There is a lot for a foodie to love in South America. The restaurants in Lima, Peru put it among the great culinary cities in the world. The wines produced in Chile are delicious and still, for the most part, reasonably priced. The restaurant scene in Santiago de Chile has also been improving steadily for a couple of decades now, and the little seaside restaurants along the coast continue to serve an amazing variety of mariscos y pescados (shellfish and fish) in humble surroundings. The Malbec grape has found a magical home in Argentina, where it is transformed into world-class wines that complement the meat and sausages, especially beef, that is expertly raised and prepared there.

The new Loews hotel in the heart of Streeterville in downtown Chicago is the home of a new Argentinean-style steakhouse by Iron Chef Jose Garces. Chef Garces was born and raised by Ecuadorian parents in Chicago, but he is best known in Philadelphia where he has no less than nine restaurants. Many Chicagoans know the one restaurant in town that has been part of the Garces Group for some years now, Mercat a la Planxa. Mercat is modeled after the wonderful tapas (small plate) bars in Spain; in this case, Catalonia Spain (Catalonia is the region in northeast Spain where Barcelona is located). If you enjoy tapas and Spanish wines, this is a place for you.

Rural Society is a completely different concept. The first one was opened in Washington DC, also in a Loews hotel, in 2014. The Chicago version opening in March of 2015. You can find some photos of the shiny new space in an article that appeared in Eater Chicago on opening day.

I ate there one lonely night about a year ago. Valeria was producing one of her Russian language cultural events and I was on my own. They seated me at a nice table in the large bar area. I ordered the tasting menu and came away with three impressions:

- The food was delicious

- There was enough food for 2

- It was very, very dark.

Now, it is not at all unusual for a restaurant to be dimly lit, but this was taken to an extreme. As I watched other diners come in, virtually everyone had to pull out a phone to shine some light on the menu in order to read it. Restaurants don’t light their tables for photography (nor should they), so I know that I will usually struggle to get decent pictures, but it was impossible to get a shot there even at f/1.8, 1/10 sec, ISO 25,600 (for non-photographers, those are the settings you might use to photograph a black cat in a coal mine). When I asked my waitress, who was charming and full of information about the food, how it was prepared, etc. why it was so dark she just mumbled something about “it’s the mood management wants”.

Did I mention that the food was plentiful and delicious? Despite the low light, I definitely wanted to go back. I got my chance when my friend Al was in town with his girlfriend, Debbie, and they wanted to try a new steakhouse. Valeria had also wanted to try the place, so we were a foursome. We were seated at a booth in the main dining area which, while still on the dark side, had enough light that I could get at least blog-quality pictures of the food.

As on my first visit, the staff was friendly and helpful. I have traveled in South America many times both for business and pleasure, so I am familiar with most of the items on the menu, but they will be new to many.

While Valeria has also made multiple trips through South America, our friends had not, so we opted for the tasting menu to get a good cross-section of the menu. While the tasting menu is described as having four courses, each course is actually several dishes, so there is plenty of food. At $75/person, it is a tremendous bargain for what you get.

While billed as a “modern Argentinean steakhouse,” the menu at Rural Society wanders across South America. Ironically, Argentinean steaks cannot legally be imported to the US, so the beef is from Uruguay (right next door to Argentina and very similar beef, but, still…). We started our meal with a classic Peruvian/Chilean cocktail, the Pisco Sour.

Pisco (pronounced peas-co, not piss-co; if it sounds like something your really wouldn’t want to drink, you’re pronouncing it wrong ?) is a spirit distilled from grapes. Chile and Peru have been feuding for years about which country first distilled it, but it appears that most agree that it was Peru. However, it is still a topic than can can cause heated arguments between Chileans and Peruvians. It’s best to treat this like politics and religion when in these countries—just try not to discuss it. For the record, I have had delicious, and awful, Piscos from both countries. There are several different kinds of Pisco distilled from several kinds of grapes and aged in different ways for different lengths of time. I won’t go through all of that here, as you will be lucky to find even one or two Piscos in your favorite liquor store, although not so long ago you would not have found any. Grab a seat at one of the better cocktail bars in town, especially at someplace like Rural Society or Tanta that focuses on South American cuisine, and the bartender may have several for you to sample.

Regardless, both countries produce excellent examples and both claim the Pisco Sour as a national drink. There seems to be no dispute that the cocktail was invented by an American (!?) living in Lima in the 1920s. His name was Victor Vaughen Morris. He opened a saloon in Lima in 1915 and was known for getting creative with cocktails. How popular is the drink? In Peru they declared a national holiday in honor of the Pisco Sour.

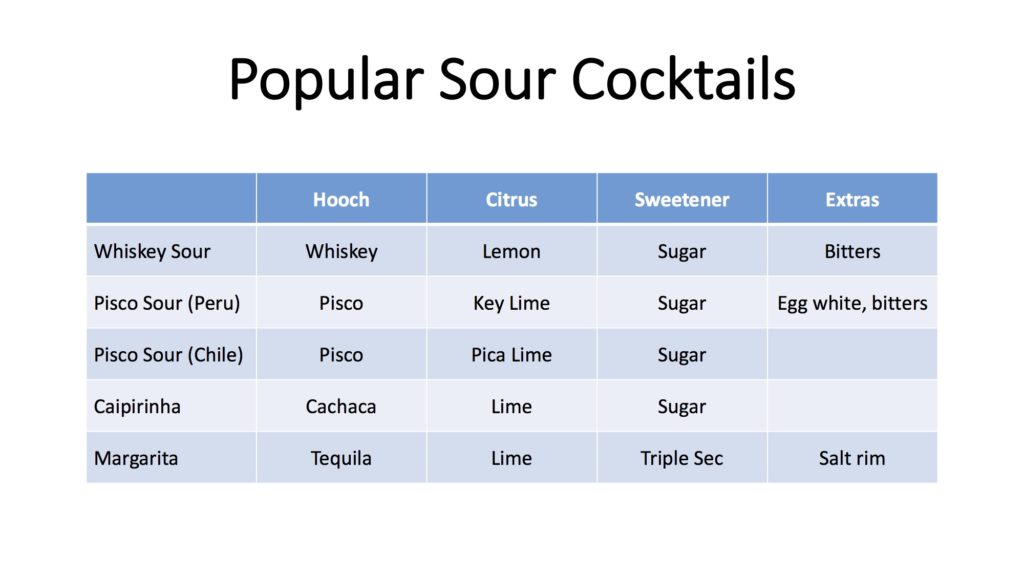

You have probably heard of a whiskey sour (whiskey, lemon juice, sugar), but you may not have realized that a Margarita (Mexico) is a “Tequila Sour,” a Mojito (Cuba) is a “Rum Sour,” and a Caipirinha (Brazil) is a “Cachaça Sour.” There is an entire family of “sour” cocktails made of your liquor of choice, some citrus juice (lemon, lime or a combination), a sweetener to balance the sour citrus and perhaps an additional ingredient or two.

While a “classic” version of each of these cocktails would use the ingredients listed, bartenders—and you—are free to substitute and vary proportions as the spirit (pun intended) moves you. There are dozens, maybe hundreds, of variations on this theme using different liquors, citrus juices, sweeteners and extras. I do hope you will use fresh citrus juice, however. It’s a little more work to squeeze it yourself but the improvement in flavor is enormous.

Why is this kind of cocktail popular? They are very refreshing in warm weather and make inexpensive booze into delicious drinks. While many bars and restaurants will charge premium prices to put premium hooch in your sour, the citrus is going to mask all of the nuances that make premium booze, well, premium. Drink the expensive stuff neat or in another cocktail that let’s the flavors and aromas shine.

Here is a shot video on how to make a Pisco Sour. This is a classic Peruvian version using a little less sugar (simple syrup) than some recipes call for, which I prefer. You, of course, will adjust the ingredients to your taste.

Mr. Ehrmann mentions that he usually uses a “dry shake” with this cocktail. Egg whites are harder to emulsify when the other ingredients when cold, so, when they are used in a cocktail, all of the liquid ingredients, including the egg whites, are placed in the shaker with no ice and shaken for a minute or so to get a good emulsion, then ice is added and the drink is shaken again to chill it. You can do it all at once as in the video by shaking really hard, or you can do as I often see in South America: use a blender, especially of you are making multiple Pisco Sours at once.

A word about the use of raw egg whites in a cocktail. I am not a medical doctor, a nutritionist or an epidemiologist, so I offer no recommendations. Check with your doctor if you are concerned, or use pasteurized eggs. By the way, the Whiskey Sour was originally made with an egg white as well. I believe it improves that drink considerably.

While we were enjoying our Pisco Sours, some of the first plates arrived at the table.

The bread basket was terrific. You probably know that Focaccia is an Italian bread baked fairly flat and topped with all sorts of good things that can include, olive oil, herbs, olives, garlic, cheese and/or onions. These are the traditional toppings, but creative bakers sometimes wander far afield from these, sometimes successfully, sometime not. This one was topped with onions and garlic, but this may vary on your visit.

Why an Italian bread in an Argentinean restaurant? There have been several waves of immigrants from Italy to Argentina. The Spanish may have conquered and claimed it, and Spanish is, of course, the official language, but you will find a strong Italian influence in the language, the food and the culture. It’s a beautiful thing, as are the people resulting from the mingling of the two countries.

The second bread in our basket, Chipas, is gluten-free. It was apparently created in Paraguay a couple hundred years ago and has been popular there and in Northern Argentina since long before “gluten-free” was a thing. Originally made with just tapioca flour and water, more modern recipes include eggs and dairy (cheese). These were added after the Spaniards brought chickens and cows to the region. There is a popular variation in Brazil as well, where it is called Pão de Queijo (Cheese Bread). Here is a delightful video made by a young girl named Stephanie showing you how to make Chipa.

You’ll notice in the comments on this video (and on other videos and articles on Chipa) that Paraguayans can be quite vocal in defending Chipa as only from Paraguay. Certainly the original recipe was developed there, but it has been modified and integrated into other countries as well, most notably Argentina and Brazil. It’s a bit like the Pisco wars between Peru and Chile. Best just to enjoy the bread and stay out of any discussions of what is “real” chipa.

Chipa is similar to French Gougères, which are made with wheat flour and (traditionally) Gruyère cheese, and are also totally delicious, like Chipas. The ones at Rural Society made with Sardo and Cheddar cheeses, came out warm and melt-in-your-mouth tender. Sardo was originally a hard, cow’s milk cheese from Sardinia, where Perorino Sardo is also made from sheep’s milk. The Argentineans (no doubt some of those Italian immigrants) make their own cow’s milk version. I honestly don’t know if Rural Society used the Italian or Argentinean version and didn’t think to ask, but either would be entirely appropriate.

While bread purists might eat it solo, most of us like a little something to smear on our bread or to dip our bread into. Rural Society provides some options.

The two sauces and the butter can be used in different ways all through the meal. Each is great on bread, but each can also enhance the meat and vegetable courses that came later. All up to you, of course.

The Malbec butter was simply butter mixed with Argentinean Malbec wine (more on that later).

In the middle of the trio of condiments above is a Salsa Criolla (Creole sauce). You have probably seen and enjoyed many types of salsa in your favorite Mexican restaurant or in the deli of most supermarkets. They are made with many different combinations of tomatoes, tomatillos, onions, chiles, green or red bell peppers, garlic, cilantro and petty much anything the cook decides to throw in. They ingredients can be chopped pretty coarsely or puréed smooth. In Peru, Salsa Criolla is an onion-based condiment that, like the salsa in your favorite Tex-Mex place, can be served with just about anything. There are as many variations as there are mamcitas in Peru, but it is typically made with thinly sliced red onions, lime juice, white vinegar, parsley and/or cilantro and a little olive or vegetable oil. Peruvians tend to like things spicier than Argentineans, so Salsa Criolla Peruano often includes some aji amarillo (yellow chili pepper) paste. Aji amarillo, as the name implies, is a yellow chili pepper that is common in Peru. It is harder to find fresh in the US, but is more easily found dried or as a paste in a jar, as it is often used in Peru as well. It is a medium to hot chili, so you adjust the amount for your own taste and tolerance for heat. A typical, basic recipe for Salsa Criolla Peruano is at LimaEasy. If your local supermarket does not carry fresh, dried or jarred aji amarillo, good old Amazon will come through for you.

Salsa Criolla in Argentina, however, is, typically, more similar to the tomato salsas from Mexico that are ubiquitous in the US, although other ingredients are as important as the tomatoes. Again, there are as many variations as there are cooks making it, but it is usually made with tomatoes, onion, red and green bell peppers, garlic, vinegar, parsley and olive oil. A typical recipe is found here, but you can vary all the amounts, add other vegetables and, if you like it spicy, add some red pepper flakes or a finely diced chili in amounts to give you the heat level you prefer.

The condiment most commonly identified with Argentina, however, is chimichurri. This is a green sauce made with lots of herbs, some garlic, lemon juice, vinegar, olive oil and (optionally) some red pepper flakes. It goes great with grilled beef, chicken, fish, lamb or vegetables. It’s as easy as tossing big handfuls of cilantro and parsley, some oregano, peeled garlic cloves, vinegar, lemon juice and olive oil in a blender or food processor and letting it rip. Here is a detailed video that also has a recipe printed in the comments below it.

The next dish to appear might bring a “Ewwww!” from some of you, but bear with me as I explain.

Lengua a la Vinagreta is pickled, smoked veal tongue sliced thin and served with a demi-glace sauce, grape mustard and pomegranate seeds. For many Americans, the thought of eating a cow’s tongue, especially a baby cow’s tongue, may not sound too appetizing, but, when properly prepared, it is tender and delicious. Veal or cow tongue is not terribly difficult to prepare, but it does take a while. Simmer the tongue for two or three hours in water or broth with (or without) aromatic vegetables and herbs (longer for beef tongue). When the meat is tender, cool for 10 or 15 minutes, then peel off the rubbery skin. Or you can skip all that and find it in your local deli.

In any event, no matter how odd you think eating tongue may be, any non-vegetarian is likely to love this dish. The meat is meltingly tender, the sauce is rich and the mustard and pomegranate add some bright notes.

By this time our Pisco Sours were gone, but (unsurprisingly to anyone who knows me) I had ordered a bottle of wine to go with dinner. Wine parings are available with the tasting menu, but, after consulting with my fellow diners, I opted to go on my own this time. After perusing the wine list, I had a strategy for a couple of nice bottles for my red wine-loving companions, and the first part of the strategy was the 2010 Catena Zapata, Nicasta Vineyard, Malbec, La Consulta, Mendoza, Argentina.

That’s a pretty long name for a wine, so let’s break it down. First, the grape: Malbec. Malbec is a dark red grape that is relatively difficult to grow. It is susceptible to disease, frost and other problems, although newer clones and vineyard management techniques have reduced these problems. It is used as a blending grape in Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot-based wines in France, California and elsewhere. It is added in small amounts (up to a few percent) to deepen the color and add tannins that help the wine age. In Cahors, France, the red wines must be at least 70% Malbec, but these are big, rustic, tannic wines.

There is, however, something magical about the soil and climate in parts of Argentina that produce Malbec with a very different character. The Malbec berries in Argentina are smaller and have more complex flavors than their counterparts in most of the world. It is thought that the cuttings brought over in the 19th century may have been from a clone that is no longer found in France, but that is not certain. It is certain that in the last years of the 20th century and the beginning the 21st century, winemakers in Argentina started to elevate the quality of Malbec considerably.

Dr. Nicolás Catena Zapata grew up in Argentina in a family that had immigrated from Italy in the late 1800s (I told you Italians were important here!). His grandfather planted Malbec in in 1902, and his father continued the tradition. Both were convinced Malbec could produce great wine in Argentina, but they never quite figured out how. Besides, Argentina was mostly known for jug wines in the 20th century and was not even a reliable source of those when some of the military and political upheavals made production and export of anything difficult.

Nicolás did not share his father’s confidence in Malbec, but, after his father died in the 1960s, he took over the family business and strengthened the production and distribution of all of the family’s wines within Argentina. In the 1980s, he spent several years as a Professor of Economics at the University of California at Berkeley, which gave him the opportunity to spend a lot of time in the wine country of Northern California. He was inspired by the dynamic evolution of wines there, and went back to Argentina determined to try to realize his father and grandfather’s vision. He experimented with a variety of clones and vineyards to find the right grapes and climate for Malbec. He found that the clones already in Argentina planted at higher elevations in Mendoza would produce an excellent wine. He bottled his first Malbec in 1994. His experimentation continued, and by the turn of the century his wines were being sought by wine lovers in many countries. Today, Bodega Catena Zapata is recognized as a leading producer of world-class red table wines made from the Malbec grape. Their name on the label is a close to a guarantee of quality as any. (those are my words, even though they sound like I took them from a Zapata sales brochure. ?)

Mendoza is the most important wine-producing province in Argentina; about 2/3 of the annual production is grown there. It is also the region where Catena Zapata is based and where Nicolás found the secrets to making great Malbecs. Here is a map, courtesy of the Catena Institute of Wine, which the family founded to enhance the quality of winemaking across Argentina.

The Nicasia Vineyard (very near the center of the map), in the La Consulta region of Mendoza is one of the high-elevation sites that Nicolás found would produce excellent Malbec.

Whew! I think that covers everything in the name: producer, vineyard, grape and region. After all that, was the wine any good?

Oh, yes. Dark purple-red, with a rich nose of black fruits, spice and oak. All of this carried through on the palate, backed up by good acidity which provided freshness and still some light tannins. It is drinking beautifully right now.

With that wine we need more food, and it came soon enough. Next, a Burrata salad…

…was joined by Empanadas de Espinaca.

Burrata is a very special form of Mozzarella cheese. The Mozzarella is made as usual, but instead of being rolled into a ball, the still warm cheese is stretched flat and formed into a pouch that is filled with Mozzarella scraps and a shot of fresh cream. When cut into, the cream and cheese on the inside ooze out in a rich, buttery mess. The richness of the cheese was balanced by the acidity of the reduced balsamic and charred (love how they toss anything they can on the parrilla or wood-burning grill) and the bite of the arugula.

Empanadas are found all over Latin America, and variations on the theme are found in almost every country in the world. They are small (2 or 3 bite-sized) pastries that can be filled with almost anything: meat, vegetables, cheese or combinations thereof.

Empanadas de Espinaca are spinach (espinaca) stuffed empanadas. In addition to the spinach, there is usually some garlic, maybe some cheese or cream, often some eggs, or whatever the cook decides to add. I have often been served one spinach empanada and one meat filled empanadas as an appetizer in a South American restaurant. They can be thought of as upscale Hot Pockets, I suppose, but they are delicious. Rural Society’s version included Swiss Chard (upscale spinach), roasted onions and more Sardo cheese.

Moving on, we came to the serious meats that Argentinean steakhouses are appropriately famous for.

Yep, it’s a grilled sausage, but what a sausage. Made with beef and pork, richly seasoned (but not spicy) and charred perfectly over the hot, smoky grill leaving it juicy and full of flavor.

Perhaps you know Mexican chorizo, which is usually made of pork (although many other meats can be used), heavily seasoned with garlic and spices, sometimes quite spicy, and sold raw. It must be cooked before it is eaten. It is often taken out of its casing and cooked as a loose crumble.

Spanish chorizo is a dried, salami-like product, made with pork and pork fat that has been coarsely chopped. The characteristic seasoning is smoked Spanish paprika, either sweet or spicy.

Argentinean chorizo is unlike either. It is made wth a combination of pork and beef, is not spicy, but is well-seasoned. It is sold raw and must be cooked. It is a bit like Italian sausage (does that surprise you?) in texture, but the spice mixture is quite different with none of the fennel seed that characterizes Italian sausage.

By now the first bottle wine was empty, though we were still enjoying it in our glasses. I asked the waitress to go ahead and decant and pour the second wine I had selected, the 2013 “Caro.”

Like the first wine, it is from Mendoza, but is made by a joint-venture between the Rothschild family of Bordeaux’s Chateau Lafite and Nicolàs Catena. It is a 50-50 bend of Cabernet and Malbec, and is an even deeper, darker wine than the first bottle we opened. Lots of black plums, blackberries and black currants on the nose with some nice violet and other floral notes seasoned with a bit of something like Chinese 5-spice aromas. Really big in the mouth, the fruit is dominant with all he other notes blending in. It has the balanced acidity needed to marry well with food and noticeable, but soft, tannins. Obviously younger than the 2010 Malbec and, with the Cabernet in the blend, perhaps built for a longer life, though it is drinking very well now.

Bigger wine = bigger meat. Lamb chops, anyone?

Unless Argentina has taken over Colorado and I missed the news reports, we have obviously left not only Argentina but South America to source the lamb chops. That’s OK. Colorado lamb chops are as good as any in the world, especially when seared medium rare over a hot wood fire. Tender and juicy and washed down with good red wine, what’s not to like?

More meat, you say? OK. How about a nice ribeye of Uruguayan beef? (As you may remember, I mentioned earlier that Argentinean beef cannot be imported into the US, but Uruguayan beef can.) For some reason I failed to take a picture of the steak but it looked like, well, a grilled ribeye. Like the lamb, perfectly seared over a hot grill and seasoned with nothing more than salt and pepper and wood smoke. Yum

But, as your mom would say, you have to eat your veggies. How about some grilled asparagus with bagna càuda?

I stopped boiling or steaming asparagus years ago. Grilling concentrates the flavor, gives some tasty charred bits and, depending on the type of fuel you are using in your grill, some smoky flavor. It takes only a few minutes. Rub them with a little olive (or other) oil, salt and pepper and toss them on the grill, turning them to get the amount of char you want on all sides. Other flavorings, like garlic powder, are optional (fresh garlic tends to burn). If it’s too cold for the grill, toss them in the oven or under the broiler spread in a single layer and, if you like, topped with grated Parmesan.

Bagna càuda is a traditional from Piedmont, Italy. The name is derived from Piedmontese (not Italian) words and means “hot dip” or “hot sauce.” You will often see it translated “hot bath,” but that is not correct. If the words were Italian, they would be a grammatically incorrect version of “hot bath,” but the name is from the Piedmont dialect. (Sorry, getting way too deep in the weeds on that one.) It is made with olive oil, anchovies, garlic, butter and sometimes cream. As with all of these simple, country dishes, there are a million variations, although I have no doubt that the one your Nona made was the most authentic and best ever. ?

This is another example of the strength of the Italian influence in Argentina as it is integrated into the cuisine across the country, especially in central Argentina. The dip is traditionally served with raw or cooked vegetables and some bread, but, like a good salsa or chimichurri, it goes well on most anything. If you don’t like anchovies, give it a try anyway as the flavor blends in with the other components of the dish. I suppose you could leave the anchovies out, but then you really just have garlic oil and butter; not a bad thing, but not bagna càuda.

I like this video that shows how to make a use one quite traditional version of bagna càuda, even though the chef translates it as “hot bath.”

If you have meat and veggies, you have have some potatoes to go with them.

Potatoes, as you may know, are native to Peru where you can still find several thousand varieties being grown. The ancient Incas mastered ways to grow them and preserve them. You’ll find potatoes used in many ways all over South America and, of course, the rest of the world. This particular recipe is one I had not had before, but it was delicious. I’ve had cheesy potatoes, garlic potatoes and even cheesy garlic potatoes before, but the Mozzarella curd was a first. As you might expect, the cheese gave the potatoes a rich, velvety finish.

We were pretty full by now, but we couldn’t leave without a postre (dessert).

Rogel, or Rogel Torta (torta means “cake”) is a popular dish in teahouses and upscale restaurants in Argentina, where it is also a traditional wedding cake. In it’s most basic form, it is simply layers of pastry that have been baked and stacked in layers with dulce de leche spread in between, topped with an Italian (again with the Italians!) meringue. The result is a dessert that combines the slight crunch of baked pastry with the caramel-vanilla richness of dulce de leche and the sticky-sweetness of the meringue. You will, of course, find a thousand variations on the recipe and endless arguments on what constitutes an “authentic” Rogel Torta, but you can play with these ingredients a lot of ways and still make something delicious..

I should note that the pastry in a Rogel Torta is traditionally an egg enriched, usually sweet, pastry rather than a simple pie crust pastry, but I have seen recipes that vary widely. Once again, I’m sure your Nona’s was the best!

The pastry chef at Rural Society upped the ante a bit by using puff pastry instead of regular pastry and adding a smear of lemon curd, which gave a nice, tart, counterpoint to the other ingredients. I’m not sure what purists would think of the changes and, frankly, I don’t really care as this was delicious.

You can buy good quality dulce de leche in most supermarkets these days. La Tienda carries an excellent one.

You can make your own dulce de leche from scratch. It’s not difficult, although it does require close attention, and it takes a long time. If you are a dedicated baker/pastry chef you may well find this worth the effort.

There is a much easier method that I have used and Valeria uses as well (she loves dulce de leche all by itself, nothing else needed!). Simply submerge a can of sweetened condensed milk in water and boil gently. About three hours later, let the can cool and open it up to spoon out the goodness. Here is a short video that explains the basic method, some important safety notes and some alternative methods.

Pastry sheets are harder to get by mail order since they need to be frozen. They are generally sold in bulk packs with fairly high shipping costs to ensure they arrive frozen. I have never seen a sweet pastry in the freezer section, so please let me know if you know a source. You can, of course, make your own pastry or puff pastry. The sweet, egg-enriched pastry that is classic for Rogel can be made fairly simply. Here is the technique.

Italian meringue is a little trickier to make than French meringue, which is the one most commonly made in home kitchens. If you have made meringue at all, it was probably just egg whites whipped to soft or stiff peaks, then some sugar is whipped in, and maybe a little vanilla for flavor. That’s French meringue. Italian meringue is made by first cooking a hot sugar syrup to the soft ball stage. The egg whites are whipped to stiff peaks, then the hot sugar syrup is whipped in. Italian meringue is more stable than French meringue. Here is a video with the details of how to make it.

I found some videos showing the whole process of making Rogel, but they all seem to be in Spanish. Really, though, the Torta does not require a recipe. Make or buy your favorite pastry and bake several sheets into whatever size and shape you like. Make or buy some dulce de leche and spread it between the pastry layers as you stack them. Top with some Italian meringue and, if you want to get fancy, brown the meringue a bit with a kitchen blow torch or briefly under a hot broiler. If you want to use French meringue instead, I won’t judge (though Argentinean foodies might ?). Heck, I don’t care if you top it with whipped cream. It’s your cake! It may not be an authentic Argentinean Rogel Torta, but it will still be delicious.

So, there you have a culinary tour of South America as seen through the tasting menu at Rural Society. It is certainly not comprehensive. We didn’t touch a single seafood dish and the seafood in the countries on both the east and west coast is amazing. The range of cuisine in a culinary capital like Lima, Peru is enormous, and the menu her does not (and could not) begin to cover that. We sampled a couple of excellent Argentinean wines, but there are plenty more that are worth learning about and an even wider selection from Chile. Still, if you are a meat eater and would like to get some feel for (or taste of) a small slice of South American cuisine, the food here is excellent.

One last caveat that may matter to some. The key cooking device here is a large, wood burning parrilla (grill). You will smell the aroma of burning wood, which is like perfume to me, since I love wood-grilled food, but which some people may not enjoy. Just FYI.

Rural Society

Address: 455 North Park Drive Chicago, IL 60611

Phone: (312) 840-6605

Reservations: opentable.com

Website: http://www.chicago.ruralsocietyrestaurant.com/

Dress Code: Business Casual

Price Range: $30-50

Hours: Breakfast: Saturday & Sunday: 7:00am – 11:30am

Dinner: Sunday – Thursday: 5:30pm – 9:00pm, Friday & Saturday: 5:30pm – 10:00pm

Credit Cards: AMEX, Discover, MasterCard, Visa

Chicago, IL 60611

The author has no affiliation with any of the businesses or products described in this article.

All images were taken with a Sony Alpha a6300 camera and a Sony-Zeiss SEL1670Z Vario-Tessar T E 16-70mm (24-105mm full frame equivalent) F/4 ZA OSS lens or Sony 35mm (52mm full frame equivalent) F/1.8 E-Mount Lens using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.

사설바둑이

21 Aug 2021Hi there! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering

which blog platform are you using for this website? I’m getting sick and

tired of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform.

I would be fantastic if you could point me in the

direction of a good platform.

my site :: 사설바둑이

DavePruett

23 Aug 2021This is a WordPress site.