I love Champagne. Real Champagne. Capital “C” Champagne from the region of the same name in France. To my taste, almost all of the great wines that France has given the world have been equaled (not duplicated, but equaled) elsewhere in the world. Except Champagne. There are some wonderful sparkling wines being made in California. A good German Sekt or Spanish Cava can be a delightful aperitif or a base for a Kir Royale or other Champagne cocktail. I know many people who love a good Prosecco from Italy. To me, however, there is still nothing quite like Champagne. Your taste may vary and I respect that, but Champagne for me, please.

If you read my earlier post on Sepia, then you know that I have a very high opinion of the chef, Andrew Zimmerman, and the food, wine and cocktail program there. On this I do have expert opinion on my side, as the folks at Michelin have granted them a star every year since they began rating Chicago restaurants in 2011. So, you can imagine how happy I was to receive an announcement of a dinner at Sepia featuring the wines of Taittinger, one of the premier Champagne producers. It did not take long for me to sign up, which also made Valeria very happy because she loves Champagne and Sepia, too (Happy Wife, Happy Life).

The history of Champagne Taittinger is long and interesting. The company’s story begins in 1734 when Jacques Fourneaux decided to start a wine business based in Reims, Champagne. Once again I am grateful to the folks at Wine Folly for their excellent wine region maps. You can see Reims at the northern end of the Champagne region.

You may know that Dom Pérignon, the luxury Champagne produced by Moët & Chandon, is named after a Benedictine monk (1638–1715) and cellar master who, according to legend, discovered (or invented) the Champagne method for producing sparkling wines. The good Monk did not do that, but he was an outstanding winemaker known for his efforts to improve the quality of the wine he produced and innovations such as the use of cork to seal and preserve bottles of wine.

When Jacques Fourneaux, who had made his fortune in textiles, began his wine business he worked closely with local Benedictine monks, who had acquired Dom Perignon’s techniques, to learn how to produce quality wines. Monsieur Fourneaux produced still and sparkling wines and his business did OK until 1820 when Jérôme Fourneaux, Jacques great-grandson, formed a partnership with Antoine Forest. Forest-Forneaux grew quickly, expanding exports rapidly, especially to growing markets in Britain and the United States. Forest-Forneaux did well for 100 years, until the 1920s when the combination of the First World War, Prohibition, and the Great Depression almost destroyed the business.

As luck would have it, however, a young officer named Pierre Taittinger was sent to the Château de la Marquetterie when he was wounded during WWI. The château had been built in the 18th century and planted in Pinot Noir and Chardonnay (two of the three grapes used to make Champagne) by (again) Benedictine Monks. Taittinger fell in love with the château and the surrounding countryside and vowed that he would purchase it if the opportunity arose.

In 1930, Pierre bought the struggling Forest-Forneaux business, which became Champagne Taittinger. Two years later he bought the Château de la Marquetterie, just as he had promised himself he would. At about the same time, he bought the Comtes de Champagne (Counts of Champagne) mansion in Reims. This property has been build in the 13th century and, as the name implies, was the home of royalty and aristocrats in Champagne over the centuries that followed. (It is now the headquarters of Champagne Taittinger). Pierre predicted, correctly as it turned out, that tastes would turn away from the traditional rich, heavy sauces and very sweet Champagne (more on that below) that had been popular in the past. He began a trend toward lighter, drier Champagnes. His son, François Taittinger, cemented these ideas into the culture of the company. They controlled more and more vineyards and upgraded their winemaking techniques with an emphasis on quality over quantity.

As sometimes happens, however, the family overreached. In the 1990s, the family branched out into other luxury goods and hotels. Unfortunately, that created more financial strain than the company could manage. They were forced to sell the company to the Starwood Hotel Group in 2005. Some family members were not happy with the sale, however, and in 2006, Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger, Pierre Taittinger’s grandson, was able to work a deal to repurchase Champagne Taittinger.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a video must be worth a million so, rather than write a long explanation of how Champagne is made I’ll let a video from The Science Channel do the talking.

The Bollinger Champagne featured in the video is another favorite of mine. It’s made in a very different style than Taittinger, but we’ll save that for another day.

One more point before we move on to dinner: what is the correct way to pronounce Taittinger? You will hear TAT-in-ger. TAIT-in-ger, Ta-tan-jay and other variations. I doubt the owners or anyone selling you the wine cares all that much how you pronounce it as long as you ask for it. If, however, you would like to be true to the French pronunciation, it goes like this:

I flop back and forth between the two and have to admit that, over the years, I have probably slaughtered the pronunciation in a variety of ways. Personally, I will not quibble with how someone who is pouring me an excellent Champagne pronounces the name, but it is nice to get these things right.

As we arrived at the restaurant for the special dinner, we were greeted by Arthur Hon, the very knowledgable and talented Beverage Director at Sepia, with the tub of non-vintage Taittinger La Française Brut pictured at the top of this article. If you have ever had a Taittinger Champagne, it was most likely this one. It is widely available, generally very highly regarded, and is reasonably priced for wines in this category. Prices for non-vintage champagnes can vary widely depending on the strenth of the dollar, the time of year and where you live, but you may find La Française in the $35-50 range, perhaps less on sale, especially around the holidays.

Almost all Champagne producers, especially the large ones, offer several different bottlings of Champagne. The one produced in the greatest volume is almost always a non-vintage (NV) brut. Non-vintage means that the wine is a blend of wines made from grapes grown in different years. Brut means the wine is very dry, that is, has only a very small amount of sugar and little, if any, discernible sweetness. A Brut Champagne can have as much as 1.2% residual sugar, which may sound like a lot, but remember that grapes picked to make Champagne are generally less ripe and therefore have less sugar and more acid in them. You may recall, if you watched the video on making Champagne, that the still wine that is turned into Champagne is fermented dry and has only about 10% alcohol, versus 12.5%, which was the traditional average for a “normal” table wine and up to 15 or 16% for some of the huge wines made today. In winemaking, more sugar in the grapes = higher alcohol when fermented into wine (assuming all the sugar is allowed to ferment).

Think about making lemonade. You have to add a lot of sugar to the lemon juice to balance out all the acidity in lemons and even more to make the lemonade sweet. Champagne grapes are nowhere near as acidic as lemons, but the same principle holds—a little sugar balances the acidity without producing a sweet wine.

While Brut Champagnes are by far the most common, several other types can be found.

- Extra Brut (less 0.6 % residual sugar)

- Brut (less than 1.2%)

- Extra Dry (between 1.2 and 1.7%)

- Sec (between 1.7 and 3.2%)

- Demi-sec (between 3.2 and 5.0%)

- Doux (5.0% or more)

Historically, Champagne was sold as a sweet wine consumed mostly after dinner. Champagne made for the British market was the driest and more often consumed with dinner, but it was still made with 2.2 to 6.6% residual sugar. The Russians really loved their Champagne sweet, so wines for that market clocked in at 20 to 30% residual sugar.

It is trendy today to make Champagnes that are drier still (<0.3% residual sugar) and you will see them labeled “Brut Nature,” “Brut Zero,” or “Brut Non-dosé.” If you want to make these very dry Champagnes, however, you can’t just leave out the dosage (that small amount of sweet water or grape juice added at the end of the production process as detailed in the video). You have to start in the vineyards and grow and pick grapes that will not have so great an acidic edge in the end. Unfortunately, not every producer has mastered this. Most of the good ultra-dry Champagnes come from small grower-producers, not the big Champagne houses.

The major Champagne houses make their NV Brut in a consistent style. While the Champagne producers may not like the comparison, NV Brut Champagnes are like Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Sprite; each producer has a house style with a distinctive taste that is the same year after year no matter if you buy them in New York or New Zealand. The Taittinger La Française is a lighter, more elegant style while the Bollinger, for example is a heavier, bigger style. One style is not inherently better than another, but you might choose a different style depending on you mood, the time of day or what food (if any) you are having with the wine. But, as we shall see as we continue through the meal, a typical Champagne producer will produce other wines that can very significantly with the vintage.

If you are a wine lover, this is a wonderful sight to see.

After we sipped on the Le Française and waited for all the guests to arrive, we were seated and Mr. Hon introduced himself and the guests representing Taittinger.

Time to do some serious tasting of both food and Champagne. There is an old saying in the wine industry: “Buy on bread, sell on cheese.” The idea is that bread cleans your palate and lets you smell and taste any subtle defects in a wine while cheese dulls the palate a bit and will help mask small problems. I’ve never really tested this to see how much difference it really makes, but it is always nice to have some good bread on hand when tasting wine.

Sepia served a multi-grain roll that was pretty darn tasty all on it’s own, but something far more delicious came along immediately thereafter.

The famous Foie Gras Royale has been on the Sepia menu forever. I suspect it is one of those dishes that, if the chef removed it, riots would ensue. The gelée that covers the foie gras mousse varies with the fruit that is in season or perhaps the whim of the chef that day. No matter. The rich, delicious mousse spread on the rich, buttery, perfectly toasted brioche and complimented by a touch of sweetness from the gelée and the crunch of the Marcona almonds is just perfect.

It is also the perfect foil for a nice glass of Champagne.

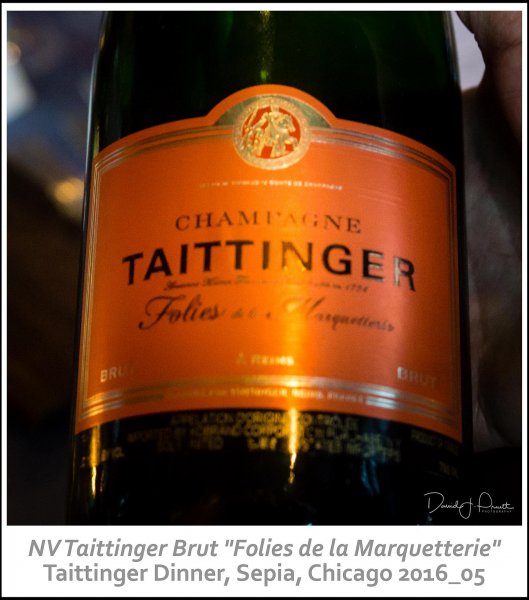

Folies de la Marquetterie is a single-vineyard wine that is produced from grapes grown around the Château de Marquetterie that Pierre Taittinger fell in love with and eventually purchased in the early 20th century. It is very limited in availability and you will rarely, if ever, see it on a retail shelf. I had never tasted it before this event. It is 45% Chardonnay, 55% Pinot Noir and aged 5 years before release. It is said to be produced from single vintages, though no vintage is declared on the labels. The aromas and flavors show the characteristic Taittinger lightness and elegance due to the high proportion of Chardonnay, but the long aging on the lees (the solids that fall out of the wine as it ferments in the bottle) adds a great deal of toasty, yeastiness to the bright citrus and peach fruit flavors and aromas. While elegant, it still had the body to stand up to the rich foie gras dish.

Next on the menu, a nod to Japanese—or would that be Italian?—cuisine.

Crudo is Italian for “raw.” The Italians enjoyed their own form of what most of us think of as sashimi, pesce crudo (raw fish), long before Japanese sushi, sashimi and related dishes became all the rage. At it’s simplest (and Italian food is all about simplicity) pesce crudo is just thinly sliced, impeccably fresh raw fish drizzled with some good olive oil and an acid of some kind—lemon or another citrus is most common. A sprinkling of some fresh herbs or other flavor enhancements is not unusual.

Kombu is a type of seaweed (kelp) used in Japanese cuisine. In this case, olive oil was infused with kombu and drizzled on the fresh salmon. Ponzu is a Japanese citrus sauce that is often combined with soy sauce. Infusing Ponzu with blackberries makes this, like the kombu infused oil, a true fusion ingredient.

Both the green and purple-red leaves you see on top of the fish are varieties of shiso, a Japanese herb. One of it’s alternative names is Japanese basil and it does, in fact, taste somewhat like basil, but it is more complex than that; it also tastes of mint and cinnamon and licorice.

Ōra King Salmon is a farm raised salmon from New Zealand. When I see salmon labeled “farm raised” in a grocery store or on a menu I proceed with caution. Some salmon farms have pens that are packed with fish swimming in their own waste, artificial growth hormones and whatever else the farmer uses to raise the fish quickly and cheaply. This you do not want, or at least I don’t.

There are, however, salmon farms that are environmentally responsible and humane and which raise their fish as naturally as possible. (I realize that vegetarians consider any sort of animal husbandry and consumption inhumane. While I respect those views, I do not share them.) Ōra King Salmon is about as high on the quality scale as you can go, as you would expect in a Michelin-starred restaurant. They have their own breeding program to select the very best King Salmon and they control every step of their sustainable farming practice. I’ll refer you to their website if you would like more detail, but I can tell you this salmon just melts in your mouth. (I have also enjoyed it on the sashimi platter at Roka Akor.)

But, hey! Aren’t we here for Taittinger Champagne? Yep.

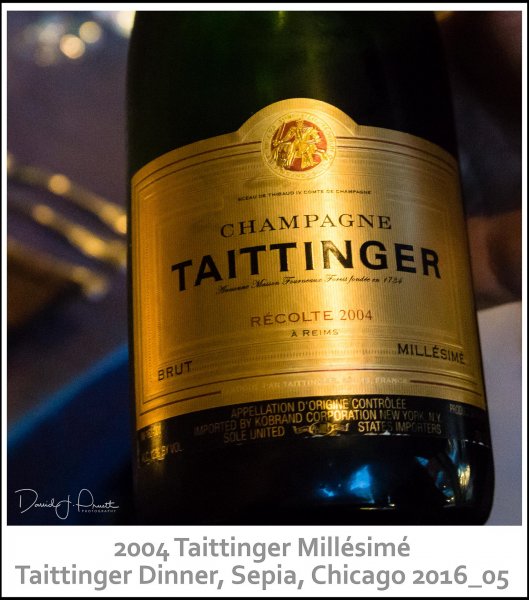

As with Vintage Port, Vintage Champagne is generally only produced in years the winemakers feel are exceptional. They will reflect the house style, but will show more variation, reflecting an individual vintage, than the NV blends. The Taittinger Millésimé (Millésimé means “vintage”) is typically a blend of 50% Chardonnay and 50% Pinot Noir all from Grand Cru vineyards. It is aged five years on the lees (yeast cells and other solids that settle out of the wine after fermentation) before it is disgorged and sold. The 2004 shows the typical light, fruit and citrus nose of a Taittinger Champagne, but there was also a fair amount of toasty yeastiness from the time spent on the lees. This is a classic Brut Vintage Champagne that retails in the neighborhood of $80, but, as always, the price will vary significantly based on where and when you shop.

The crudo and the Millésimé were great together, so how about anther fish course?

Stone Bass is a deep water ocean fish also called Wreckfish. The names come from the fact that it is often found around shipwrecks or near rock ledges. It is a large fish, similar to Grouper. The flesh is white and mild flavored.

Shanton broth is a rich, complex meat stock used in Chinese soups and other recipes. The name appears to be an abbreviation (or corruption) of shang tang, which means “superior stock.” It is made using a combination of pork, chicken and beef with a little dried longan (a southeast asian fruit similar to lychee) and white peppercorns. You can find Iron Chef Morimoto’s recipe here. Add some white asparagus and a dab of caviar and you have a dish with a lot of flavor and texture.

Two Champagnes were poured with this dish. The first was the NV “Prélude” Grands Crus Brut.

The NV Prélude, like the vintage Millésimé, is a 50/50 blend of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir from Grand Cru vineyards and it is also aged five years on the lees. The difference is that the Prélude is blended using base wines from several years in order to maintain a consistent style, rather than one that reflects a single vintage. Along with the characteristic citrus and peach aromas, I thought there was a hint of red cherry or strawberry here.

The flagship of the Taittinger line is their Comtes de Champagne Blanc de Blancs, their luxury Cuvée that stands with Dom Perignon and Cristal among Champagnes that are generally considered the finest in each vintage they are produced.

The name should look familiar as it is named after the 13th century mansion that now serves as Taittinger’s headquarters as we discussed earlier. Blanc de Blancs means “white from whites,” which is used to describe a white wine made from 100% white grapes. In this case, 100% Chardonnay. The 2006 was an outstanding example of this wine. It somehow manages to be both elegant and powerful at the same time, with lots of ripe fruit aromas and flavors, some floral notes and great body.

OK. Enough wth the seafood. How about some more substantial meat?

I love duck. Give me a good confit (slow cooked in duck fat) leg and thigh section or a pan-fried breast with maybe a little Port and garlic sauce and I’m happy. While the breast is “supposed” to be cooked medium-rare, I prefer mine medium, if you don’t mind. This one was classic medium-rare as it was being prepared for the whole table rather than ordered individually. I was OK with that; I play nice with others. The poached radishes were a delicious complement to the duck. Radishes are terrific raw and cooked and they are pretty cheap, but they seem underutilized. Guanciale is (approximately) pancetta made with pork cheek instead of pork belly. I say “approximately” because, depending on a particular butcher’s seasoning and curing techniques, the two can be very similar or quite distinctively different.

The black pepper gastrique that you see ringing the dish gave just the right amount of spicy kick and acidity to balance the garlic aioli in the middle. A gastrique is a sweet-and-sour sauce made by caramelizing some sugar and adding vinegar. Sometimes citrus juices are cooked down to add their own fruity sweetness as well as acidity. Variations are endless, but, whatever recipe you choose to follow, a gastrique adds a real flavor punch to the plate.

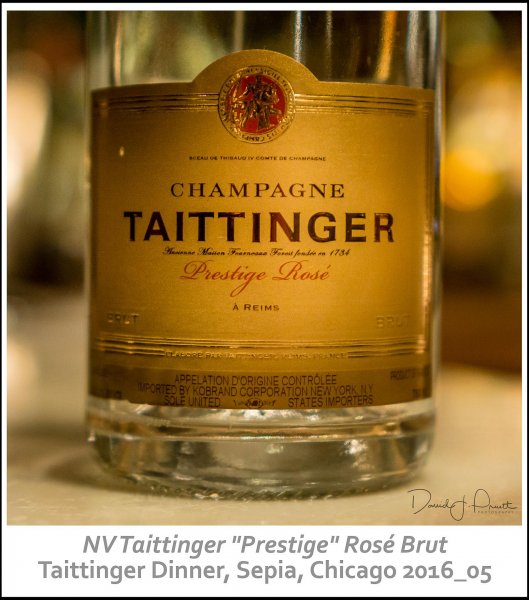

You might think that all those strong flavors would overpower a Champagne. Not to worry; there are examples of the world’s favorite bubbly that are more than up to the task, even from a house like Taittinger that specializes in a lighter, more elegant style. We needed a bit more body and fruitiness in a wine for this dish, and we got it in the two rosés that were served. First, the NV “Prestige Rosé”…

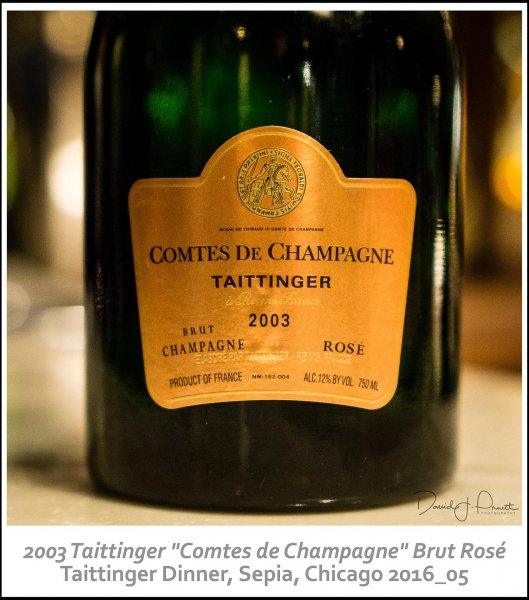

…then the 2003 “Comtes de Champagne” Rosé.

Rosé has developed a reputation, unfortunately, but not unjustifiably, as a cheap, usually somewhat sweet wine. Starting in the 1950s, Mateus, a slightly sparkling, somewhat sweet rosé from Portugal became extremely popular in the US and the UK and molded many people’s idea of what rosé was supposed to be.

In the 1970s, the folks at the Sutter Home winery in California wanted to make a more intensely flavored red Zinfandel. If you are surprised that there is such a thing as Red Zinfandel, you are not alone. Zinfandel is actually a red (actually closer to black) grape that is almost uniquely grown in California. Its origin was a mystery for many years, but it is genetically equivalent to a Croatian grape called Crljenak Kaštelanski (if you know that one, you are a much bigger wine geek than I am!). The only other place where significant amounts are grown and bottled is the Puglia region in Italy where it is called Primitivo. The problem with red Zinfandel in the ’70s was that you never knew what style of wine you were going to get. Depending on how and where it was grown, picked and vinified, it could be anything from a light, red table wine to huge, almost Port-like wine with 15% alcohol or more. By the late 70s, the market for red Zin was fading.

Back to Sutter Home and their Zin experiments. The winemaker, Bob Trinchero, removed some of the freshly pressed juice from the skins, leaving a higher proportion of the skins to color and flavor the remaining juice to make red Zin. He did not want to waste the pale, pink-colored juice he had drawn off, so he fermented it to produce a dry, lightly colored rosé. The wine was sold only at the winery as Oeil de Perdrix (“Eye of the Partridge”) a name used in France for some rosés. In 1975, the fermentation of this pinkish juice stopped (or “stuck”) before all of the sugar was fermented. A “stuck fermentation” occurs when the yeast dies before converting all the sugar in the grape juice to alcohol. The resulting slightly sweet rosé was bottles as White Zinfandel and customers loved it. It became hugely popular in the US and many wineries started produce their own version of White Zinfandel. And White Merlot. And White Cabernet Sauvignon. All of these “white” wines (also called “blush wines”) were rosés and almost all were slightly sweet with 2 or 3% residual sugar.

Most of these wines were also very fruity, often reminiscent of Fruit Punch Kool-Aid. The fruitiness and sweetness made them easy to drink for people who had not yet developed a taste for dry table wines. Most (though certainly not all) people start drinking wine with light, slightly sweet wines and later move on to drier whites, then heavier whites and then reds, later developing a taste for very sweet dessert wines that are a very different thing from the slightly sweet wines they started with. Whole generations of wine lovers started on White Zin.

There was a second benefit to the wine industry and for wine lovers that came from the White Zin boom. Remember I said that the market for red Zin was fading? Many acres of decades and even century-old Zin vines would have been pulled up and replanted if the grapes had not been sold for White Zin production. By the turn of the century, the market for fine wine had grown substantially and winemakers had learned how to make Zinfandel in more consistent styles. So, thanks to an accidentally stuck fermentation in the Sutter Home winery, a huge wine market was created, untold numbers of wine lovers began by drinking White Zin, and old and valuable grape vines have now been turned back to the production of red Zin.

What has all of this to do with Champagne? Well, there was a downside to the blush wine craze. Many people assumed that any pink wine was a fairly simple, somewhat sweet, cheap wine. When they saw a bottle of traditional, dry French rosé, whether still or sparkling, for $20+ or (in the case of some of the great rosé Champagnes) $200+, they either quickly moved back to the White Zin aisle or to the dry white or red aisles.

That move was unfortunate. Traditional dry rosés are delicious, complex, refreshing wines and are the quintessential summer wines. It is generally agreed that the rosés from the Tavel region of the Rhone Valley in France are the reference point for all other rosé wines.

Tavel is a small region in the southern Rhone that is hard to spot. Find Nîmes and Avignon at the bottom of the map and the look for a small pink spot in between and just above them. Only rosé is produced in this region, primarily with Grenache and Cinsault grapes, but, since 1969, Syrah and Mourvèdre are also allowed. All four of these are red grapes.

Many people think that rosé is made by blending red and white wines together. For most quality rosés, this is not the method used (and is, in fact, illegal in France) with one big exception, which we’ll discuss in a moment. Instead, winemakers make rosés just like White Zin is made. The red grapes are crushed and the juice is left in contact with the colored skins for a few hours (up to a day or so, more or less) and then the lightly colored juice is separated from the skins and fermented. I encourage you to try a good Tavel rosé, especially in the summer, if you enjoy dry wines. They often have a beautiful strawberry and/or other fresh fruit aromas that sing of summer.

The one exception to the French prohibition against blending red and white wine to make rosé is Champagne. High-end, Brut (dry) Rosé Champagne has only been around since the 1990s. As we have discussed, most Champagne is a blend Chardonnay (white grape) with Pinot Noir and (often) Pinot Meunier (black grapes). The black grapes are normally crushed and the juice quickly separated from the skins before it has a chance to pick up any color. To make Rosé Champagne, some of the black grapes are left on the skins as they would be to make any other red wine. Some of this red wine is then included in the final blend to produce the familiar pink color. This allows the winemaker to blend to a consistent color every year. This also, of course, complicates the work in the winery and adds to the cost of rosé Champagne.

Valeria and I both love the extra fruitiness that the red wine brings to the party. The NV Taittinger “Prestige” Rosé Brut certainly hit the spot. The nose showed several of the red fruits typical of a good rosé: strawberries, cherries, a touch of raspberry. It is made from a blend of 50% Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Meunier and about 15% of the blend is juice that has been vinified as red wine. The grapes are drawn from a minimum of 15 different vineyards, usually more, and blended to give a consistent style to every bottle. It is fuller-bodied than a typical Taittinger Champagne, which, along with the more intense fruit flavors and aromas, made it a good match with the duck. It generally retails in the $60-80 range.

Then there was the wine that, to my taste at least, is the biggest, baddest boy in the Taittinger lineup, the 2003 Comtes de Champagne Rosé. This wine is only produced in exceptional vintages and made only with grapes from Grand Cru (i.e., the very highest rated) vineyards in Champagne. 70% of the blend in Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay, and 12% of the blend is Pinot Noir that has been fermented to make a red wine. The red fruit aromas just leap from the glass—strawberries and cherries and black currants—and they are supported by floral and nutty notes. All of this is also evident when you taste the wine, as is the full-bodied character and flavors explode in your mouth (sorry for the cliché description, but it’s true). This is an expensive wine, though. If you are lucky, you might catch it on sale in the $150 range. More likely, it will be around $200/bottle and I have seen it listed at $300 and above. Those are retail prices. Restaurant wine list prices are generally twice as high or more.

The Comtes de Champagne Rosé stood up easily to the duck dish. While most people think of Champagne as something for a toast or to drink before dinner, it is not at all difficult to plan an entire meal around a series of Champagnes. The wines of only one producer were on display here; a wide array of possibilities open up when you shop across the whole range of Champagne prices and styles.

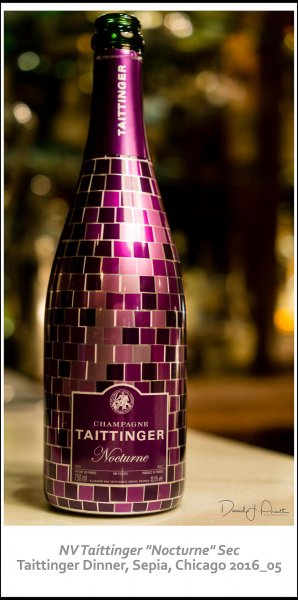

The dinner ended with what today is considered a relatively sweet (Sec, which, confusingly, literally means “dry”) Champagne, the NV “Nocturne” Rosé.

This is a relatively new offering from Taittinger and I had never had it before. It was distinctly sweet and very pink. The sweetness comes from almost 2% residual sugar which, as we have seen, is only 1/10 the amount of sugar that some Champagnes contained in the past. It is a blend of 40% Chardonnay 40% Pinot Noir, 20% Pinot Meunier. About 15% of red still wine is included in the blend to give the bright pink color, fruit flavors and aromas and body of the wine. While I am not a huge fan of sweet Champagnes, I enjoyed this at the end of the meal. It was served with some delicious mignardises. Yes, the wine even stood up to the intensely flavored little piece of dark chocolate fudge.

To sum up, there are three things that can be concluded from this dinner:

- Sepia’s cuisine is as great as ever.

- Taittinger remains a reliable producer of excellent Champagne in a variety of styles and price points.

- Planning an entire meal around Champagne is a fun and delicious thing to do.

Sepia

Address: 123 North Jefferson St, Chicago, IL 60661

Phone: (312) 441-1920

Reservations: opentable.com

Website: sepiachicago.com

Dress Code: Casual Elegant

Price Range: $50 and over

Lunch: Monday: Friday: 11:30am—2:00pm

Dinner: Sunday: 5:00pm—9:00pm

Monday—Thursday: 5:15pm—9:30pm

Friday & Saturday: 5:15pm – 10:30pm

Lounge: Opens daily at 4:30pm

Payment: AMEX, Diners Club, Discover, MasterCard, Visa

Chicago, IL 60661

The author has no affiliation with any of the businesses or products described in this article.

All images were taken with a Sony Alpha a6000 camera and a Sony-Zeiss SEL1670Z Vario-Tessar T E 16-70mm (24-105mm full frame equivalent) F/4 ZA OSS lens or Sony 35mm (52mm full frame equivalent) F/1.8 E-Mount Lens using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.