Noma. The Best Restaurant in the World. Not just once, but year after year. And it’s not in Paris or New York or Hong Kong or Tokyo. It’s in…Copenhagen. I have been to Copenhagen several times and love the city. However, as much as I love food, travel, Scandinavia, and high-end restaurants, it never crossed my mind to fly to Copenhagen just to eat at Noma. Besides the near-impossibility of getting a reservation, I have problems with the whole idea of declaring any restaurant to be “The Best in the World” (we’ll talk more about that later).

However, sometimes, as the old saying goes, it pays to have friends. If you are a photographer, you may know (or at least know of) Matt Granger (mattgranger.com). Australian by birth, photographer, teacher, and photographic adventure tour guide by vocation, I subscribed to his now extremely successful photography YouTube channel years ago. More recently, Valeria and I have joined him on photography-centric tours of Peru, Bhutan, Iceland, and Japan. We bonded with Matt (and, more recently, his wife, Kate) through shared interests—passions really—for photography and travel. Oh, and cats. We all love cats. And dogs.

Once we met in person, it didn’t take long for us to discover another shared passion: food. Matt has a newer YouTube channel called World’s Best Seafood. I’m not sure what the next level above “passion” is, but when it comes to seafood, Matt is at least one or two levels above passionate. The winter menu at Noma is all seafood, so Matt was determined to try it. He did not have much luck as an individual, but his YouTube channel is large enough to get him Media credentials, and Noma granted him a table for four in January. With only a very short window to accept or decline the reservation, Matt had to find two other people to fill the table. While he has many friends who have traveled with him and share his interest in food, only a few would be crazy enough to want to fly to Copenhagen in January to eat dinner. Fortunately for us, Valeria and I are that kind of crazy. When we got an email last September asking if we would like to purchase the other two seats, it took less than a minute for us to say yes.

Matt has already posted his video review of the experience, and here it is.

While there is, of course, overlap between the video and this post, you will find them complementary as Matt and I emphasize different aspects of the meal.

If you ever join Matt and me, separately or together, for dinner, this is what you will see for most of the night.

Does Noma live up to the hype. Let’s see. I’ll say up front that, in terms of the food and the hospitality, NOMA is second to no restaurant I know—and I know many! When you arrive, a greenhouse that doubles as a reception room is located right next to the street.

A staff member greets you as soon as you step out of your car and takes you inside. In addition to some of the plants that will find their way onto your plate later, there is a comfortable seating area where you can wait for all the members of your party to arrive. The staff offers you a warm beverage to enjoy while you wait. (I assume it’s a cold beverage in the summer.)

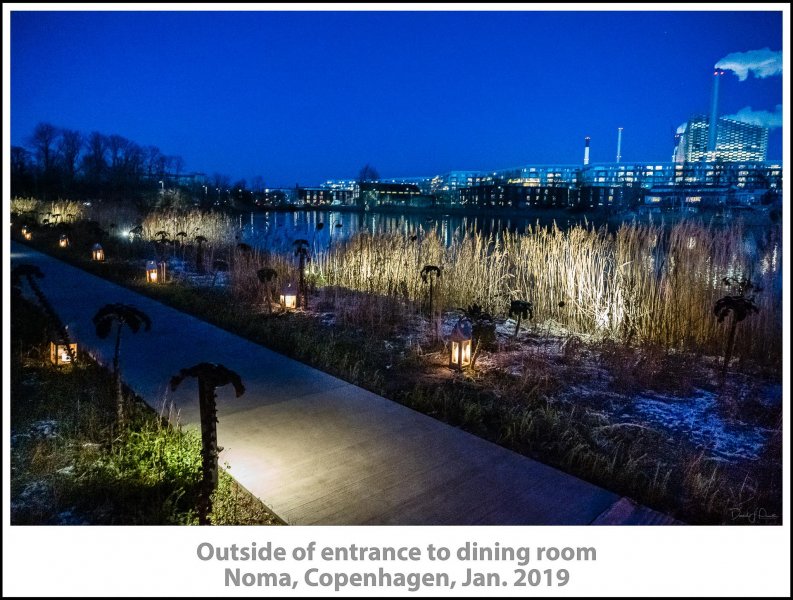

As soon as your whole party is together, you take a short stroll along the grounds of the farm/campus/restaurant complex.

The gardens are both decorative and functional. The defining concept of Noma—sourcing and using as many ingredients from Scandinavian land and water—begins right here as they grow and process as much as they can right on their own property. We’ll see just how well they execute this concept as we go through the meal.

When you arrive at the building where the main dining room is located, a cheerful fire just outside the door drives away some of the winter darkness and chill.

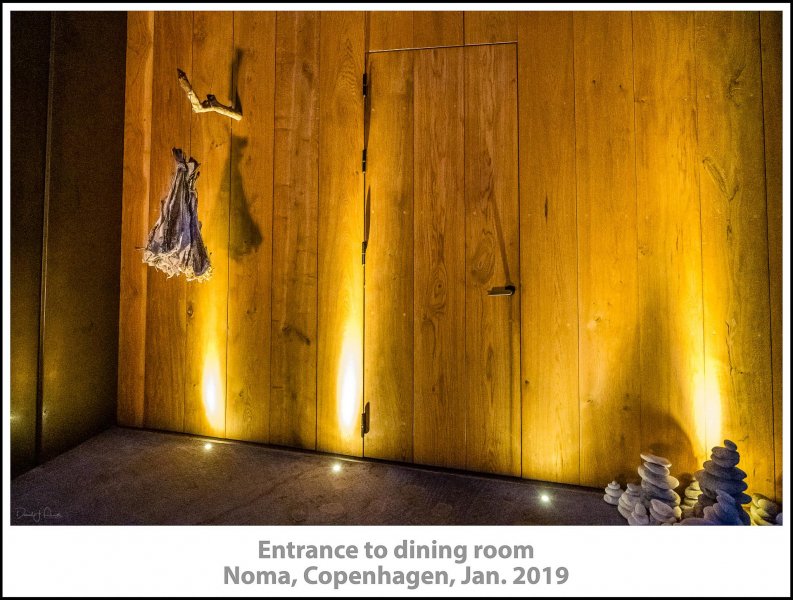

The entrance is, to say the least, unassuming. A plain (though beautifully crafted) wooden door in a wooden wall—very Scandinavian.

The dried cod hanging on the left foreshadows much of the meal to come. I’m not sure what the rock art on the right symbolizes; maybe the rocky Nordic shores?

The surprise as you walk in the door is a waiting group of every member of the kitchen staff that can stop whatever they are doing when a guest arrives and step over to the entrance.

This is called the “big hello” and every staff member, including the head man himself, chef and co-owner René Redzepi, will be there to greet you will a big “hi!,” “hello!,” “welcome!” They don’t just greet and run. They stand there as you check your coat and as you walk past them and the kitchen into the dining room. All the while they continue to smile, make eye contact, greet you, shake your hand, and, I am sure, pose for selfies if you asked. The open kitchen is positioned right next to the entranceway to make this sort of greeting possible.

The place settings are simple, earth toned, and probably made in Denmark.

The centerpiece was also simple and Scandinavian.

Candles are everywhere in the Nordic countries during the dark winter months. At certain times in the spring and summer you’ll see fields of blue wildflowers in bloom. I am not sure what species this was, but the warm light of the candle and the cheerful blue of the flowers were a nice combination.

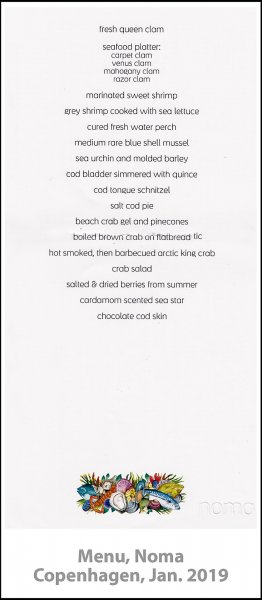

There is only one menu served each evening, so there are no decisions to make. Allergies and dietary restrictions are accommodated as much as possible, of course.

What makes the menu special? The (at the time) radical concept behind the cuisine at Noma was that it would feature, to the greatest extent possible, only ingredients from the Nordic countries, emphasize freshness and seasonality, and prepare the ingredients using both traditional and modern Scandinavian recipes and techniques. Chef Redzepi, Chef Claus Meyer, and other chefs in the region began formalizing these ideas around 2004, and Noma (short for NOrdisk MAd, which means “nordic food”) has remained at the forefront of this movement.

Contrast this with the menu at many fine dining restaurants that feature exotic ingredients from almost anywhere in the world, thanks to our modern ability to get almost any product from half way around the world literally overnight. Some like to debate the relative merits of these two approaches considering their environmental aspects, cost, cultural appropriation, etc. I will leave the political and social debates to other forums as this is not a social or political blog, but these concerns are worth discussing and understanding.

Today there is nothing unique about a restaurant that tries to source as many ingredients locally as possible. Charlie Trotter had local kids growing vegetables on vacant lots near his restaurant back in the 80s. “Farm to Table” is a catch phrase that appears on menus everywhere, but Noma has been a major influence on that trend, pushing the concept to new limits. Of course, that is relatively easy to do if you live in places like Southern California, a Caribbean island, southern Italy, or southeast Asia, where topical or semi-tropical conditions make for a year-round growing seasons. It gets harder as you go north or south from the equator into more temperate zones with shorter growing seasons. Historically, by the time you get as far north as Scandinavia, the land is not thought of as a source of many ingredients once the short growing season is over. The creative genius of Chef Redzepi and his staff at Noma has shown there are plenty of first-quality ingredients beyond cod, salmon, potatoes, and cloudberries that can be used to produce creative, delicious dishes all year.

For example, even in the dead of winter, when Scandinavia is covered in snow and ice, the sea provides an abundance of ingredients in what is really their peak season. Hence, the creation of the winter seafood menu that brought us here. It started like this:

You may never have seen a scallop served quite like this before. First, it is raw. Second, it is still alive; still attached to the shell and twitching. It was opened as we were coming in the door and served within minutes after we sat down. The pink-ish roe are scallop eggs, showing that this is a female scallop and further evidence that it is very fresh. (Roe deteriorates much more quickly than the body of the scallop.) The coral (as the roe is often called) is rarely seen in the United States, but is commonly served in areas where very fresh scallops are brought in from the sea alive and served promptly. It tastes pretty much the same as the scallop, but has a different, less firm texture.

Unless you dive for scallops yourself, or perhaps are standing on the dock waiting for the boat when it comes in, you will never taste a sweeter, more delicious scallop than this one. As a bonus, the shell is a natural work of art.

While the menu at Noma is set, you do have to choose between the alcoholic beverage pairing and the non-alcoholic beverage pairing. The non-alcoholic pairing is made up of a series of juices created in the kitchen using a wide range of fruits, vegetables, herbs and spices. I would have liked to have tasted those, but ordering both pairings would have been just a bit much.

The first pour for the alcoholic pairings was a beer brewed at a microbrewery in Copenhagen.

Regular readers know that I am not a beer drinker. I have tried very hard to learn to like it, but I just don’t. I wish I did, because good local beers are made almost everywhere in the world. Nevertheless, I am just as fascinated by the history and styles of beer as I am of wine, despite the fact I don’t particularly enjoy drinking them.

I had heard the name Gose (pronounced goes-uh) before, but knew nothing about it until I tasted it and later researched its history for this post. It is a style of beer developed over 1,000 years ago in Goslar, Germany. The groundwater around Goslar is slightly salty from the large salt deposits in the area. 1,000 years ago there were no water purification systems available, so you used the water you had. In addition, a little coriander was added during the brewing process to give some subtle, warm, floral notes to the beer. The finished product is a little sour, a little salty, a bit floral, dry, and refreshing. That is a very similar description to wines produced near the sea in, for example, northern Spain, that pair beautifully with seafood harvested there.

You won’t often find Gose style beers outside of Germany, so Noma and the Flying Couch Brewery of Copenhagen teamed up to produce this one. Here is the attention to detail and the commitment to using local products that Noma works so hard to achieve. Scandinavia will never be grape growing country (unless global warming really gets out of hand), but beer has a long history there. Their solution: brew a local beer with a style and flavor profile similar to the wines that traditional pair with seafood. Brilliant.

Did it make me a beer lover? No. I tried it, I appreciated what it was, but, for me, it was still beer.

Beer aficionados may wonder how a German beer can contain salt and coriander. Germany was the first country to lay down and enforce extremely strict rules about what could be used to make beer: water, barley, hops, and yeast—nothing else. These laws go back over 500 years, but they have been relaxed and amended to allow other styles of beer to be produced and to acknowledge historical styles such as Gose.

The first course set the tone for every course to follow: a specially brewed beer (or wine) matched to stunningly fresh and delicious seafood (which makes the Hamachi Crudo that seems to be on every menu these days look pretty lame). There you have Noma and New Nordic Cuisine in a nutshell: impeccably fresh, minimally processed ingredients from local waters paired with beverages made with the same philosophy and care.

I currently live in Chicago, possibly the steakhouse capital of the world. Virtually every high-end steakhouse offers a seafood platter, typically including raw oysters, steamed lobster, shrimp, and crab, as an appetizer. When all of the components are fresh and cooked (or left raw) properly, they make a fine starter for seafood lovers. At least that is what I used to think. The seafood platter at Noma takes the concept to a much higher level.

The last time I had a variety of clams like this in front of me I was in a small restaurant on the shore of the Pacific ocean in Chile. Carpet clams are a fairly widespread Atlantic species. Their grooved shells remind some people of carpets, hence the name. The sweet flavor of the clam meat married easily with the toasted grains (unspecified variety) and the sorrel added a nice, grassy brightness. Sorrel is a perennial herb that I have only recently seen used often in the US. There are a number of varieties that have citric, almost lemony notes that make it great with seafood.

Venus clams are a delicious species that were once very popular, but now compete with many other types for space in the kitchen. There are varieties many places in the world, but they are particularly delicious from the cold waters of the European coast.

There are several varieties of sea purslane, all of which are herbaceous, perennial plants usually found near the high water mark of ocean beaches. If you look closely at the Venus clam in the lower right of the image, you’ll see the thick, green, almost succulent-looking leaves standing between pieces of clam. It has a salty, herbal taste and is eaten raw, cooked, and pickled many places around the world.

Norwegian Mahogany clams, named for their beautiful, mahogany-colored shells, were also served simply with a little pool of fresh cream and some pine oil.

The fourth and final mollusk on the platter was a Norwegian razor clam, so named because it looks a lot like an old-fashioned straight razor. (See the image of the shells below.) The first three clams were all hard shell, which means they can be served raw or cooked. The razor clam is a soft shell clam, which is a reference to it’s thinner, more brittle shell, but, more importantly, soft shell clams have a longer siphon (basically their mouth or feeding tube, although it is sometimes called a foot) that prevent them from ever completely closing their shells. They always have to be cleaned and cooked before serving. These had been beautifully sliced and alternated with of hazelnut slices.

I don’t think hazelnuts grow as far north as Scandinavia (perhaps someone can correct me if I am wrong), but Japanese Quince shrubs do. The small fruits that grow on this plant are best harvested after the first frost, which softens the otherwise quite hard fruit. You can see a piece in the middle of the platter above. It looks a bit like a slice of green olive in the picture, but you can squeeze the juice out of it over the clams like a piece of lemon or lime.

Notice the care with which the clams are prepared and garnished. This is not just a bowl of clams with a little parsley sprinkled on top for color. Each clam has been carefully trimmed and sliced so that only the tenderest, most perfect bits are served, each with carefully selected garnishes to complement and enhance the flavor of the clams. While the first course could not have been simpler—open the scallop shell and serve—this course showed über-level skills at preparing and garnishing the clams. This would not be the last time we saw that level of skill.

A small bowl for the empty shells was thoughtfully provided on the side so we could admire just how beautiful they were.

Of course, a beverage was needed to wash these down. The 2016 Julien Guillot Cuvée Léandre “l’Homme Lion”, Mâcon Cruzille from the Burgundy region of France was chosen for that job.

I had never heard of Julien Guillot before this meal. It turns out the Guillot family has been producing wines in the Mâconnais region of Burgundy for three generations. Their vineyard, Clos des Vignes du Maynes, near Cruzille, was planted by monks at least as early as 910 AD. Let’s take a look at the wine map (courtesy of winefolly.com) to locate the vineyard.

I’ve written a lot about Burgundy over the years as it is one of the greatest (many argue the greatest) wine producing regions in the world. White Burgundies are produced from Chardonnay grapes while Red Burgundies are produced from Pinot Noir grapes (there are exceptions, but they’re not important here.) The northern end of the region, called the Côte d’Or and divided into the Côte de Nuits and the Côtes de Beaune, are home to some of the rarest, most expensive, dry red and white wines in the world. As you travel south through the Côte Chalonnaise and into the Mâconnais region, less red wine and more white wine is produced and the quality overall is less than the legendary wines from the north, but a lot of very good wines at much more affordable prices are produced.

The Guillot family started transitioning their vineyards to organic, biodynamic techniques in the early 1950s, way before either idea was cool. In fact, as far as can be determined, no pesticide, fertilizer, or other manufactured chemical has ever been spread on the vineyard. The current generation, lead by Julien Guillot, is a driving force in promoting organic and biodynamic wine production in all of France.

In addition to the main line of wines, Julien produces some very limited production (1 barrel) wines named in honor of his 2nd son, Léandre. These wines are aged longer and extremely hard to find, given the small production.

Perhaps you can see why there is a natural affinity between Noma and the Guillot family. Both emphasize using regional, traditional techniques and caring for local resources with minimal intervention in the wild, on the farm, or in the kitchen. Just as the chefs in Noma want the ingredients to speak for themselves, Guillot wants the grapes to express themselves and the ground they came from.

In that, Guillot is successful. The white Mâcon Cruzille is, of course, 100% Chardonnay. The nose has the flinty, mineral-driven nose that immediately suggests a wine from Burgundy. However, it does not have the freshness of wines produced using more modern techniques (whether organic and biodynamic or not). It is a good wine, but not on the same level as the food.

The next course, at first glance, looks like a couple of small, very red shrimp on a bed of seaweed.

Looking closer, you see that the “shell” is actually constructed from rose hips. Inside is the marinated shrimp meat and herbs.

My first thought was that the shrimp would be lost in the shell and the herbs. I was wrong. The sweet flavor of the shrimp came through beautifully. The textures and flavors played very nicely together in what has to be the most unique shrimp dish I have ever tasted.

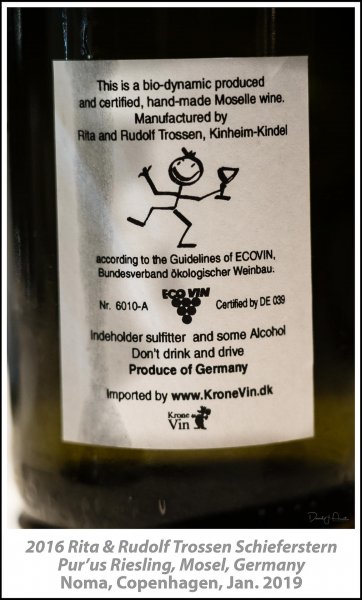

To wash down the shrimp, the alcoholic beverage pairing offered the 2016 Rita & Rudolf Trossen Schieferstern Pur’us Riesling from the Mosel region in Germany.

As we’ve discussed before, German wine labels can be complicated, but they offer a great deal of information about what is in the bottle. In addition to the year the grapes were harvested (2016), we can see they are Riesling grapes from the Schieferstern vineyard in the Mosel region. Erzeugerabfüllung translates to “estate bottled.” Landwein is a designation of the quality of the wine. In Germany, where grapes struggle to ripen in the relatively old northern region, quality is generally a reference to degree of ripeness. Landwein is one of the lowest designations, but it does not necessarily mean the wine was made from lesser quality (less ripe) grapes. Sometimes it just means the wine making process did not follow all of the rules needed to receive a higher classification, and that is the case here.

The wine is produced by Rita and Rudolf Trossen, who made a commitment to biodynamic winemaking techniques back in 1978, making them, like the Guillot family, pioneers in stopping the use of man-made fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides and relying on natural herbs and minerals to control pests and other problems in the vineyard. The Eco Vin logo indicates that they meet the strict German requirements to label the wines biodynamic. Pur’us is the term that have chosen to put on the label of their wines that meet these standards. They use no sulfites in any stage of the winemaking process. Only yeasts that naturally occur on the grapes are used and the wines are not filtered. They also leave the wine on the lees (bits of organic matter from the grapes and yeast that settle out after the wine ferments) for a long period of time. This is not too unusual for some styles of wine (e.g. some Chardonnays), but is unusual to Rieslings. Once again, it is clear why a wine made following this philosophy and production techniques was chosen to be featured at Noma.

Like the Guillot vineyard, the Trossen vineyards are ancient. The Romans planted grapes and made wine there.

German Rieslings have been a favorite of mine since I first began studying (and tasting) them back in the early 1980s. A great Riesling, with a good balance of fruit, sugar, and acidity, can age for many years while developing more and more complex aromas and flavors. This one was very young, but it was such a Riesling. In addition to the usual green apple and pear aromas and flavors, there was a certain hard to describe complexity and fullness from the extended time on the lees. I’d love to see how this one develops over the next 10-20 years, but these are small production wines that are very difficult to find in the US.

The next course could be called shrimp ravioli, except no pasta was involved.

The green “ravioli” wrapper is not spinach pasta, but an edible sea algae known as sea lettuce. Why sea lettuce? Well, it grows in the sea and looks and tastes a lot like lettuce. Except that it can become a very large lettuce. Left undisturbed in nutrient-rich water, the plants can grow to hundreds of feet long. It can be eaten raw in salads and is a great ingredient in soups and fish dishes.

Inside the wrapper were tiny Grey Shrimp. They are abundant in the North Sea and particular popular in Flemish cuisine, although I have seen them on many Scandinavian sandwiches and as a stuffing for tomatoes. However, I have to admit I am not such an expert on shrimp species that I can identify every small shrimp that is served to me, especially after it is peeled and cooked.

This was a tasty bite—and we were instructed to eat it in one bite. (Matt, ever the rebel, decided to inspect the interior, as you can see in his video review.) You could taste shrimp, salt and herbal notes. There was some crunch, but I am not sure if it came from the shrimp or the lettuce or both.

By now you won’t be surprised to learn that the wine served with this course was another minimally-manipulated wine made using traditional methods in small amounts.

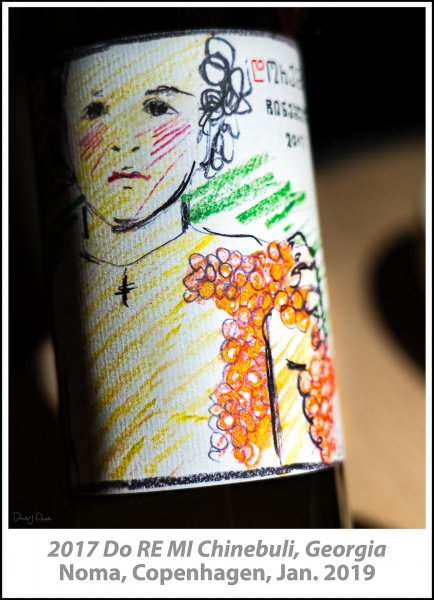

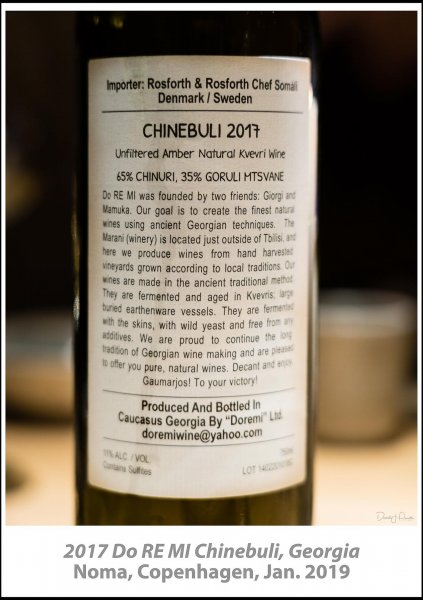

The 2017 Do RE MI Chinebuli is from Georgia, the country that was once a part of the Soviet Union, not the beautiful southern state in the USA. I am far from an authority on Georgian wines, but my wife, who was born in Russia, and her relatives have presented me with quite a number of bottles over the years, so I have studied them both academically and in a glass for a while now. I can only describe the ones I have tasted so far as “interesting,” which means I didn’t particularly care for them but it was interesting to explore the history and the the different flavor and aroma profiles the wines presented.

This, too, was an interesting wine. It is made from a blend of two grapes that you are unlikely to have heard of unless you, too, have studied Georgian wines: 65% Chinuri and 35% Goruli Mtsvane. Both are white wine grapes with a high acidity. Chiniuri, when bottled as a single varietal, is left on its skins for an extended period of time and takes on an orange color. Goruli Mtsvane is a light yellow-green.

The traditional Georgian method for making wine starts by lightly pressing the grapes and fermenting them with their skins, seeds, stems, and the wild yeast that comes with the grapes from the vineyards. This mixture is placed in large clay vessels called qvevri (or kvevri, spending on how you transliterate the Georgian world from the Cyrillic alphabet). These vessels, which look like Greek amphorae that you may have seen in museums or movies, typically hold between 1500 and 2500 liters (400 to 660 gallons), though they can be as small as 20 liters and as large as 10,000 or more. The kvevri are buried in the ground but left unsealed for several months while fermentation occurs. When cold winter temperatures kill the yeast, the clear wine is decanted from the settled solids (remember the lees described in discussing the German wine earlier?) into clean kvevri and sealed to age until spring. The solids (also called must or pomace) still contain a significant amount of liquid which is distilled into what the Georgians call chacha (unrelated to the dance of the same name, although if you drink enough of it you may think you can dance). This is the local form of what is called Brandy in many parts of the world, grappa in Italy, and so on.

The kvevri are opened in the spring with big parties and festivals much like the release of Beaujolais Nouveau in France in the fall.

How ancient is Georgian winemaking? Remnants of amphorae containing wine and grape residue have been found that date back to 6,000 B.C.

The Do RE MI (Do-Re-Mi, Doremi, etc. I see it spelled several ways. It’s Do Re Mi on the from label, Doremi on the back) marani (winery) was created in 2013 by by three friends named Giorgi Tsirgvava and Mamuka and Gabriel Tsiklauri. Like the Guillots in France and the Trossens in Germany, their goal was to produce natural, organic wines using traditional techniques—in this case, traditional Georgian techniques. If this wine is any indication, they know what they are doing. It had an orange, slightly brownish color which, if observed in wines from most winemaking regions, would be an indication that it was getting old. Not with these wines, however. It was young and fresh with some apple tartness, nuttiness, and some minerality. It was the best Georgian wine I have tried, though that is a low bar to get over.

Taking a one-course break from shellfish (the best of which is yet to come), the next course was freshwater perch.

When I was growing up in Michigan, perch was a common fish at fish fries. It’s still commonly served prepared in various ways at casual restaurants. I don’t think you will find it served raw, marinated in miso corn, and slathered with roasted kelp butter, however.

This was another dish that was amazing for its simplicity and depth of flavor. The perch was from a lake in northern Denmark. I have had, and even made, roasted corn on the cob dressed with miso butter. I should have asked more questions about how this one was made. I’m guessing that miso butter (just miso mixed with butter) was somehow infused with some corn flavor and used to marinate the fish. I thought I tasted some corn flavor while I ate, but was it there or did I just find it because of the description?

I have also had kelp (or seaweed) butter served with fish, but, as far as I can recall, it was always just raw seaweed combined with butter in a food processor to make a compound butter, much as is commonly done with all sorts of herbs and other flavorings. You can see the seaweed in the butter when it is done this way, but I don’t see it here. I suspect the roasted kelp was allowed to steep in some melted butter, then filtered off and the resulting golden-hued butter you see in the photograph was left to add a buttery, slightly herbal condiment to the fish.

Those are real pine skewers that the fish was served on, which added more aroma to the dish.

If you like mussels, the next course will spoil you for mussels prepared in any other way.

This mussel came in a bowl filled with seaweed and a seaweed-mushroom broth that smelled heavenly. It tasted that way, too, when we got to it. I am not sure how they got the caviar to stick to the shell this way, but it sure looked cool. The mussel was huge and plump and looked like it was coated in the same kelp butter as the perch had been, but the waiter did not mention it.

When I slurped the mussel and caviar, the salty pop of the eggs added texture to what was the most tender, delicate mussel I had ever tasted. Matt and the ladies had the same reaction. How did they make the mollusk so meltingly tender?

The answer was that it was not one whole mussel. It had been constructed by taking seven individual mussels and slicing off just the tenderest bit from each one, then reassembling the bits in one shell to look like a whole mussel. I am sure I will enjoy a big bowl of steamed mussels again one day, but I am also sure I will be dreaming of this masterpiece when I do.

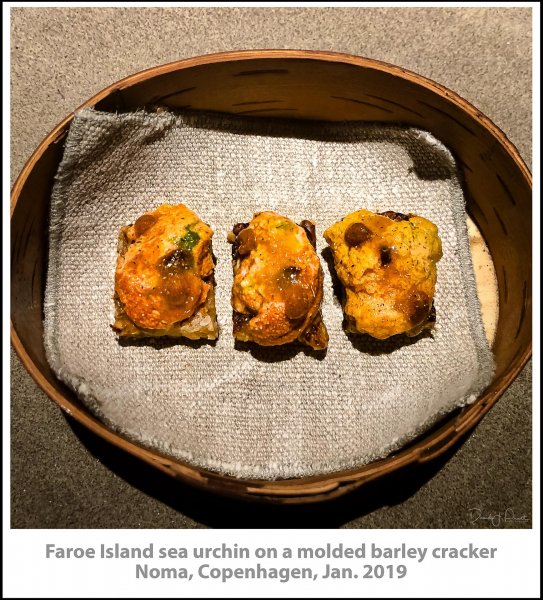

The next dish was “just” a little seafood on a cracker.

Sushi lovers everywhere know sea urchin (uni) well. High quality, fresh uni is a creamy, mildly favored delicacy. Lesser quality uni is, well, best left alone.

The Faroe Islands are a group of 18 islands in the North Sea about half way between Iceland and Norway. It is an independent country, but is also a part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

This was the first time I remember having seafood from the Faroe Islands (the second time would come later in the meal). Not surprisingly, it was delicious. The urchin was like butter.

Barley is an ancient grain not only in Scandinavia but in many countries. It is still one of the most used grains in the world both for food and for producing beer and other alcoholic beverages (Scotch, anyone?). At Noma, this very common grain was molded into a cracker, then made special by roasting it briefly over a wood fire. The flavors were subtle enough not to cover the uni, but definitive enough to enhance the dish to something above the ordinary.

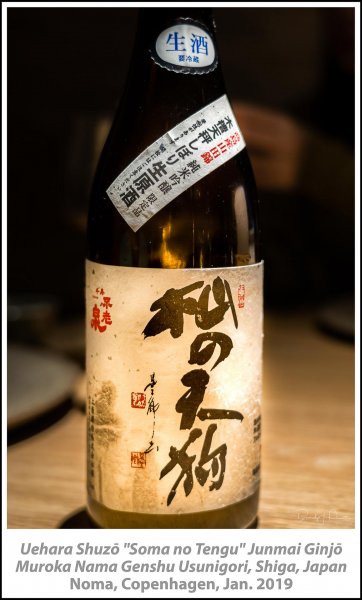

Appropriately for this “Nordic sushi” dish, a sake was poured to taste with it.

If there is anything more complicated than a German wine label, it’s a sake label. This one reads: Uehara Shuzō “Soma no Tengu” Junmai Ginjō Muroka Nama Genshu Usunigori, Shiga, Japan. Let’s see what we can learn from this.

Uehara Shuzō is the name of the producer. The name of this sake is Soma no Tengu, which means “Forest Spirit” in English. Junmai on a sake label means it is made using only rice, yeast, koji mold (a special mold that converts the starch in rice to sugar, which can then be fermented by the yeast), and water.

Junmai Ginjō means that the rice has been polished to remove the outer 40—60% of each grain. This is done to expose the core of the grain, which is closer to pure starch, and remove he outer parts of the grain, which can contain more oil, protein, and other components.

Muroka means there has been no charcoal filtration, nama means “unpasteurized,” and genshu means “undiluted” (i.e., no water added after fermentation).

Nigori on a sake label means “unfiltered” or “cloudy”—the sake has not been filtered by any method, so there are some small solids particles left over from the production process that remain in the liquid and make it somewhat cloudy rather than perfectly clear. Usunigori means “lightly clouded”—most of the solids are allowed to settle out of the sake before it is carefully decanted, but the finest particles remain in the liquid.

Shiga is the prefecture where Uehara Shuzō is located. The sake is made there using 100% local rice and water. Japan means—well, you know what Japan is.

There, wasn’t that easy? Don’t worry if you don’t remember all of these terms the next time you see a bottle of sake. If sake is your thing and you drink it a lot, you’ll remember them all eventually. If, like me, sake is an occasional indulgence and you don’t have a photographic memory, you might have to look up some of the terms again and again. That’s why we have smart phones and Google.

Consistent with Noma’s approach to all of the food and each beverage we have sampled so far, Uehara Shuzō is a family-owned (7th generation, founded in 1862) business. It is a small production brewery that uses traditional techniques to produce their sakes. They do not use any commercial yeast, but rely on the native yeast that lives in the winery to inoculate and ferment the sake. They use traditional wooden barrels (rather than modern stainless steel) during fermentation. A traditional wooden press (rather than a modern metal one) is used to slowly press the sake over a period of about 3 days rather than 12 hours.

All of this means the resulting product is more complex and has more body and mouth feel than a more, commercial, modern sake, even a high quality one. As with wine, filtration removes flavor along with solids. Unlike a wine, which is best carefully decanted off of any solid sediment that settles in the bottle, this sake should be shaken before serving as the fine solids left in it (“lightly clouded”) add to the texture of the drink. The nose had some citric notes lemon and orange) as well as the aroma of mushrooms or truffles, which I don’t think I have noticed in a sake before. It is very soft and smooth in the mouth. The particles left in the sake are far too small to feel, but they add body and texture. It seems to have some sweetness in the middle, but then finishes very dry. I don’t have the expertise in sake that I do in wine, but this one struck me as something special.

Near the beginning of this blog I noted the dried cod hanging by the door to the main kitchen and dining area and mentioned that it foreshadowed things to come. Those things started coming at this point in the meal.

If you eat fish at all, you have undoubtedly had cod. It is often served as a nice filet, sometimes breaded, possibly fried, baked or grilled. Salt cod has been a staple for centuries and is still served in the finest restaurants in various forms. As popular and common as cod is, I am willing to bet that only a small percentage of people have ever eaten a cod’s bladder, but that was our first cod dish.

I had never before seen a cod’s bladder, whole, sliced, raw, or cooked, so I had no point of reference on this one. Like the “mussel” we had earlier that has been carefully constructed from the very best bit sliced from numerous mussels, this dish was made up of layers of the cod bladder. Perhaps these were the best bits sliced from several bladders? I don’t know.

An aside here about the service at Noma. It is, quite simply, perfect. Professional, but friendly, informative, but without droning on for hours about how each individual dish is prepared. They tell you enough that you know what you are eating, but the food is left to speak for itself. Contrast this with some high-end restaurants where you might be told the name of the farm, the name often farmer, the name of the cow, and the name of the cow’s mother that your steak came from. Now, a foodie like me can be interested in all kinds of details of where the ingredients came from, how they were prepared, and why it was done just that way. Normal people, however, are happy just to know what is on the plate in broad terms and get after it. The staff at Noma can tell you as much detail as you like about each course if you ask, but their standard descriptions as they serve a plate are concise, but complete enough for most people.

All high-end restaurants are fussy about the ingredients they use and great skill goes into preparing and plating each dish. Noma takes this “fussiness” to levels I have not seen anywhere else. They have a lot to brag about, but they don’t. Non-foodies, just relax and enjoy without fear of boring lectures and boasting chefs.

Back to the cod bladder (not something I ever envisioned writing). You can see the skill that went into plating all the individual pieces and parts that make up the dish. The meat from the bladder was tender and, like many good fish, had a very mild flavor. It was supported by the flavor and texture of the fermented Japanese quince (Noma is famous for using fermentation and Chef Redzepi has literally written the book on the subject).

The gooseberries added color, texture and flavor as a garnish and in a sauce with mussels (maybe made with the bits of the mussel we didn’t eat in the reconstructed mussel dish?). Japanese quince, both fresh and fermented, added more flavor, all topped with the bright color and flavor of a slice of rose hip. Yet, for all the “stuff” on the plate, the flavors and textures were clear and clean, complementing, rather than masking, each other.

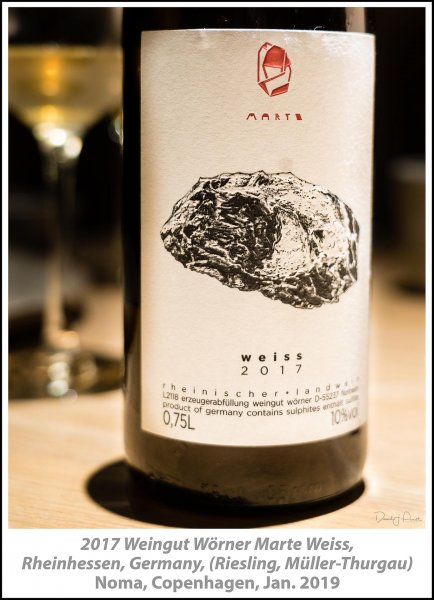

The wine for this course took us back to Germany, the 2017 Weingut Wörner Marte Weiss from the Rheinhessen region.

This wine was a blend of Riesling and Müller-Thurgau, so it is classified as a simple Landwein. Müller-Thurgau is a less well known grape variety that was developed in 1882 by a Swiss botanist named Hermann Müller. Müller was born in the Swiss Canton of Thurgau and referred to himself as Müller-Thurgau. When a man named August Dern took some of the vines to Germany and started planting them there, he named them Müller-Thurgau and the name stuck.

As we discussed earlier, Riesling is the grape used to produce the greatest German white wines. It has great aroma and flavor profiles and a strong acid backbone to make it refreshing and delicious when young with the ability to age and gain complexity for many years. However, it ripens late—sometimes too late—in the short German summer, so in some years it has to be picked before the fruit has ripened enough to fully balance the acidity. Silvaner is a white wine grape that ripens early, but is not very flavorful. Müller-Thurgau hoped to cross the two and get the aroma and acidity of Riesling with the early ripening of Silvaner. It seemed like a good idea, but it didn’t work, at least not completely. Müller-Thurgau grapes do ripen early, but they do not produce wines that are nearly as complex as a good Riesling.

Nevertheless, Müller-Thurgau was a successful variety because it would reliably ripen, give high yields, and produce a tasty, if not particularly fine, wine. Its high point was in the period between 1960 and 1990, when it was used to produce Liebfraumilch and Piesporter, two wildly popular, inexpensive, semi-sweet wines. As the taste of the global wine drinking public moved on to drier, more complex wines, the demand for Liebfraumilch and Piesporter, and hence Müller-Thurgau grapes, faded, many acres have been converted to other varieties, though it remains the second most planted variety in Germany.

Müller himself always referred to the grape as “Riesling X Silvaner 1.” As I turns out, however, it was not Silvaner than he used to produce the hybrid, but rather a similar grape called Madeleine Royale, which is quite similar. Nevertheless, you will still often see Müller-Thurgau called a cross between Riesling and Silvaner.

OK, enough wine geek stuff. What about the specific wine poured at Noma? You can probably already guess a great deal about the winery. Weingut Wörner is a family-owned, small production business. All vineyard management and production processes are as minimal and natural as possible. They use screw tops, rather than corks, to close their bottles. This may be non-traditional, but there are many (including me) who think that a screw top is a superior closure to cork, especially with wines that are not built to age for many years.

This was my favorite wine of the night. It is not a great wine built for the age’s, but it had a beautiful nose of tropical fruit and peaches. There was even a hint of peach color in the wine. The same tropical fruits came through in the flavor, along with some citric notes and solid acid backbone. I really enjoyed this one.

The next part of the cod to be served was the tongue, using a cod bone as a serving utensil.

If you are from Newfoundland, Norway and perhaps a few other places, you may have had fried cod tongue at some time. “Tongue” is really a misnomer, as it is actually more like the cod chin or throat (if a cod actually had a chin and a throat) though the tongue is still attached.

Here is a brief video clip showing the “tongue” being cut from the fish. (CAUTION: if you are squeamish about watching animals being cut up, skip this video.)

Traditionally, the small pieces are seasoned with salt and pepper, coated with flour, and fried. If a plate of them were offered to you and just described as “fried cod pieces” you would probably never know the difference. They are just a tasty piece of fried fish. I don’t know how the tongues were attached to the bones, but they were delicious. The wasabi flowers added fresh, herbal notes with a hint of wasabi spice.

Dried and salted cod (or just “salt cod”) has been a staple product for consumption and export in states bordering the North Atlantic for hundreds of years. It has been eaten for thousands of years, since fisherman began fishing, when salting was one of the very few preservation methods available. There are many traditional ways to prepare it, none like the dish served at Noma.

I’ll wager that Noma used true cod, likely line caught by small-scale fisherman. Regardless, as the dish approached the table, it looks like an empanada, the small, half-moon shaped pastry shells stuffed with anything from vegetables to fish to meat in many South American countries.

Appearances, however, can be very deceiving. What looked like a pastry shell at first glance turned out to be caramelized milk skin. If you have ever simmered milk on the stove, you have almost certainly seen the skin of coagulating proteins that forms on top. How the chefs at Noma managed to thicken this skin enough to collect it, caramelize it, and stuff it with salt cod is beyond my culinary imagination, but they did. The fish and the skin sort of melted together in my mouth, while the oyster leaf added texture and, yes, the flavor of an oyster. It was delicious.

About this time the 2008 Sébastien Riffault “Auksinis” Sancerre from the Loire Valley in France was poured.

The Sancerre region in the Loire Valley is best known for making crisp, clean, acidic and mineral-driven wines from the Sauvignon Blanc grape. They are beautiful with all sorts of shellfish and other seafood. As with the other wines we have discussed, this one is made by a small producer who uses biodynamic methods in the vineyard and traditional winemaking techniques to ferment and age his wines. Sébastien Riffault’s family has been growing grapes and making wine for generations in Sancerre. In 2004, Sébastien convinced his father, Etienne, to let him convert at least some of the vineyards to biodynamic horticulture and more traditional harvesting and vinification techniques. Those first experiments were successful and have been expanded to multiple vineyards.

Sébastien’s vineyards are now covered in a variety of plants, flowers, and grasses. No machines are used to plow the vineyards, only hand tools and horses. He has revived a practice that was once common in Sancerre, letting the grapes hang on the vines late in the fall until they are fully ripe and often infected with “noble rot” (a fungus called pourriture noble in French, Botrytis cinerea to scientists). The idea of rotten grapes may sound terrible if you don’t already know about it, but this special mold is what gives all of the great, enormously expensive, dessert wines of the world much of their unique aroma and flavor profile. Sébastien walks a fine line between grapes that are too overripe and botrytised to produce a good dry wine and catching the grapes at exactly the right point. He manages this by harvesting all grapes by hand, rejecting clusters and individual grapes that are over or under his specifications.

The grapes are then fermented in large, used, oak barrels that do not impart any flavor but also do not allow the same temperature control as modern stainless steel tanks. Fermentation is done by wild yeasts and the new wine is left to age on the lees (we talked about lees in the description of the 2016 Rita & Rudolf Trossen Schieferstern Pur’us Riesling earlier). It is bottled unfiltered and with no sulfur dioxide.

The result is a family of wines that are stylistically quite different from most Sancerre. I love Sancerre (and many wines made from the Sauvignon Blanc grape in France, Italy, the USA, Chile, New Zealand and more). Sancerre is the prototype Sauvignon Blanc, and is characteristically clean, crisp, light, steely, and flinty. Aromas and flavors vary considerably with where the grape is grown, but in Sancerre you often find grass, hay, quince, gooseberry, green apple, pear, and peach.

Riffault’s wines are heavier, darker colored, and I got more briny olive taste on this one than I ever remember in a Sancerre. Most Sancerres are best when young. They rarely age well beyond 5-10 years, though a few are built for longer aging. This one seemed to be a bit old to me, but I can’t be sure if it was the age or the winemaking technique. It was not a bad wine, but I didn’t love it. Was that because seeing “Sancerre” on the label set my expectations for a certain style of wine that Riffault does not make? I’ll probably never know as these wines are essentially unavailable in the US, so I am not likely to have a chance to taste the whole range over several vintages to appreciate the full scope of the winemaker’s efforts.

If my reaction to the wine was conflicted, my reaction to the next dish was clear: I loved it.

While there may be a lot of culinary magic that goes into this dish that I didn’t see, it seemed relatively straightforward. A rich crab stock, probably made with meat and shells, was jelled and served in the shell. The waiter identified the crab as Swedish. Pine cones, on the other hand, are not something I expect in a dish. Pine nuts, sure, but cones? As it turns out (and I didn’t know this going in), the unripe pine cones of the Noble Fir (one of my favorite Christmas trees) are edible. Chef Redzepi describes them this way: “They’re tender and edible at the moment. Sooooo delicious: sweet, citrusy and lots of pine. The texture is like biting into a succulent.” Check out his Twitter post for a video of him demonstrating how to use the cones. The little red triangles you see on the side of the dish are actually the young seeds from inside the cone. They added some herbal and, well, piney notes to the flavor of the dish.

The crab gel turned out to be just the “appetizer” for the crab portion of the menu. Danish Brown Crab appeared next.

Brown (or Stone) Crab are common and a popular food in Scandinavia. This dish harkened back to the crispy shrimp dish earlier in the menu (remember the shrimp shell made of rose hips?). Here a flatbread made using malt and beer was used to create an edible “crab shell.” The fresh crab meat is coming out of the shell, but inside is the goodies that come from the crab head. This was a clever way to package a part of the crab that is a delicacy to some, but unappetizing to others. It was delicious.

If I could only have one crab dish, it would have to be King Crab legs. Alaskan King Crab is wonderful, but King Crabs love cold, arctic waters around the world, including northern Scandinavia.

If you have taken a look at Matt Granger’s World’s Best Seafood channel, you know that its purpose, as the title implies, is to document seafood from all over the world looking for the best. Matt declared this dish to be the world’s best seafood—period—and wondered if he should just shut down the channel now. (Thankfully for us foodies, he did not.)

Why the hyperbole from a guy who, for example, is in Tokyo eating at the greatest sushi restaurants several times a year? Let’s look at the dish in detail.

I have already stated how much I like King Crab legs. I’ve had them dozens if not hundreds of times. These were certainly the best I have ever tasted. The legs need to be served simply, most commonly, at least in the US, steamed with some drawn butter on the side. Individual tastes vary, of course, and some like a squirt of lemon, a dusting of Old Bay seasoning, or even a horseradish and catsup-based cocktail sauce. To each his/her own, but, to my taste, less is more with this delicacy.

I love my smoker, but I had never considered smoking King Crab legs, thinking that the smoke would overwhelm the flavor of the crab. Grilling crab is also tricky, as it is easy to overcook. Somehow, the Wizards of Noma managed to smoke and grill the crab legs (Norwegian, in this case) just enough so that the meat was perfectly cooked, with just enough flavor from smoking and grilling to delicately complement the flavor of the meat. The horseradish milk was also brilliant. A normal horseradish sauce, whether creamy or catchup-based, would overwhelm the crab, at least to my taste. A few drops of the light horseradish milk was just the last bit of seasoning on a perfect dish.

The perfection included the way in which the shells were cleanly sliced so they could be lifted off like a lid to reveal the beautiful meat underneath.

I made some comments earlier about pretentious restaurants that take the farm-to-table concept to extremes. They have become a subject for comedians to joke about. “This steak comes from a cow named Bessie, who was named after her Grandmother, both of whom were raised by Farmer Sam Brown who has not left his farm since he was born there. Bessie was only milked by virgins to preserve the integrity of her meat. She ate only 100% organic grass, grown in a pasture that was blessed by a priest, a pastor, a rabbi and an imam. She was butchered by Pete the Butcher, who is Certified Humane and burns any small scraps of inedible material on an altar to the bovine gods.”

Having said that, Noma actually takes providing information about the crab a step farther, but in a way that seemed quite appropriate. It is not pretentious or showy, but discrete, high tech, and optional. As each crab is caught and processed, it is tagged with a barcode that accesses a database on information about that specific crab.

You might be able to read the code in the image above with your phone, but, if not, here is the link to “my” crab: http://nkc.no/track/?id=1401850. This may more than you ever wanted to know about a crab and a fisherman, but I think it’s pretty cool, much more fun than having a waiter talking for 10 minutes. It’s also optional—you can ignore it if you like, no harm done.

Oh, if you have questions about the freshness of your crab, it’s easy to verify. Just step through the kitchen (which we’ll do in a Behind the Scenes post on Noma) to an area with a series of water tanks where much of the seafood enjoyed in the menu is kept alive and well until dinner time.

Can you see the tag on the crab at the bottom of the tank?

While the legs are the star of the show, the rest of the crab was not wasted. The remaining edible bits were also smoked and served in a crab salad.

If they specified the greens in the salad, I missed it. Under them was a nice serving of crab meat that had been given a light bath in smoked butter. Another dish where, as far as I can tell, no special techniques were used, just impeccably fresh ingredients, treated gently, and served simply.

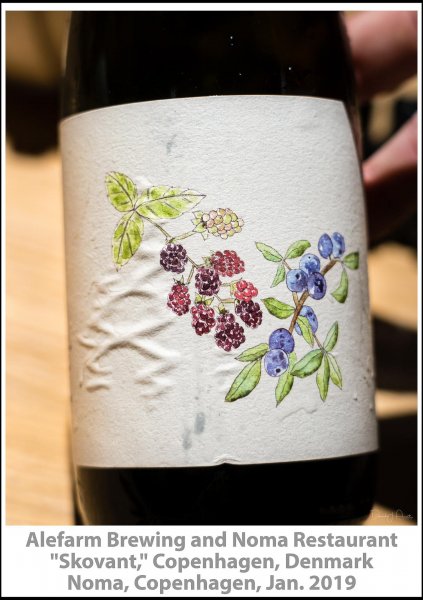

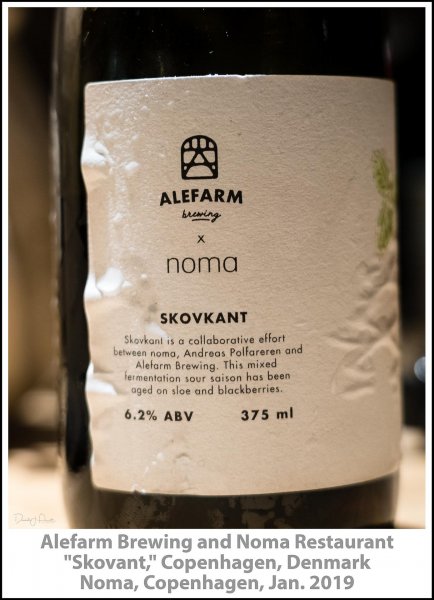

We end the beverage pairings as we began, with a unique beer, brewed for Noma by a local brewery, “Skovant,” by Alefarm Brewing and Noma Restaurant, Copenhagen, Denmark.

As I have mentioned, I am not a beer drinker so I wander in unfamiliar territory here. It appears that “saison” is a style of beer first brewed in the French-speaking part of Belgium. It was originally a pale ale, simply brewed with relatively low alcohol. Each farmer made his own in the spring and stored it to be consumed during the summer months by the field hands (saisonniers) that worked the farm and the harvest.

Modern saisons are more alcoholic (this one is 6.5%) and more highly carbonated that the original, country versions, and can be flavored in many ways with fruit, spices, herbs, and whatever else the brewer’s imagination comes up with. It is also a sour beer, which just means it has high acidity, which tastes sour (think lemons and limes). Skovant is aged over sloe berries and blackberries according to the label, but the waiter mentioned black currants and blueberries as well.

Alefarm Brewing is a small, family owned and operated (by Kasper Tidemann, and his wife, Britt van Slyck) craft brewery near Copenhagen. It was started in 2015. They produce a variety of seasonal beers in many styles as well as a lineup of year-round products. You recognize the template of a Noma partner by now: small, local, family run, using organic ingredients and natural techniques to create unique, high-quality products.

The beer looked very much like a sparkling rosé to this wine drinker, though, of course, it tasted nothing like that. I’ll leave it to the beer lovers of the world to judge the quality, but to me it was clean, crisp, with the sourness somewhat mitigated by the fruit flavors and aromas.

We moved finally to the last two formal (if “formal” is a word that can be used in the gracious casualness of Noma) course of the menu, the dessert courses. Perhaps not surprisingly, these are not spectacular, sugar and fat-filled sweets. Thankfully, they did not try to extend the seafood theme all the way to dessert. No fish ice cream or shrimp brownies. The first of the two courses was the only one that, as far as I can tell, makes no use of seafood in the recipe or in the appearance: Salted and dried summer berries with sheep’s milk yogurt and verbena.

Obviously you will not find much fresh, local fruit in Copenhagen that ripens in January. However, it is not necessary to fly in fresh fruit from half way around the world if you just do a little advanced planning, as was done for centuries before the era of the jet plane. Preserve some fruit in the summer by salting or drying, and all you need is a little water in the winter to bring it back to life. Yes, the flavors and textures are different, but still very good when the fruit is treated properly. Add some sheep’s milk yogurt tang and creaminess and a little verbena for herbal and lemony notes and you end up with a dessert that is as bright as a summer day.

The chefs at Noma have experimented with ways to serve starfish, but the experiments ended with the conclusion that some things are not palatable no matter how hard you try. So they made the next best thing: a starfish-shaped cookie.

Cardamom is a wonderfully warm spice, perfect in winter, and the very light coating of caramel on the bottom added just a touch of sweetness. The gooseberry powdered served to ground the cookie in Scandinavia and it looked very much at home served on a bed of seaweed.

At this point, menus are passed out, tours are given (see Part II of this series) and you can stop in the lounge for coffee, tea, a cocktail, or one last bite.

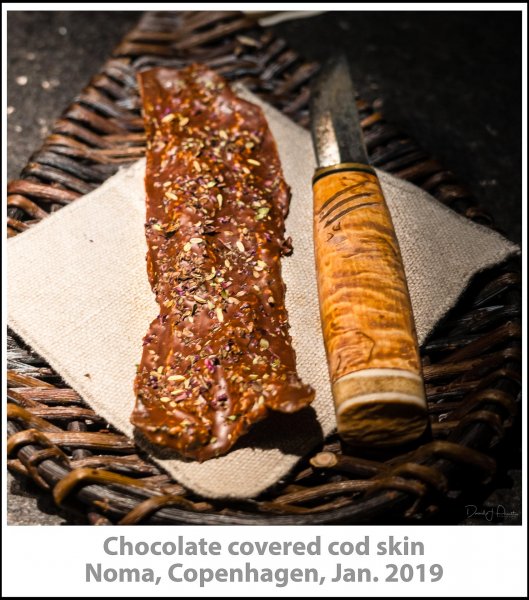

We’ve eaten the cod tongue and cod meat and used the bone as a serving utensil. About all that was left of the cod was it’s skin, which we will not waste.

Chocolate covered cod skin was a first for me. The flavors, at least what I got, were from the chocolate and the herbs and seeds on top, while the cod skin underneath provided crispy support.

I just had to see what Noma did with a cocktail, so I tried the whisky with seaweed kombucha and fennel.

It was nice, with a little smokiness from the whisky, licorice flavors from the fennel, a little salinity (from seaweed?) and the sweet/tart/sour flavors of kombucha.

There you have it, Noma’s winter seafood menu and alcoholic beverage pairing from first to last. It was a fabulous meal, complemented by a wonderful ambience, great hospitality, and beautiful ingredients treated with amazing skill.

So just one question remains: is Noma the Best Restaurant in the World? To me, that is a meaningless question. By what criteria can you make a meaningful comparison between every restaurant in the world? You simply can’t. Moreover, what is “best” to me may be “worst” to you. To take an extreme example: if you have a seafood allergy, this menu does not make Noma the best in the world, but the worst—it could literally kill you. What if you just don’t care that much for seafood, allergy or no? Or of you love Thai food? Or Mexican? Or Middle Eastern? Maybe you love seafood, but today you just happen to be in the mood for a ribeye steak.

The format is not for everyone, either: two or three hours of small plates. A thrilling experience for some (like me), a boring waste of time for others.

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants Academy is made up of 1000 people who are respected food critics and writers around the world. It’s a nice, multinational, multicultural idea: gather nominations for the best restaurants from every culture and country. It is definitely worth celebrating the food and restaurants found in places other than Paris, New York, and Tokyo because there are many other great food cities and great restaurants to be found in almost every country. Nevertheless, when you start with a ridiculous premise, that one restaurant is better than any other in the world, you get a meaningless result, no matter how skilled, knowledgeable and sincere the Academy members may be.

Having said all that, how good is the food and service at Noma? Very, very good. Superlative. They have a driving vision to create the best dishes that can be created with nordic ingredients, carefully sourced and prepared in innovative (which sometimes means bringing back ancient techniques) ways. They are wildly successful at this. The ingredients in every dish were impeccable and the preparation brilliant.

The ambiance and hospitality, too, equal or exceed anything I have ever experienced. The dining room is warm and comfortable with the open kitchen easily visible. Virtually the entire staff greets you as you enter. Each person who serves a dish or a beverage is friendly, gives a brief description of what is being served, and is ready to answer as many questions as you have in as much detail as you want, or to quietly walk away and let you eat.

For a foodie like me, who enjoys long, multi-course tasting menus with innovative ingredients and preparation techniques and long conversations with the staff about the details of what is on the plate, this place is heaven.

The only disappointment for me was the beverage pairings. They were good, even interesting, but the overall quality, to my palate, did not live up to the quality of the meal. Your mileage may vary.

This is not because they served two beers and I am not a beer drinker. I know that many people love good beer and many great restaurants include one or more in the beverage pairings. No problem. I also appreciate that Noma has clearly searched very hard for the most natural wines possible, featuring small, family producers that use organic, biodynamic, and traditional winemaking techniques. Even though I have been seriously drinking, studying, and seeking out wines from all over the world for 40 years, there are still untold thousands of styles that I have never tried. It’s always a treat when a sommelier offers a wine that was previously unknown to me.

Winemakers around the world are turning more and more to organic and biodynamic farming techniques and they are producing some amazing wines. I am not sure rejecting all modern winemaking techniques in favor of only traditional ones is a good idea. To be sure, its easy to overuse and abuse some modern technology (pesticides, herbicides, filtration, mechanical harvesting and handling), but some modern techniques (temperature controlled, stainless steel tanks) can be used to produce fresher, much more enjoyable wines—again, to my palate. Your taste may differ.

Contrasting the food and wine wines in the meal, every seafood dish was made with amazingly fresh (or skillfully preserved) ingredients, prepared to highlight the central elements. The results set new standards for seasonal, local cuisine that is being imitated around the world. It would not matter how local, organic, sustainable, biodynamic, etc., etc. the ingredients were if the food did not taste wonderful. The wines, in contrast, were fine, but not world class.

It would have been cool to see what is perhaps the most definitive Nordic alcoholic beverage included somewhere. Beer is, of course, a traditional beverage in Scandinavia that has been enjoyed since the first humans settled there, but it’s made in almost every country in the world.

If there is a drink that is more closely identified with Scandinavia than anywhere else, it is Aquavit (though it is popular in Germany as well). Norway, Denmark, and Sweden each take great pride in their national styles. Aquavit is distilled from grains or potatoes (in other words, it starts as vodka) and then is flavored with various herbs, spices, fruits, and other botanicals. The dominant flavor is usually caraway, but, depending on the particular bottle, there can be strong notes of anise, caraway, cardamom, cumin, dill, fennel, and citrus peel.

One of my most memorable meals was at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm one very cold, rainy, November day when going outside was just not an option. I am not a fan of buffet brunches, but alternatives were few and the food at the Grand Hotel was always outstanding, so we decided to go with it. The sommelier offered an aquavit, and I asked him if he could suggest several to pair with various items on the buffet. (I had only tasted a couple of aquavits prior to this, some 15 or more years ago.) As we made a few selections at each station—some focused on Swedish dishes, others on more international fare—our new friend took a look and poured an ounce or so of what he thought was an appropriate aquavit. I have long since forgotten the specific food and aquavits that I had, but I remember how much fun the experience, how different the aquavits were, and how well they paired with different foods.

There is probably a good reason why Noma doesn’t include an aquavit in their service. There are restaurants that won’t offer spirits of any kind as they feel the high alcohol content dulls the taste too much. I know of a couple of organic aquavits, but perhaps there are none that meet Noma’s model of small producer, organic and biodynamically grown raw materials, and so on. Both valid reasons and there may be others, but it still struck me as odd that the most Nordic of beverages didn’t show up all night.

In the end, however, none of my quibbles about the beverage selection outweigh the overall experience at Noma. The next time anyone asks us to help them fill a table there, we’ll be booking our flights.

Noma

Address: Refshalevej 96, 1432 Copenhagen K

Phone: +45 3296 3297 (Open Monday–Friday, 11:00 AM–16:00 PM)

Reservations: https://www.exploretock.com/noma

Website: https://noma.dk

Dress Code: Casual

Price Range: >$400

Hours: Tuesday – Friday, 5:00 PM–12:00 AM

Saturday 11:30 AM–7:00 PM

Credit Cards: Dankort, Visa, Visa Electron, MasterCard, EuroCard or American Express

1432 København, Denmark

The author is a member of the Amazon Affiliate program but otherwise has no affiliation with any of the businesses or products described in this article.

All images were taken with a Sony a7 III camera with a Sony FE 24-105mm F4 G OSS Standard Zoom Lens (SEL24105G) using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik Collection by DxO and Skylum® Luminar® plugins.

. .