Let’s continue our travels in Cuba, shall we? We began this series of blogs with an Introduction, started diving into the details in Part 1, then stopped for lunch at El Aljibe. It had already been a long day, with a pre-dawn flight, a visit to La Plaza de la Revolución, visits to a couple of parks and a great meal. A nap would have been good, but no time for that. Our intrepid band from The Inner Circle of Halleck Vineyard were off to the Museo de la Revolución (Museum of the Revolution), driving along the famous El Malecón (officially La Avenida de Maceo) on the way.

El Malecón is a long walkway along the sea that has historically been a gathering place each night as the sun goes down and the temperature cools. Couples, young lovers, old lovers, performers and singles mingled and strolled along. It is somewhat less popular today as social media has slowly expanded and, for better or worse, made face-to-face contact less common.

El Malecón also provides great views of El Castillo de San Salvador de La Punta (The Fortress on the Holy Savior on the Point).

There’s a lot of history in the fortress, built in 1590, but we’ll get back to it in a later post when we pay a visit. For the moment, here’s a map to give you a feel for the geography. Notice that the fortress (upper right) is located on a point of land, hence that part of the name.

Cuba

Our objective for this afternoon was not far from the fortress: the Museum of the Revolution.

The building that now houses El Museo de la Revolución was built as the Presidential Palace and first occupied by President Mario García Menocal in 1920. It was used by all of the following Presidents until 1959, when President Fulgencio Batista fled and Castro and his revolutionary fighters occupied Havana. Since then, it has been a museum that primarily commemorates the history of the revolution and, to a lesser extent, the history of post-revolutionary Cuba, pre-revolutionary Cuba and the war of independence from Spain.

There are a couple of things to see before you ever enter the building. The first is a self-propelled cannon that, according to a nearby sign, Fidel Castro used to sink the Houston, an American transport ship delivering US-trained Cubans to the Bay of Pigs Invasion. (The US version is that the Houston was badly damaged by fire from airplanes and then run aground before it could sink.)

I will not attempt to recount the history or offer opinions on the Bay of Pigs (Bahía de Cochins) Invasion. Dozens of books and documentaries have been written by people who have spent years researching the event. Few would dispute that it is one of the great military and political disasters in US history. One book that appears to be quite comprehensive and as objective as these things ever are is The Brilliant Disaster: JFK, Castro, and America’s Doomed Invasion of Cuba’s Bay of Pigs by Jim Rasenberger. If you are not a reader, try the History Channel’s documentary of the event.

This map shows the location of the Bay of Pigs relative to Havana.

Cuba

The invading troops were attempting to land at the Playa (beach) Larga and Playa Girón on the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs).

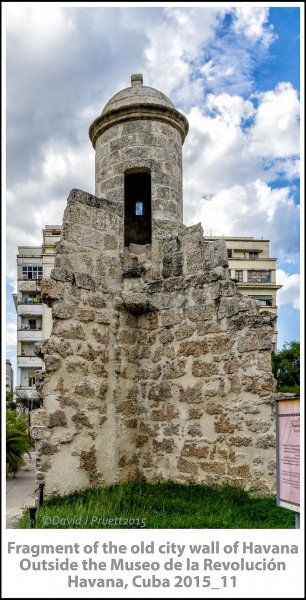

Going back to an earlier, less politically charged time in history, there is also a fragment of the old wall that once surrounded what is now called Old Havana at the entrance to the Museo de la Revolución.

There is a sign giving a brief description of the wall standing next to it, with the obligatory nod to Fidel and the revolution.

Havana was founded in 1514 or 1515 by the Spanish Conquistador Diego Velázquez de Culler, barely 20 years after Christopher Columbus landed on the island and claimed it for Spain (more on that below). As the settlement grew, various walls and partial walls were built around it for defense. The wall that defines what is now called Old Havana was started in 1674 but not completed until 1740, by which time Havana was the third largest city in the New World, bigger than New York or Boston. Only Lima, Peru and Mexico City were larger.

It is hard to overstate the importance of Havana in the New World during the time when Spain claimed much of North and South America. It had major shipyards and served as an import/export link between the New World and Europe. If this fragment of wall could talk, it would certainly have many tales to tell of Spanish, British, American and Cuban trade, conquests and history.

Just across the street from El Museo de la Revolución is La Iglesia Santo Angel Custodio (Church of the Holy Guardian Angel).

The awesome sky in the picture of the church is 100% real, not added in Photoshop. Sometimes a photographer gets lucky! Jose Martí (who, of course, you read about in Part 1 of this blog series) was baptized in this church.

OK, let’s get into the museum itself. As you enter, you are greeted by a large portrait of Fidel (as I have explained, Fidel Castro is always referred to simply as “Fidel” in Cuba—I am not being disrespectful).

While pictures and portraits of Fidel as the young revolutionary dominated the images I saw, there were some that depicted the older man. The artist, Jesús Lara Sotelo, was born in Havana in 1972. In addition to being a painter, he is a sculptor, photographer, ceramist and graphic designer. The painting was commissioned for the 55th anniversary of El Museo de la Revolución.

Entering what would have been the reception hall of the palace, there is a grand staircase featuring a bust of José Martí.

The grand entrance is majestic, but very stark. Moreover, as you climb the stairs to the bust of José Martí…

…you also see the bullet holes from the 1957 attempt to assassinate President Batista in the wall just above the sculpture.

Architectural beauty, architectural decay, signs of violence; all three are common in Havana. I live in Chicago and, sadly, this reminded me of home. We, too, have beautiful architecture, sections of town that have decayed and bullet holes from the Prohibition era right up to today.

One display that is certain to catch your eye is El Rincon de Los Cretinos (Corner of Cretins).

You probably don’t see or hear the term “cretin” very often as it is generally considered offensive. Calling someone a cretin is to call them stupid, dense and possibly mentally defective (which, to those of you of a left-wing political persuasion must sound exactly right for Presidents Reagan, Bush 41 and Bush 43, while those of you more right of center will more likely find the characterization offensive).

For each “cretin,” there is a sign that mockingly “thanks” him for his contribution to the revolución written in Spanish, English and French.

President Batista is thanked “for helping us make the revolution,” President Reagan “for helping us strengthen the revolution,” President Bush 41 “because you’ve helped us consolidate our revolution” and President Bush 43 “for helping us make socialism irrevocable.” To the best of my knowledge, none of these former Presidents has ever commented on this “honor.” (I have seen more recent photos of this exhibit in which these rather cheap looking signs have been replaced by bronze plaques.)

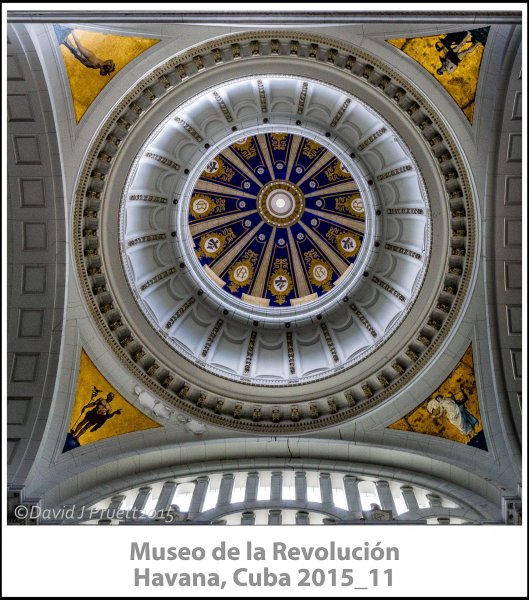

When visiting grand buildings of any kind, it is often important to look up. That was certainly the case in this former palace, and looking up in the foyer/grand staircase give you a look at this artistic detail:

The colors and shapes in this cupola are beautiful, despite the fact that it could use a good cleaning, as is more evident in this wider view.

There are a number of busts located around the museum, some of expected historical figures and some less expected. It was not surprising to see a bust of Simón Bolívar.

Bolívar is one of the most important and revered figures in Latin American history, though, like all significant historical figures, there are those who criticize both his personal and public life. He was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1783. He grew up an admirer of both the American and French revolutions, with a vision of ending Spanish rule and slavery across North and South America. Beginning around 1808, Bolívar first participated in and eventually led various coups, rebellions and military campaigns to establish Venezuela as a free state. There were a number of twists and turns along the way, but Venezuela became an independent country in 1821. The official name for Bolivia today is the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (República Bolivariana de Venezuela).

From there, Bolívar went on to oust the Spanish and create independent countries in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia and Panama. Bolivia, obviously named after Bolívar, was carved out of what was then northern Peru. Bolívar served as President of most of these individual countries and also of a union of these independent nations called Gran Colombia. The union was not to last, however, despite Bolívar’s impassioned plea to preserve it as he stepped down from the Presidency in 1830. He intended to move to Europe, but died of tuberculosis at 47 evan as his luggage was being packed for the trip.

That is a very brief and simplified version of Bolívar’s life. He is a major, very interesting figure in the history of the Americas. If you haven’t learned much about him in the past, I recommend Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie Arana as a very readable account of his life from a Latin American perspective (which can be very different from a Spanish perspective).

Not far from Bolívar is a bust of Christopher Columbus (Cristobal Colón in Spanish).

Columbus was hailed as a hero for several centuries as the discoverer of the New World. More recently, he has been reviled by some as a cruel, genocidal slave-trader. Entire books have been written offering various viewpoints on what he did and did not do and how he should be regarded. I will not try to sort all of that out here, except to say that, given the politics, religious views and societal norms of the times he lived in, there is an element of truth in all these viewpoints. For an excellent “classical” look at Columbus and his voyages, Admiral of the Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, by Samuel Eliot Morrison, which won a Pulitzer prize over 70 years ago, is a great read. For the more recent “Columbus was a bad guy” viewpoint, try Lies My Teacher Told Me About Christopher Columbus: What Your History Books Got Wrong, by James W. Loewen.

Columbus could not have “discovered” North America in the broadest since of the word, since there were obviously already people living there. Nor was he the first Western European to arrive there. That honor, according to the best current scholarship, goes to Lief Erickson and the Vikings, who established the first settlements in the northeast of what is now Canada in c. 1000 A.D., though these settlements never became permanent. (If the old Norse Sagas are reliable, there was actually a merchant named Bjarni Herjólfsson who spotted the North American Mainland in 986 A.D. when his ship was blown off course. Two unnamed men are reported to have been shipwrecked there and were rescued by Lief Erickson when his ship was blown off course and he made his first sighting of North America, which led to his organizing an expedition and subsequently founding settlements there.)

Still, no one in Europe knew that North and South America existed (the Vikings just thought they had landed on part of the Arctic) and Columbus’s voyages did lead to the permanent colonization of the “New World” by Europeans. He landed on what we now call Cuba on his first voyage, so his bust in Havana is quite appropriate.

Perhaps more unexpected is a bust of Abraham Lincoln.

Almost from the moment the United States became an independent country, it was assumed by many that Cuba, then controlled by Spain, would eventually become part of the USA. The geographical proximity and economic ties between the US and Cuba made this seem pretty obvious (except, perhaps, to the Spanish). Early American Presidents considered annexing the island militarily, while later Presidents attempted to buy the island from Spain.

During Lincoln’s time, Cuba figured prominently in the debate about slavery. Cuba, like the Southern States, was highly dependent on a plantation slavery economy. You may recall from your American History classes that the Missouri Compromise of 1850 stipulated that as western states came into the Union, those south of latitude 36° 30′ (which is the border between Missouri and Arkansas and Kentucky and Tennessee) could be slave states while those north of that parallel must be free states. Slave states, who were outnumbered, continued to look for ways to bring more territories where slavery would be permitted into the United States, with Cuba to be the first among many in Mexico, Central America and South America. In 1861, just as Lincoln became President, there was a very strong effort to pass Constitutional amendments that would have made slavery legal in any future states south of 36° 30′ and remove all Congressional power over slavery in these areas. Lincoln and his Republican Party defeated this Democratic effort, but barely.

In the 19th century there were groups of British buccaneers who sailed in search of Spanish gold and silver. They were called “filibusters” (not to be confused the modern use of the word referring to stalling and blocking tactics in Congress). Filibusters also sailed from the United States, mostly illegally, some with a wink and a nod from the government, in attempts to acquire wealth or land. Between 1848 and 1851, a Cuban expatriate named Narciso López lead 4 filibusters attempting to drive the Spanish from Cuba and create two or more American slave states from it. All his attempts were thwarted and he was captured and executed on his last attempt. Lincoln’s staunch opposition to López and to slavery and its expansion is stilled admired by the Cuban people.

Less well known to most Americans is Benito Juarez.

Benito Pablo Juárez García (1806—1872) was President of Mexico from 1861-1872. He is widely regarded as a national hero who led a movement to change Mexico from a country ruled by aristocrats and the Catholic church to a pro-capitalist, democratic republic. Juarez was not Spanish, but Zapotec, an ancient, pre-Columbian civilization that flourished (peaking around 200 AD) in the Oaxaca region of what is now Mexico. He and his associates overthrew President Santa Anna (the General Santa Anna who took the Alamo), disbanded the separate legal system for clerics and soldiers and confiscated much of the church’s property. A new constitution was enacted in 1857. These reforms sparked the Reform War (1858—1861) between Juárez’s liberal party and a conservative movement led by the Church and some members of the military.

The liberals eventually won the day but at great cost to the economy and infrastructure of Mexico. They found themselves in deep debt to England, Spain and France, who planned to intervene in Mexico to protect their investments. All three countries landed troops in Mexico, but Spain and England soon realized that the French, under Napoleon III, intended to conquer Mexico. Juárez negotiated an agreement with Spain and England and they withdrew, but France continued its invasion and set up Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian von Hapsburg of Austria and his wife, Carlota, as Emperor and Empress of Mexico. Juárez and his allies kept their government together and continued to resist the French occupation. Cinco de Mayo is a celebration of a Mexican victory over the French at the Battle of Puebla in 1862.

In 1867, the French troops withdrew from Mexico. Maximillian was soon captured and executed and Juárez and his government in exile returned to Mexico City. Juarez was re-elected President in 1867 and 1871, but he died of a heart attack in 1872 as his last term was just beginning.

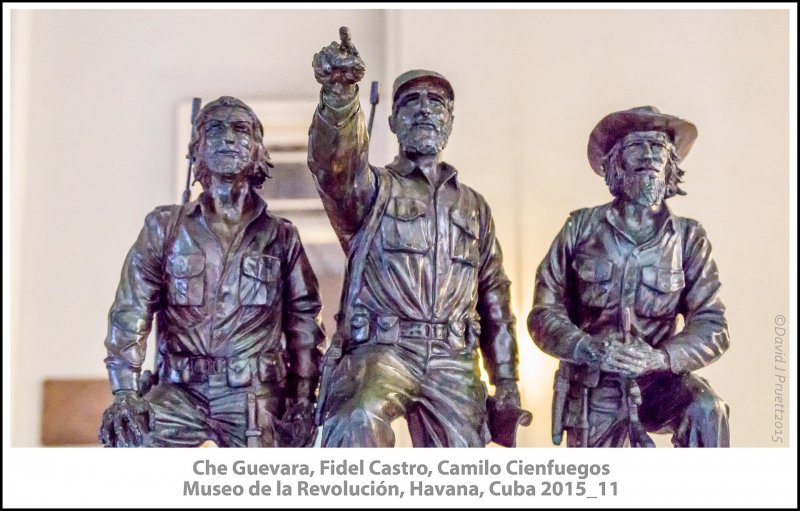

There is no shortage of homages to Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos and, of course, Fidel Castro in the museum.

This statue seemed appropriately sophisticated to me, while some of the dioramas reminded me of the sad exhibits that used to be common in even such great museums as the Smithsonian.

Maybe it’s just me, but I find these to be a bit cheesy. Be that as it may, you’ll find lots more information about these three revolutionary leaders in Part 1 of this series, Cuba: Day 1 Part 1.

There are plenty of artifacts from the Revolution in the museum, including clothes and uniforms (some with blood stains), radios, cameras, newspaper clippings and so on.

There are also displays honoring less well known, at least to non-Cubans, revolutionaries such as Vilma Lucila Espín Guillois and Celia Sánchez Manduley.

Vilma Espin met Raul and Fidel Castro when she served as a messenger to them while they were exiled in Mexico planning their return to Cuba. She and Raul married in January, 1959 and remained married until her death in 2007. She held a degree in Chemical Engineering that she earned in the 1950s (unusual for women in those days) and held a variety of important positions in the Castro government.

Celia Sánchez was a messenger and a fighter during the Revolution and became a major archivist of the Revolution and subsequent events until her death in 1980. She was a very close friend of Fidel’s, though just how close is a matter of some speculation. Fidel had two wives but was faithful to neither, with several known mistresses before, during and after his marriages. It is not clear if Sánchez was one of his paramours.

However you may feel about the Revolution, Fidel or Socialism, the history of Cuba is undeniably important to the history of the New World. The museum is not air conditioned and the light and dust from the open windows is hastening the decay of the historical artifacts and exhibits in the museum. I do hope that money is found to control the climate in the museum and place the artifacts in displays that will better preserve and explain them. All but a few of the signs in the museum are in Spanish only. Adding an English and French translation, as they did for the Rincon de los Cretinos would make the museum far more interesting and accessible as tourism expands beyond visitors from Latin America.

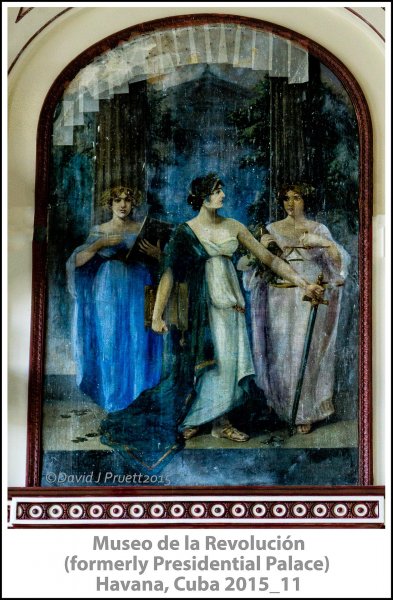

There are hopeful signs of restoration in the building. The main ballroom, which once must have been magnificent, is being restored. There is a beautiful fresco on the ceiling as well as several beautiful paintings on the walls, most of which were obscured by scaffolding and drop cloths on the day we were there.

As you step out of the museum, the contrasts that characterize Cuba are all around. First, you can look back at the museum building itself.

Just across from the museum, however, is a building with chipping plaster and laundry hanging out to dry—a reminder that a washer and dryer is a luxury most cannot afford in Cuba.

Then one of the classic old cars goes by in a race with a bicycle taxi.

And while money may be scarce in Havana, talent is not, whether for music, dance or art.

At last, our long day of travel and touring was over. As we drove back to the hotel, we passed the newly reopened United States Embassy in Havana, which had been open less than two months when we arrived. We never stopped near it, so the best I could do was a grab shot through the window of the bus.

Our home during our stay in Cuba was the Hotel Meliá Cohiba.

The map shows the location of the hotel (upper left), the Plaza de la Revolución (lower middle) and the Museo de la Revolución (upper right).

This is a very nice hotel and, by all accounts, one of the best in Cuba. One of the issues facing Cuba as it opens up is the shortage of fine hotels. (Our travel agent, Cuba Explorer, indicated that essentially all of the better hotels were booked out at least 5 months in advance.) It is close to the airport and most everything you want to see in Havana. There are several restaurants to choose from, as well as a quiet lobby bar, a jumping club-style bar and a cigar bar.

I’ll share more about the hotel in future chapters of this account but we’ll end this one with a look at the buffet dinner in La Plaza Habana. This is the hotel’s largest dining area where buffet breakfasts, lunches and dinners are served. While buffets are never my favorite, after a very long day of travel and touring, eating in the hotel with a minimum of fuss was perfect. The meal was made special by the three bottle of Halleck Vineyard wines (2 Pinot Noirs and Little Sister Sauvignon Blanc) that Ross Halleck placed on each table.

I’ve included more photos of most of the buffet stations in the gallery at the end of this blog, but selections included soup…

…salad…

…paella…

…pizza…

…fish…

…chicken and beef…

…and, of course, dessert!

As I said, I am not a fan of buffets in general, but this one was about as good as they get. Certainly the variety of choices offered was extensive, and anyone from the most dedicated vegan to the most committed carnivore could find more than enough to eat.

By the time we finished the last of our wine we were more than ready for bed. The next day would see us off exploring the old city, visiting rum and cigar shops and factories, witnessing the canons being fired at El Castillo de San Salvador de La Punta (The Fortress on the Holy Savior on the Point) and, of course, more Halleck wines and some much more interesting Cuban food. Join me in the next segment!

Take a few minutes to browse the images in the slideshow. There are many that are not included in the article above.

The author is a member of the Halleck Vineyard Inner Circle Wine Club but otherwise has no affiliation with any of the places, companies, equipment or locations mentioned in the article.

All images were taken with a Sony Alpha a6000 camera and a Sony-Zeiss SEL1670Z Vario-Tessar T E 16-70mm (24-105mm full frame equivalent) F/4 ZA OSS lens, Sony SEL1018 10-18mm (15-24mm full frame equivalent) F/4 Wide-Angle Zoom Lens, or Sony 18-200mm (24-300mm full frame equivalent) F/3.5-6.3 E-Mount Lens using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.

Ross Halleck

8 Jun 2016Great coverage of the day, but most elucidating view of history to flesh out the significance of all we saw and experienced. Photos, of course, stunning. Especially liked the one of Valeria in a snapshot of innocent beauty in front of the Museo. Thanks for this great contribution to our experience and carrying it forward. I look forward to more, though I understand the huge time and effort this takes. Olé! y Gracias!