodate food allergies or special needs, but if you have very specific requirements for your diet (Kosher, vegan, gluten-free meal, anyone?) I’d check with any restaurant well in advance to make sure they can meet your needs.

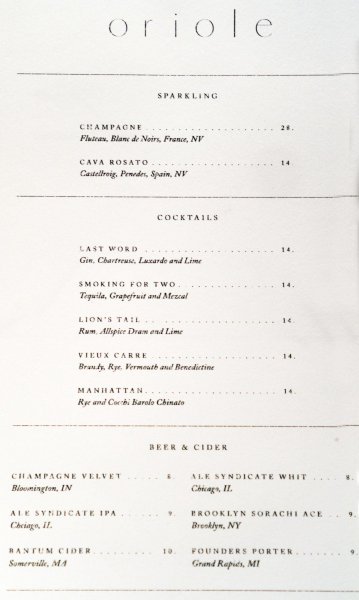

You can chose one of two beverage pairings: all wine ($125) or wine with beer, sake, etc. ($75). There is also a short cocktail and wine list curated by Sommelier Aaron McManus, who I had come to know and respect at L2O and Intro.

I chose (to no surprise at all to anyone who knows me) the wine pairings. However, we decided to have a drink before dinner so I ordered a Manhattan while Valeria went with her usual Champagne apéritif.

Oriole serves a classic Manhattan made with Bulleit Rye (a personal favorite) and a vermouth I did not know, Cocchi Barolo Chinato. I didn’t know it at time, but the Chianti would return at the end of my meal as a digestif.

Many of you will recognize Barolo as the king of red wines from Italy’s Piedmont region. It is made from 100% Nebbiolo grapes. Good ones stand proudly with the best Bordeaux, Burgundies, California Cabernets and Australian Shirazes as some of the greatest, most complex, longest-lived red wines in the world. Cocchi is an Italian wine company founded by Gulio Cocchi in 1891 that makes a wide range of wines, digestifs and apéritifs. But what is this Chinato stuff? Barolo made in China maybe? And while we’re asking questions, what, really, is the difference between an apéritif, a vermouth, and a digestif? The answer is, it’s complicated. You can, in fact, write a whole book on the subject and several people have.

I will keep it simple, since only wine geeks like me care anything at all about the dozens of styles and distinctions in these types of beverages. At its simplest, an apéritif is a beverage meant to stimulate your appetite before dinner. That means they are generally less sweet and have a lower alcohol content. Champagne and dry vermouth are classic examples. So is a Martini—the classic gin (or, if you absolutely must, vodka) and vermouth cocktail. The Martini was originally made with 2 parts gin and 1 part vermouth, which is abhorrent to many Martini drinkers today who want barely a breath of vermouth in their gin. (I’m not quite sure why they bother with the vermouth at all, but, to each his or her own.) Once stirred with ice, the classic was much lower in alcohol than a modern Martini and also served in smaller quantities, so it did work as an apéritif should.

Digestifs, as the name implies, are meant to be enjoyed after dinner and to aid digestion. They are generally sweeter and higher in alcohols than their pre-dinner counterparts. Familiar sweet liqueurs like Amaretto and Benedictine are examples, but so are Scotch whisky, Bourbon whiskey (both of which are used as apéritifs by some) and Cognac which are not sweet at all.

And what is a vermouth? It is, generally speaking, a fortified wine (i.e, extra alcohol has been added) flavored with a variety of herbs, botanicals, spices, etc. to give additional flavor and aroma to the wine. There are dozens of styles that can be red or white, bone dry to very sweet, extremely bitter, or not bitter at all. It is most often thought of as an apéritif, but some are enjoyed as a digestif as well.

Confused? You should be. There are just too many variations on these themes and the “rules” about when and how to drink them are, at best, rough guidelines. In the end, an apéritif is whatever you decide to drink before dinner, a digestif is whatever you decide to drink after dinner, and a vermouth is whatever comes in a bottle that is labeled vermouth. Don’t sweat it. Just enjoy.

OK, so back to this Chinato thing. Chinato (pronounced key-NOT-o) is not a reference to China, but to cinchona (or chinchona) which is the genus of plants that first gave us quinine, the bitter stuff used to flavor tonic water and fight malaria. Cecchi’s Barolo Chinato is a type of sweet red vermouth flavored with quinine bark (called china—pronounced key-na— in Italy) which makes it bitter, and a variety of other flavoring agents such as rhubarb root, star anise, citrus peel, gentian, fennel, juniper and cardamom seed. Since the base wine is a complex, wood-aged starting point to which still more flavor is added, the is a very complex vermouth. Or apéritif. Or digestif. Whatever.

I was happy to see a real Luxardo Maraschino cherry in the glass. These little flavor bombs are very different from the neon-red “cocktail cherries” you might used to.

Try them at home and demand them at your favorite bars and restaurants. Take a look at this video to learn more about how to make a Manhattan properly and why you don’t really want the neon-red cherries in your drink.

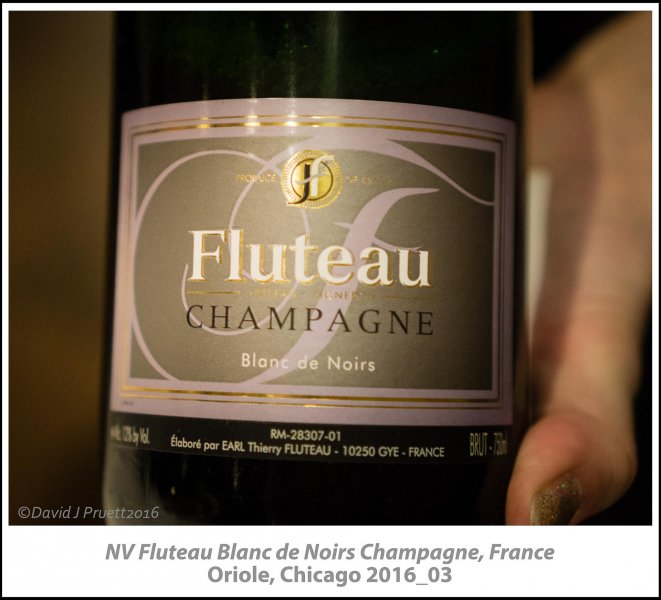

OK, let’s move on to the wine and food, shall we? While I’m making all this fuss about my Manhattan, Valeria has been sitting quietly sipping on her Champagne, the NV Fluteau Blanc de Noirs.

This was my first time tasting Fluteau Champagne, which served as Valeria’s apéritif and would also be the wine pairing with the first course. Not so long ago essentially all of the Champagne (real Champagne, capital “C”, from the region of the same name in France) in the United States came from a relatively small number of large Champagne houses. There has been quite a revolution in boutique Champagne production, however, and there is an ever-growing list of Champagnes from grower-producers available in the US and elsewhere.

Fluteau’s origin goes back to almost the moment the Aube region was recognized as part of Champagne in 1927. Alice Hérard, who’s father was a Champagne producer, married Georges Fluteau, who’s father was a wine trader. They decided to combine the two businesses and create Hérard and Fluteau, a négociant which produced Champagne from grapes purchased from local vineyards. Alice and Georges created Champagne Fluteau using grapes grown only on their 9 hectare (22 acre) property in 1935. They passed the business on to their son, Bernard, who, in 1996 passed it on to his son, Thierry.

Thierry Fluteau married a woman from Chicago (very cool to those of us who live in Chicago). You can read her story here. They have a son, Jeremy who joined the company in 2008 and is destined to be the 5th generation owner.

Here is a great map, courtesy of Wine Folly, that shows the areas in France where grapes for Champagne can be grown.

Aube is south and east of the main part of Champagne, very close to the northernmost part of Burgundy.

“Blanc de Noirs” means “white from black.” All Champagne is made from Chardonnay (a white grape), Pinot Noir and/or Pinot Meunier (two black grapes). With only a couple of relatively obscure exceptions, the color of grapes is all in the skin; the juice is clear. Red wine is made by letting the fermenting juice stay in contact with the skins. Press out the juice and remove the skins right away and you get white wine from black grapes—Blanc de Noir. This particular example is made from 100% Pinot Noir grown on the family estate.

Blanc de Noirs are often a bit heavier and fruitier than wines made with all Chardonnay (a Blanc de Blancs) or with a proportion of Chardonnay in the blend. This wine is very light and crisp and the aromas are more fresh apple and melon than the heavier yeasty or oaky notes often found in a Blanc de Noirs. I should note that these differences do not, in themselves, make a Champagne better or worse but are what allows a winemaker to create Champagnes in a variety of styles.

Fluteau Blanc de Blancs is, in my book, about as perfect an apéritif as you will find. Light, elegant, dry and floral with good bubbles and acidity it, will wake up your palate beautifully.

One of my pet peeves at a restaurant is to order an apéritif and then have the food and dinner wine show up on the table before the apéritif is half finished. That did not happen at Oriole. We had time to finish our drinks and then the first course was served: Osetra Caviar with Egg Yolk, Scallop and Cauliflower.

The Fluteau Champagne was perfect with this. Crisp, briny caviar, rich egg yolks, lightly seared scallop and cauliflower puree combined to give lots of subtle flavors and textures.

Another seafood dish came next: a Kusshi oyster with Iberico ham consommé, finger lime & mint.

A Kusshi™ oyster is a deep water, cultivated oyster from the the cold water between the British Columbia mainland and Vancouver Island. It was developed to be the perfect oyster with a consistently deep shell that allows for a plump, firm oyster and a smooth, strong, easy to open shell. The oysters are tumbled quite vigorously to smooth the shells before they are sold. Any good oyster would be well served in flavorful consommé of Iberico ham (more on that later) livened up with some finger lime and mint.

Finger lime is an Australian citrus fruit that was planted commercially in the US only a few years ago. It is sometimes called “the caviar of citrus.” If you look closely at the photograph, you can see some glistening yellow vesicles (the small juice-filled sacs that make up the flesh of citrus fruits) just to the right of the purple flower and below the green mint leaf; those are finger lime vesicles. The vesicles pop in your mouth and give a burst of flavor, like caviar eggs. (Very different flavors, of course!)

Our second wine was being poured about this time: the 2014 Antxiola, Getariako-Txakolin, Spain.

If this wine is familiar to you, you definitely have earned a PhD in wine geek. I had only had it once before in Barcelona, Spain in a tapas bar. That was some years ago and I had all but forgotten about it. The brand name of the wine is Antxiola (ahn-cho-la) and it is produced by Bodegas Zudugarai, a small, family-owned producer in the Basque region of Spain. The name is a reference to the old (built sometime before 1555), fortified house sketched on the label that can be found in the town of Orio, Spain not far from the vineyard where the grapes are grown. Getariako-Txakolin is the appellation, or geographic area, where the wine is produced. I had always meant to find this appellation on a map, but forgot all about it until now. Thanks once again to the folks at Wine Folly, here is a map that pinpoints the location of the region.

If you look at the very top of Spain, in the center beneath the right edge of the red banner you’ll see Bilbao. Just to the right of Bilbao is Getariako-Txakolin. Note that it is right next to the sea (the Bay of Biscay). Not surprisingly, the wines produced here go well with seafood.

Only two grapes are grown in this region: Hondarrabi Zuri and Hondarrabi Beltza, or Hondarrabi White and Hondarrabi Red. These are local grapes cultivated only in this region. Antxiola is typically made with 90-95% Hondarrabi Zuri with Hondarrabi Beltza making up the balance. It is a very light, citrusy wine with good acidity which, like the Fluteau Blanc de Noirs, is a nice apéritif or accompaniment to fresh seafood, especially shellfish. It is actually bottled with just a little CO2 (carbon dioxide) best known as bubbles in everything from water to beer to Champagne. This wine is not bubbly like that, but you get just a little carbonation that adds another layer of freshness on the palate.

Have you connected the dots here? Seafood—seaside wine—from Spain—Iberico (Spanish) ham. And the dots continue in the next dish: Iberico ham, with black walnut, mustard and campo de montalban.

If the wine had not already taken me back to that little tapas bar in Spain, this dish certainly would have. Jamón Ibérico is ham from the Iberian Peninsula, where Spain and Portugal are located. In virtually every tapas bar and many, if not most, restaurants, you will see a leg of Iberico ham on display, ready to be sliced and served.

Notice the black hoof at the end of the foot (upper right). Jamón Ibérico is made from a specific species of black pig that is native to the central and southwest part of the Iberian Peninsula, which includes parts of Spain and Portugal. The very best are allowed range free in oak groves and feed on bellota (acorns). After the pigs are slaughtered, the legs are salted and hung to dry for two years or more at the highest quality levels. The result is an intensely flavored, melt-in-your-mouth ham. True jamón Ibérico costs around $50 a pound ($110/kg), while jamón Ibérico de bellota can cost $100 or more per pound ($220+/kg), depending on the quality. You may find packaged slices of jamón Ibérico in your local grocery or gourmet store near the Italian prosciutto or American Smithfield hams. These are among the many types of hams from various locations around the world that are produced by a similar process. However, the different species of pigs, feed, climate and the choice to smoke the meat (or not), gives each one a distinct aroma and flavor profile. If you have around $900 to spend, you can order a whole leg of jamón Ibérico de bellota and impress your friends as you shave off paper-thin slices.

La Tienda (“The Store,” tienda.com) is an excellent source for a broad range of Spanish food and food-related products.

The bowl served at Oriole could easily have come from a tapas bar in Spain. (Tapas bars specialize in serving all kinds of small plates of appetizers and wines by the glass. Visit Emilio’s in Chicago or Hillside for a very authentic tapas bar experience.) Iberico ham with campo de montalban cheese, which is very similar to the better known Manchego, made from a blend of cow, sheep and goat milk. Black walnuts are more intensely flavored and harder to shell than the more common English walnuts. They are native to North America and, as far as I know, are not grown in Spain. I’m guessing they were included here as a nod to the flavor texture of the acorns that the pig fed on. A dollop of course-grain mustard and you have a delicious variation a classic dish.

Our next wine and food pairing would leave Spain far behind. We were off to Japan for Sea Urchin with yuzu kosho, ganmai & smoked soy.

From tapas to sushi without leaving the table. The impeccably fresh, delicious sea urchin (uni) was flavored with a dollop of yuzu kosho (a spicy chili paste made with fresh, spicy chilis and a Japanese citrus fruit named yuzu), ganmai (a herbal tea used in traditional medicine) and smoked soy sauce. Balancing all of these mild to very strong flavors is a bit of a trick, but they did it. One final touch: you can see some crispy toasted rice on top, so you had crispy rice on top, steamed rice in the maki roll below, and, as we shall see next, liquid rice to wash it down.

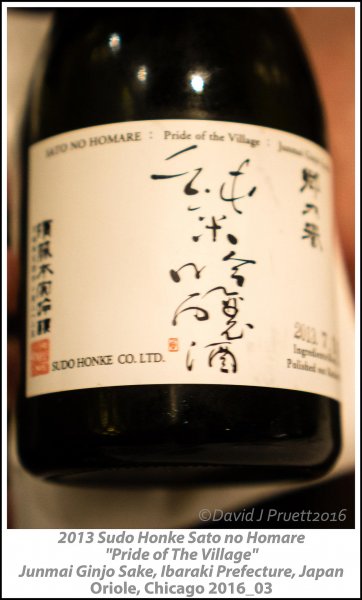

Sake would be an obvious choice to accompany this dish. Mr. McManus did not choose a generic version, but the 2013 Sudo Honke Sato no Homare “Pride of The Village” Junmai Ginjo Sake from Ibaraki Prefecture in Japan.

While sake is often referred to as “rice wine,” and there are certainly similarities between wine and sake, they are really two different beverages. Beer, too has some similarities to sake, but is also very different. Grapes, especially wine grapes, come preloaded from the vineyard with lots of sugar inside and usually a thin coating of yeast on the outside. In other words, a grape is a complete winemaking kit all on it’s own.

Rice, on the other hand, does not come from the field with yeast or sugar. At it’s milky white core, rice is starch, and yeast, the magic microorganism that changes sugar to alcohol, can’t work with starch. Enter a special microscopic fungus called koji. Koji is at the heart of much of what we think of as Japanese cuisine. Without it, there would be no soy sauce, miso, tofu or rice wine vinegar (mirin). And no sake. Koji converts starch to sugars which the yeast, in turn, converts to alcohol.

Of course, no one knew anything about what koji and yeast were back in 1146 when the Sudo Honke brewing company was established. It is currently run by the 55th generation of the Sudo family. (The oldest still-operating wineries in the world are Château de Goulaine, established c. 1000 in the Loire Valley in France and Barone Ricasoli, started in 1141 in Tuscany, Italy.) It says something about mankind’s ingenuity (or desire for alcohol) that koji and yeast were both discovered and controlled long before people had any idea what a microorganism was, let alone how it worked.

Sudo Honke is not only the oldest sake brewer in the world, it is one of the best. Rice must be polished to reveal the starchy interior for koji to work. The more it is polished, the more of the pure starchy core is exposed and, generally speaking, the higher the potential quality of the sake. Junmai is a type of sake that is made with only water, koji, yeast and rice that has been milled until only 30-70% of the grain remains. To be called Junmai Ginjo, the rice must all be milled to between 30 and 60% remaining. In fact, this sake was produced using 100% Yamada Nishiki rice, which was polished to 50% and so could be called Junmai Daiginjo, a higher grade. Sato no Homare means “Pride of the Village” and it is a terrific sake. Besides the floral, apple and pear notes that are common in sakes, there are hints of darker, red fruits on the nose.

Moving on, but still in seafood territory, Alaskan King Crab with cara cara, vidalia onions and oxalis came next.

The crab was perfectly cooked and served with a burst of citrus from cara cara oranges (a type off red-fleshed navel orange that is lower in acid and therefore tastes sweeter than other oranges) in a delicious vidalia onion broth. Somehow the flavors, including the delicate flavor of the crab, remained distinct even as they melded into a delicious dish.

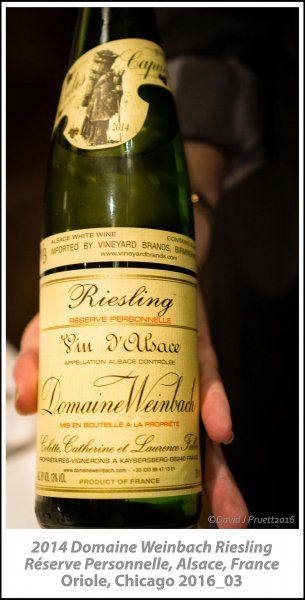

The wine was made from one of my favorite grapes from one of my favorite wine regions by one of my favorite producers: 2014 Domaine Weinbach Riesling Réserve Personnelle from Alsace, France.

Alsace sits on the border between France and Germany and, at various times, has been part of both countries. As a result, German names, foods and wine grapes are given French treatment and deliciousness results. Riesling is, arguably, the greatest white wine grape in the world. It can produce amazing wines in any style from bone-dry to very sweet and they can age for decades, not only staying fresh and drinkable but developing a remarkable range of flavors and aromas.

This 2014 offering from Domaine Weinbach, a consistently reliable producer in Alsace, was made with grapes from the famous the Clos des Capucins vineyard and fermented in large wooden casks. It is still very young, with a good acid backbone, some minerality, and the floral, apple-y nose of a young Riesling. As a side note, I have rarely found Italian Pinot Grigio to be very interesting, but the Pinot Gris (same grape, different name) from Alsace is generally much more flavorful and age worthy.

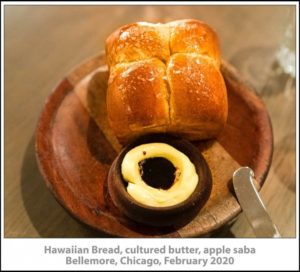

Another dish was brought out with this wine: Sourdough bread with cultured butter and local grains.

Sometimes simple is best, and what is simpler than bread and butter? Well, of course, there is a lot of bad bread and mediocre butter to be had. This was not that. The sourdough bread was complimented by the sweet, very buttery-flavored butter (made in-house), all topped off with the mild nutty favor of some toasted grains. A good wine, a plate of this bread and maybe a little cheese and you would have a delicious lunch or dinner.

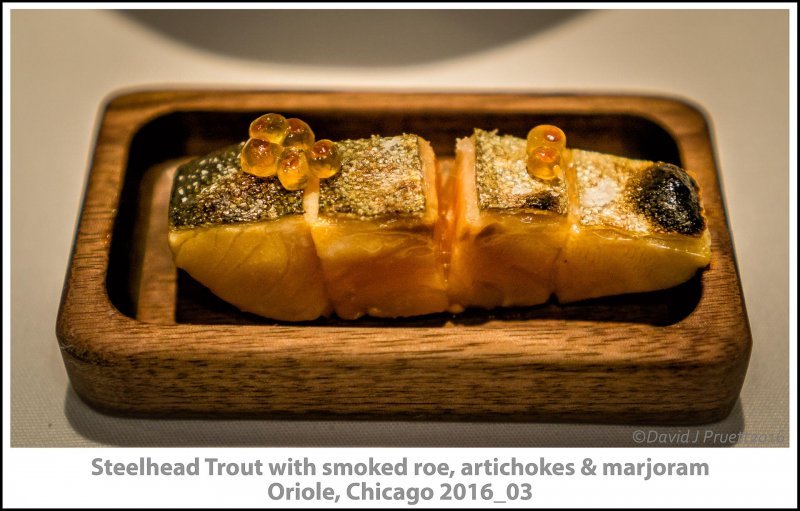

The next course have us a chance to play with our food a bit. In came in two parts, maybe three, depending on how you count. First, a bowl with some marjoram, smoke trout roe and artichokes.

A hot artichoke-marjoram broth was poured over this, while a piece of grilled steelhead trout was served on a separate plate.

We took a bite-size piece of trout and briefly dipped it in the bowl (so not to soak the crisp skin) before eating it. Tons of flavor and lots of textures, from silky-smooth trout to popping eggs to crisp skin. Yum.

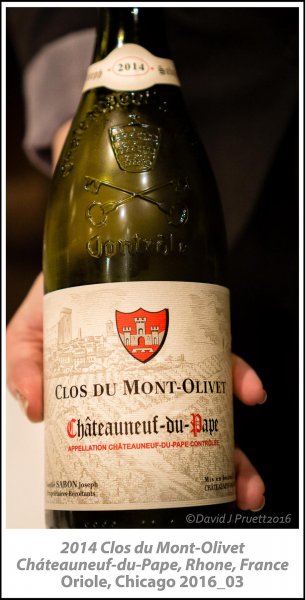

To wash this down, an unexpected wine: the 2014 Clos du Mont-Olivet, Cháteauneuf-du-Pape Blanc from the Rhone region in France.

I say the wine was unexpected because it is so easy to forget that white wines are produced in the Châteauneuf-du-Pape region. Over 90% of the wine made there is the often remarkable, Grenache-based (Grenache is a wine grape common in the Rhone region) red wine that most wine lovers know. But a small amount of what is generally excellent white wine it also made, mostly from Grenache Blanc blended with one or more of the 8 other white grapes that can be legally grown there. Clos du Mont-Olivet is a consistently good producer of both red and white Châteauneufs. This was a fairly full-bodied white wine that had a lot of floral and citrus aromas and flavors and a really bright acidity. Delicious.

The seafood courses were terrific, but I admit I don’t quite feel a meal is complete unless there is at least one red meat course. Chef Sandoval was ready for me.

Pork belly is everywhere these days, but lamb belly? Not so much. I used to see “breast of lamb” and “breast of veal” fairly regularly on menus, but I haven’t seen it in a while. I’m not sure why. Decline in the dominance of French cuisine? Maybe the world “breast” is considered sexist or micro-aggressive or otherwise politically incorrect? Anyway, whatever you call it, lamb belly, cooked properly, is delicious. It is a little tricker to cook than pork belly. Fat makes up a good deal of the belly (mine especially, but that’s a topic for a completely different blog). Pork fat is rather neutral in flavor, but lamb fat tends concentrate the lambiness (is that a word?) of the lamb and it can be too strong a flavor for many. Enter a chef who knows how to properly flavor and cook this particular cut. Coriander is a sadly neglected spice that is perfect with lamb belly. Anise hyssop is not just a beautiful purple flower that the bees love, but the leaves and the flowers have a wonderful anise flavor as well as a bit of sweetness. I’ve had teas made with anise hyssop and I understand it is used in folk medicine as well. Here it just added another layer or two of flavors to dish.

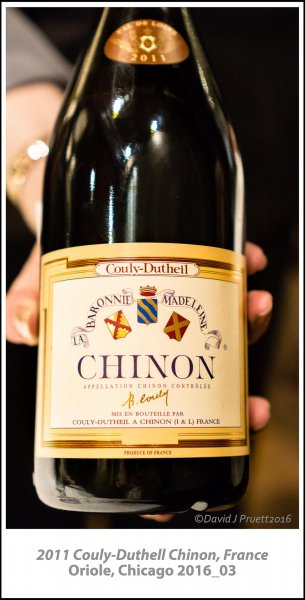

The rich fattiness of the dish called for a red wine to wash it down. Mr. McManus chose the 2011 Couly-Dutheil Chinon from the Loire Valley in France.

Chinon is a region in France’s Loire Valley. Most of the wines produced in the Loire are white and made from either Sauvignon Blanc (e.g., Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé) or Chenin Blanc (e.g., Vouvray). There are, however, a wide range of wines produced in the region, including reds, whites, rosés and sparkling wines produced from several wine varieties, including red grapes, such as Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir, and other white grapes, such as Chardonnay and Melon de Bourgogne. Chinon is best known for producing red wines from Cabernet Franc, which is used primarily as a blending grape with Cabernet Sauvignon in most wine regions (e.g., Bordeaux, California). However, in the specific soils and microclimates around Chinon, Cabernet Franc outdoes itself and produces delicious wines. They are generally somewhat lighter than a Bordeaux but can show quite complex aromas and flavors.

The 2011 Couly-Dutheil “La Baronnie Madeleine” is a perfect example. Domaine Couly-Dutheil was founded in 1921 by Baptiste Dutheil. René Couly married Dutheil’s daughter, Madeleine, and Couly-Dutheil was born. They own 90 hectares (222 acres) and purchase grapes from another 30 hectares (74 acres) of vineyards. In what they consider to be among their best vintages, they blend the most feminine barrels from all of their vineyards to produce “La Baronnie Madeleine,” named after the woman whose marriage created the family that is now a 4th generation owner. In the 2011 bottling there is a lot of ripe black fruit and hints of flowers (violets?) on the nose and this carried through in the flavors. A fairly big wine with good body, fruit and acidity that is fully ready to drink. Really nice with the lamb.

The next course was a meat course for vegetarians; no meat, but the delicious meatiness of black truffles.

This dish might be called “Fettuccine Alfredo on Steroids.” The yeast in the butter adds an extra dimension of, well, yeastiness and there is nothing quite like the aroma and flavor of thin truffle slices when they land on some hot pasta. The rye berries add a little more flavor and another textural element to a simple, but very sophisticated, dish.

This dish could be paired perfectly with any number of big whites or lighter reds. Mr. McManus chose a white, the 2012 Clos-du-Chateau de Puligny-Montrachet, from Burgundy, France.

Wine lovers (and regular readers of this blog) know that a white Burgundy is made with 100% Chardonnay grapes in the Bourgogne appellation. Bourgogne is the most generic designation for a wine from Burgundy, as it can be made with grapes from all over the region. This one is a little different, however. Château de Puligny-Montrachet is, in fact, a true Château, built in the 17th century. There is a small (4.5 hectares, or 11.1 acres), walled vineyard named Clos-du-Château (“Clos” refers to an enclosed vineyard in France) that is the source of the grapes for this wine. It is relatively inexpensive, retailing in the $20-30 range. Nevertheless, it shows some of the complex citrusy, mineraly complexity that the big (and much more expensive) Premier and Grand Cru Puligny-Montrachets are famous for.

A beef course came next in two parts: deep fried beef tendon and dry-aged ribeye steak sourced from Slagel Farms.

I’ve only had fried beef tendon a couple of times. It is sort of like pork rinds in texture with a mild beefy flavor. They could make a popular low-card snack food, but I suspect that isolating the tendons is pretty labor intensive and therefore cost prohibitive.

Many fine restaurants make an effort to source as many of their ingredients as possible from local producers. Slagel Farms is a family-owned business that specializes in meat from animals that have been raised naturally with no hormones, preservatives or other artificial additives. It is located about two hours southeast of Chicago and you will see the name on many menus in the Chicago area. I enjoy many of the great steakhouses in Chicago, where you can chow down on a pound or more of prime beef, but a menu like this one, which offers just a couple of bites of perfectly seared, meltingly tender, beef, allow you to savor the meat and still have plenty of room for all the delicious morsels that come before and after.

Mushrooms, onions and Béarnaise sauce are all classic accompaniments to a good steak, but the huckleberries were a nice surprise that added a touch tartness and sweetness to the plate.

I am happy that most nutritionists have removed butter from the black list and, depending on which report you want to believe, put in somewhere on the “neutral” to “good for you in moderation” lists. The classic butter-based French sauces like Hollandaise and Béarnaise still pack a pretty good caloric punch, but the intense flavored help a little go a long way. I cannot resist the opportunity to post this video of Julia Child and Jacques Pepin—two chefs who have inspired me since I was old enough to start cooking—making Béarnaise on the Martha Stewart show.

Not surprisingly, Jacques and Julia make it the classic way, which can be a bit labor intensive and tricky. There is a more modern method that can still be tricky, but is faster and easier.

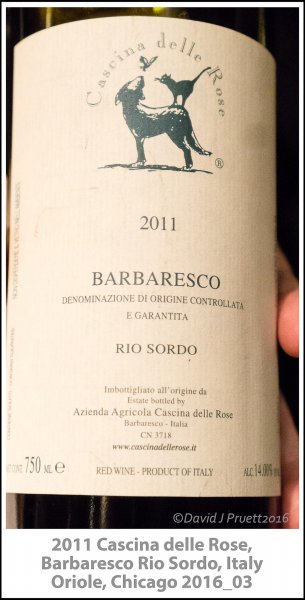

The rich, beefy flavors of this dish really calls for a big red wine. How about the 2011 Cascina delle Rose, Barbaresco Rio Sordo from Piedmont, Italy?

This wine, like the Barolo Chinato that was in my Manhattan at the start of the meal, is made from Nebbiolo grapes grown in the Piedmont region in Italy. Barbarescos, generally speaking, are a bit lighter and mature more quickly than Barolos, but they are still big wines that benefit from time in the bottle.

What else can we learn from the label? Casino delle Rose (“farm of the roses”) is a well-regarded producer of Barbaresco and Barbera (another grape grown in Piedmont and a rare case in Europe of the wine being named after the grape). Rio Sordo is one of their vineyards. This one was drinking beautifully at almost 5 years old. Lots of red fruit (especially cherry) on the nose and in the flavors, with complex floral, leather and earthy notes as well. Still young, but very ready to drink.

If you’d like to learn a little more (and enjoy some beautiful video footage) here is an excellently done, 10-minute video about Piedmont, but especially about the Barolo and Barbaresco wines.

The Wines of Barolo and Barbaresco from GuildSomm on Vimeo.

Anyone else have a sudden urge to go to Italy?

That ended the main portion of the meal, but there was one more savory course to enjoy, cheeses.

A mantra that Valeria and I repeat often is “we’ve never met a cheese we didn’t like.” We always enjoy a cheese course, even when we are getting pretty full from a big meal. The servings here are perfect; a small one-or-two bite portion of three very different cheeses.

Brunet is a soft Italian cheese made from pasteurized goat’s milk. Like the Barbaresco, it’s from Piedmont. It’s the white triangle sitting in the front left of the plate. It definitely has the tang of a goat’s milk cheese, but is creamy and smooth after aging in underground caves for a few months.

Mt. Tam is from the Cowgirl Creamery in Point Reyes Station in Marin County, not too far north of San Francisco along the beautiful Highway 1 drive. Cowgirl Creamery is owned and operated by cowgirls, or at least girls, or should I say women? Or ladies? Damn, it’s hard to know what is politically correct these days. Anyway, Sue Conley and Peggy Smith graduated from the University of Tennessee (for all my friends and former neighbors in Tennessee, Go Vols!) in 1976 and drove San Francisco together. They followed separate culinary careers until 1994, when they teamed up to start Cowgirl Creamery. They produce less than a dozen cheeses, several of them seasonal, from locally sourced, organic milk. It’s a great place to stop for lunch as you enjoy the redwoods and the Pacific coastline. Here are a few pictures from a visit a few years ago.

Invalid Displayed Gallery

As to the Mt. Tam cheese itself, it is a delicious triple cream cow’s milk cheese. It spreads and tastes like slightly nutty butter. Absolutely delicious even for those who only like very mild cheeses. It’s the wedge on the right hand side of the plate.

The third cheese, sort of hidden in the back in the picture, is Dorset from the Consider Bardwell Farm in West Pawlet, Vermont, so we’ve bounce all the way across the US from the West Coast to the East Coast. Like Cowgirl Creamery, Consider Bardwell Farm is a small, artisanal, creamery making cheese by hand in small batches with hormone and antibiotic free milk from local farms. They also make only a handful of styles, some only available seasonally. Dorset is a rind-washed, Jersey cow’s milk cheese. Rind-washed cheeses are literally washed with salt water (and sometimes other liquids, like wine) while they are aging. This promotes the growth of certain beneficial bacteria that give the cheese a funkier smell and complex flavors. This was certainly the strongest cheese of this trio, but it was by no means as strong as some of the really pungent, rind-washed “stinky cheeses” can be. We loved it.

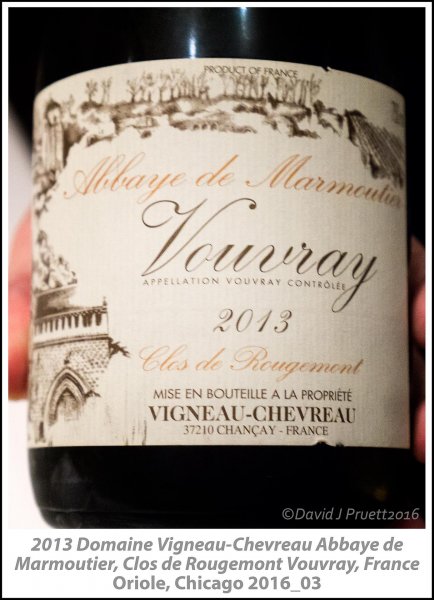

Valeria and I also agree that white wine is, in general, a better choice for cheeses than red. Apparently Mr. McManus agrees, as he served the 2013 Domaine Vigneau-Chevreau, Abbaye de Marmoutier, Clos de Rougemont from Vouvray, France.

Like the Chinon we had earlier, Vouvray is a region in the Loire Valley in France. For all intents and purposes, only white wine from the Chenin Blanc grape is made in Vouvray. Chenin Blanc was once grown extensively in California, but the wines were uninspiring at best. Its ancient home is the Loire Valley, where its high acidity and lively fruit flavors can work well in still or sparking, dry or sweet wines. (South Africa seems to be the only other place in the world where Chenin Blanc makes a particularly interesting wine in any quantity.) It is most commonly made as a dry white table wine that is delicious as an apéritif, with cheese, or with lighter fish and chicken dishes. The sweeter versions also work well with Asian food. Domaine Vigneau-Chevreau has been producing Chenin Blanc on their 69 acre (28 ha) farm since 1875. It has been farmed organically and biodynamically since the late 1990s.

In addition to the family farm, the Vigneau-Chevreau family was awarded a 50-year lease on the Clos de Rougemont, which is situated on the grounds of the historic Abbaye de Marmoutier, a Benedictine monastery founded sometime around 650 AD. It had fallen into complete disrepair by the end of World War II. In 1990, the Domaine Vigneau-Chevreau was granted the lease in exchange for restoring the vineyard, which they have done with excellent results. There is a lot of history behind this bottle of wine.

The next course, with Pastry Chef Kwon now stepping up and taking over, was just a touch of whimsy: pineapple sorbet with kaffir lime and coconut sealed in melted marshmallow on a stick.

Just a bit of fun before her more serious desserts (if dessert can be serious). To go with them, a serious wine, the 2009 Heinz Eifel Silvaner Beerenauslese from the Rheinhessen in Germany.

Most Beerenausleses from Germany are made from Riesling grapes. This wine, however, is not a Riesling, but a Silvaner (Sylvaner, Grüner Silvaner). Silvaner is a very old variety that is thought to have originated in Transylvania. It was once the most important grape in Germany, but now accounts for only about 7% of vineyards plantings. It can be used to make everything from very nondescript wine (oceans of it were used in cheap Liebfraumilch in the ’70s, which did nothing for the reputation of the grape or the wine) to very interesting wines that pick up a lot of character from the location they are grown in. This is one of the latter. A beerenauslese (literally “select harvest of berries”) is made, like the great Sauternes of Bordeaux, by picking individual grapes that have been left to shrivel up on the vine, usually infected with the “noble rot,” (French: pourriture noble; German: Edelfäule; scientific name: Botrytis cinerea) which sounds terrible but is, in fact, a most wonderful thing. It is a fungus that grows on the grapes and opens small holes in the skin to speed the evaporation of water and concentration of the juice. It also adds beautiful honey and peach aromas and flavors to the wine. The red “ba” on the label is a nod to how all the cool kids refer to beerenauslese: simply as “BA,” (pronounced by saying each letter “Bee A”) which is much easier (and faster) to say.

This is a sweet, honey and peach favored wine with enough acidity to balance the sugar. Great Riesling BAs are more concentrated and complex, but also prohibitively expensive. This was a very nice choice for, say, Gianduja Palette with banana, lemon & goat yogurt.

Gianduja is the ancestor of today’s popular Nutella spread. It was a blend of chocolate and hazelnuts invented in Turin, Italy, during the Napoleanic Regency (around 1800 AD) when chocolate was in short supply due to a British blockade. Hazelnut paste stretched the supply of chocolate and the flavors complement each other beautifully. The goat yogurt gave this dish a little extra tang and kept the sweetness under control.

Similarly, the next dessert, Chicory Custard with whiskey, cinnamon and Tahitian vanilla, was clearly a sweet course, but not so very sweet.

Chicory is a family of plants that have been used for centuries as a food and in folk medicine. Common chicory has spiky leaves and a blue flower. The roots are ground and used in the famous chicory coffee that is popular in Louisiana. Belgian Endive is another member of the family. Here it added a slight bitter note that balanced and played nicely with the sugar and wonderful flavors of whiskey, cinnamon and vanilla. If you are a fan of huge, mega-sweet desserts you would find these disappointing, but I loved the complex flavors and reasonable degree of sweetness.

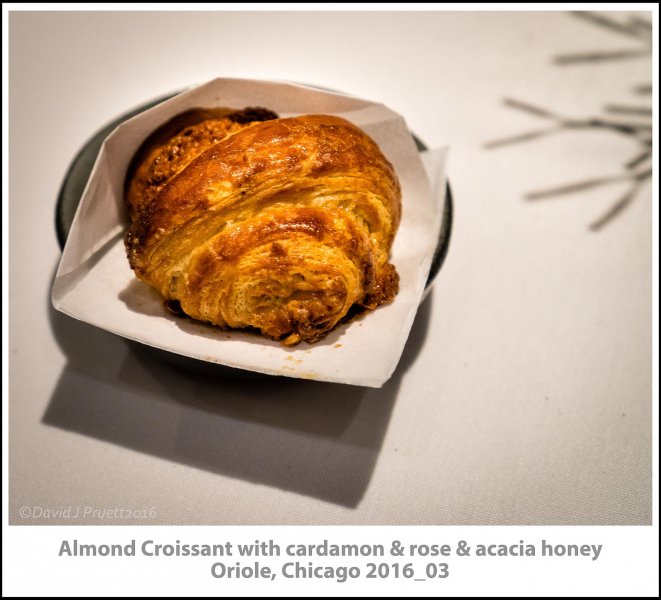

The final dessert was not one I would normally anticipate: an almond croissant with cardamon and rose & acacia honey.

This would be great for breakfast with tea and coffee and was just as good as a way to finish dinner. Valeria opted to go with tea, which came with a couple of small cookies as well.

However, I chose to finish with a look back to the way I started, with a glass of the Giulio Cocchi Barolo Chinato Cocchi. It was quite delicious all on it’s own. Sweet, bitter and with a wide range of flavors from the botanics, herbs and spices in the top-secret recipe.

From the moment we entered the not-so-easy to find door, this was a delightful experience from first to last. The ambience was warm and comfortable. The staff was friendly and knowledgeable. The food was outstanding and the wine pairings well chosen. As I said at the start, this is not a restaurant experience for every diner, but if you are the type who is happy to put yourself in the hands of the chefs and the sommelier for the evening, Oriole should definitely be on your short list.

Oriole

Address: 661 W. Walnut Street, Chicago, IL 60654

Phone: (312) 877-5339

Reservations: opentable.com

Website: http://www.oriolechicago.com/

Dress Code: Smart Casual

Price Range: $175 for fixed price menu

Hours: Dinner: Tuesday—Saturday, 5:30—9:30 PM

Credit Cards: AMEX, Discover, MasterCard, Visa

Chicago, IL 60521

The author has no affiliation with any of the businesses or products described in this article.

All images were taken with a Sony Alpha a6000 camera and a Sony-Zeiss SEL1670Z Vario-Tessar T E 16-70mm (24-105mm full frame equivalent) F/4 ZA OSS lens or Sony 35mm (52mm full frame equivalent) F/1.8 E-Mount Lens using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.