Let’s spend some more time on the Burgundy Canal, shall we? If you have read the previous entries in this series, you know we are ending our first full day of cruising aboard La Belle Epoque. What? You haven’t read the previous chapters? Shame on you! But, no worries! You can catch up here:

Day 1, Part 1, Paris to Tanlay

Day 2 Part 2, Tanlay to Lézinnes

We ended the last chapter as the ship was docking in Lézinnes. One of the great features of the European Waterways cruises is the fact that one or more vans (always enough to accommodate everyone on the cruise without crowding) follow the ship as it sails and are available whenever needed for side trips from wherever the ship is docked. The crew somehow manages to take care of things on the boat while moving the van(s) each day as well. Sure enough, they were waiting for us dockside in Lézinnes.

Not long after we docked we were asked to board the vans for an excursion to Chablis. It’s always your choice to go with the tour, relax on the boat, or grab a bicycle and head off on your own, but I don’t think anyone on our trip ever regretted going on one of the planned excursions. After all, the crew had had all summer to find the best places and learn all about them so they could share the most interesting bits with us.

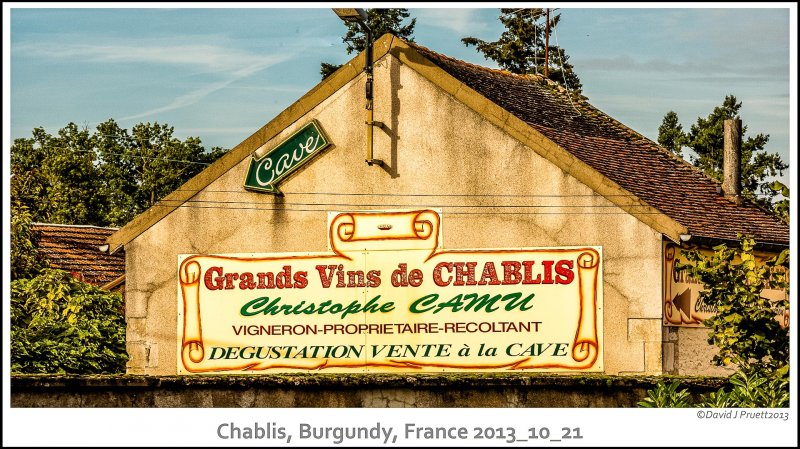

Chablis is a name that is familiar to many people as a rather light white wine. If you grew up in the United States, you may remember lots of California wines being labeled “Chablis” (as well as Burgundy, Chianti, Port, etc). After Prohibition ended, but before the 1970s, wines made in the United States were generally considered inferior to their European counterparts because, well, they were. Winemakers at that time used a lot of easy-to-grow grapes like Thompson seedless, the green grapes you see in every grocery store, to make wine. While these grapes can be tasty enough as a snack, they have none of the complexity of the traditional European wine grapes that have been developed and refined for winemaking over centuries. So, cheap wines were named after a region that was known for making good wines in Europe. “Chablis” was the name placed on most cheap, usually sweet, gallon jugs of white wine, “Burgundy” on light, dry reds, “Port” on sweet reds and so on. If you grew up on these wines and didn’t know any others, that was probably fine.

However, in the 1970s winemaking in the US, first in California and then in other states, really took off in both quality and quantity of wines being made from traditional winemaking grapes (vitis vinifera for you botanical types). Interest in fine wines from Europe grew rapidly as well. It did not take long—one sip was enough—for people to realize that the wines from Chablis in France, Chianti in Italy, etc., had no resemblance at all to the jugs of wine with the same name being produced in the US. Fortunately, through a series of international and domestic wine law changes, as well as US winemakers wanting to distinguish their own, now often delicious, wines, this generic labeling has pretty well ended.

So what is “real” Chablis? It is almost alway made with 100% Chardonnay grapes. That is the same grape that is used to make rare, expensive, White Burgundies in France and big California Chardonnays. The grape has also found homes in Australia, Chile, and Italy, among other places. Some of these wines are delicious, some mediocre and some downright poor. So many bad and mediocre Chardonnays have been produced in California that an ABC (Anything But Chardonnay) movement was started. Still, when Chardonnay is grown in the right place, the weather cooperates, and the grapes are skillfully vinified, it produces some of the most delicious and age-worthy white wines on the planet.

Chablis is actually the northernmost wine district in Burgundy and so is technically “White Burgundy,” too. Because the region is relatively far north, the grapes struggle to get enough light and heat to fully ripen. That means the resulting wines are light, relatively high in acidity and, when well made, wonderful as aperitifs or with things like gougeres (cheesy pastry bites – yummy!), strong cheeses, raw shellfish, smoked white fish and sometimes even ham. (As always, your own taste may vary and prefer other combinations.)

In addition to the climate—living on the edge–the soil in Chablis, at least in the best vineyards, is unique. Chablis is located in an area that was once a sea. When the water left, a layer of limestone and clay soil that is full of seashells and fossilized bits of marine life was left behind. Good Chablis often has a flavor of the sea and seashells. For the skeptical scientists among you (a description that often applies to me) it is not obvious how a seashell in the dirt can produce these flavors in the wine, but it seems real enough. The difference between a light, minerally, Chablis and a big, oaky, butter Chardonnay from the Napa Valley is like the difference a piccolo and a tuba; they are both brass instruments but the similarity ends there.

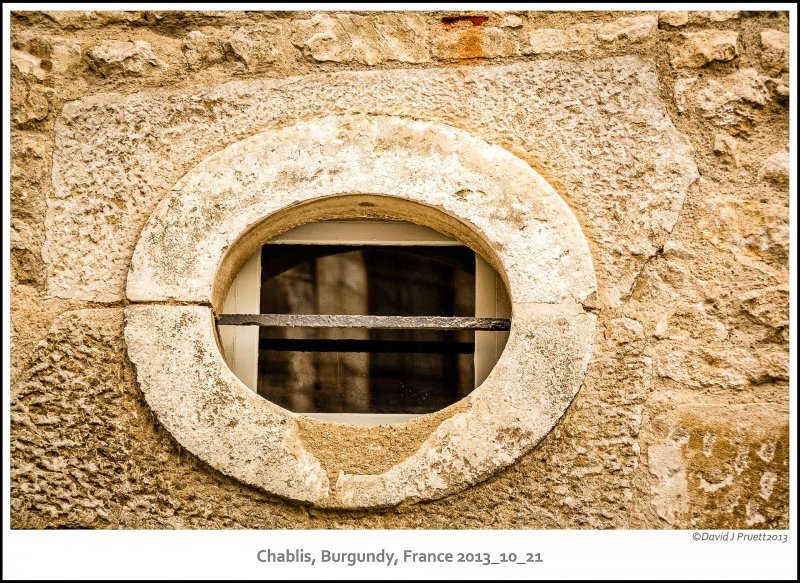

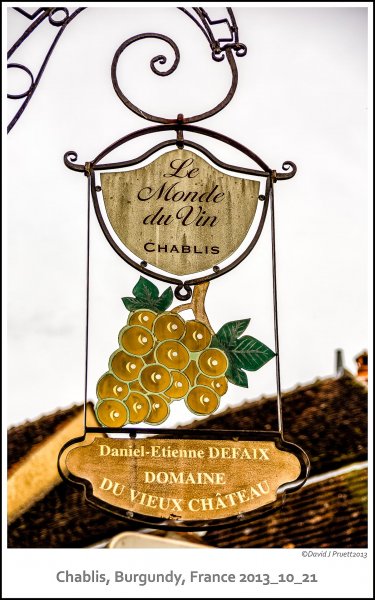

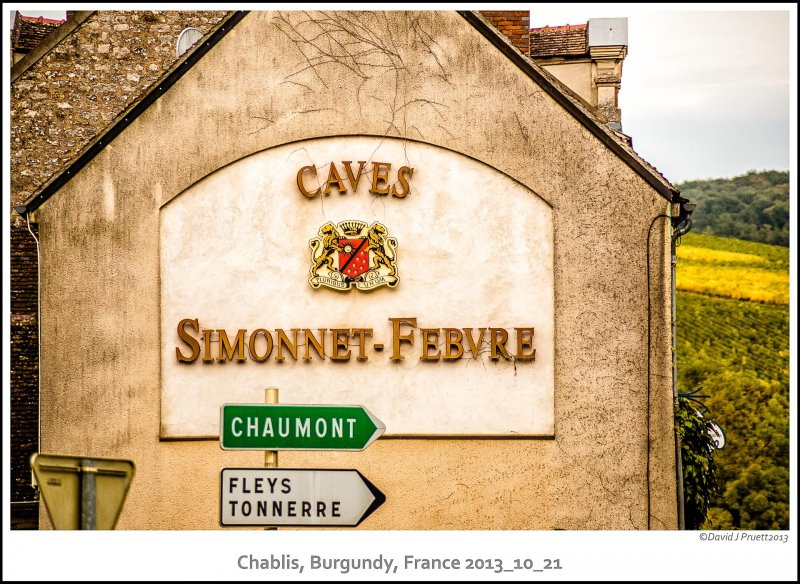

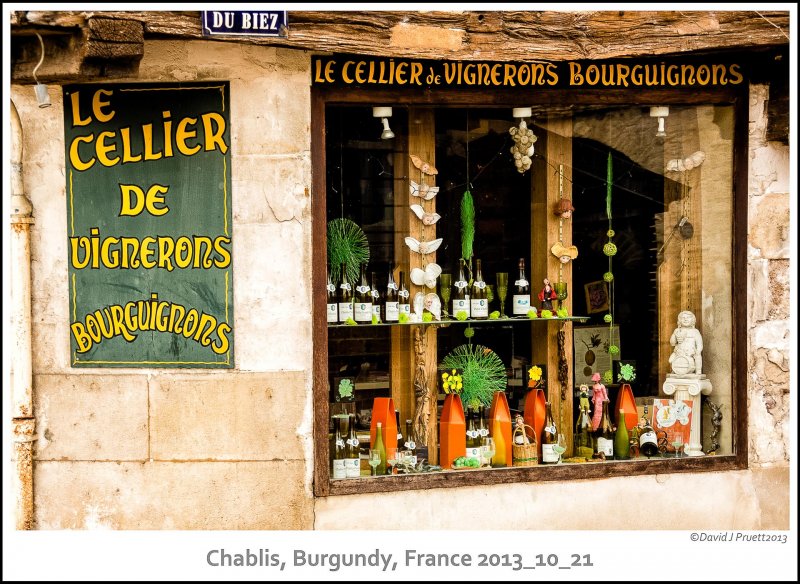

As you will see, Chablis, the village, is beautiful and very picturesque.

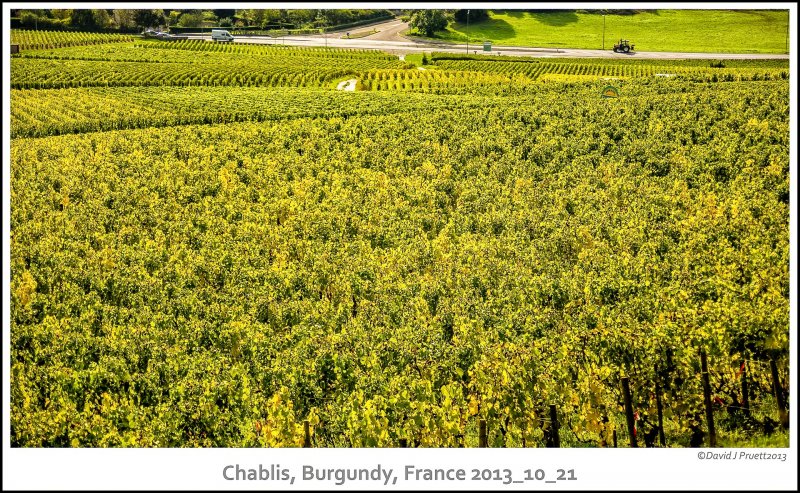

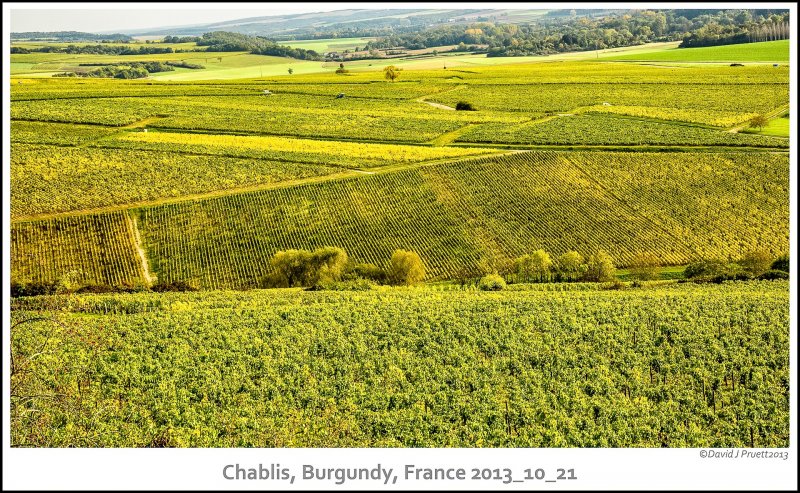

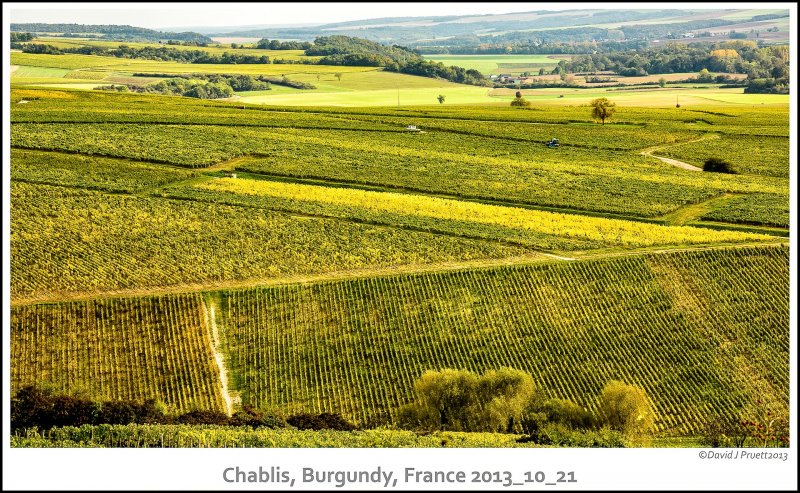

But we’ll get to that later. Before we spent time in the village of Chablis, Anna Markham who, as usual, was leading the tour, took us to the heart of Chablis: its vineyards.

The important thing to note in the picture above is that we are standing on top of a hill facing southwest overlooking the town. As with all wine regions, not all the vineyards in Chablis are created equal. Some sites have better soil, more light, are a bit warmer or have other attributes that make the grapes grown on that spot a little (and sometimes a lot) better for making wine than grapes grown just a few yards (meters) away. In France, the vineyards that consistently make the every best wines are called Grand Crus. All of the Grand Crus of Chablis are located on the slope we were looking down from. They are shown clearly on this map, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

A notch below the Grand Crus are the Premier Cru (abbreviated 1er Cru) vineyards. Technically, there are 40 different Premier Cru vineyards in Chablis. One of the quirks in French wine law allows lesser-known vineyards to use the name of nearby, more widely-known vineyards at a (theoretically) equal quality level. Thus, almost every bottle of Premier Cru Chablis will be labeled with one of 17 Premier Cru Vineyard names: Les Beauregards, Beauroy, Berdiot, Chaume de Talvat, Côte de Jouan, Côte de Léchet, Côte de Vaubarousse, Fourchaume, Les Fourneaux, Mont de Milieu, Montée de Tonnerre, Montmains, Vaillons, Vaucoupin, Vaudevey, Vauligneau or Vosges. Compared to the Grand Crus, these wines will generally be just a tad less alcoholic and a little less complex in aroma and flavor.

You will also find wines designated simply “Chablis” or “Petit Chablis.” These wines come from vineyards outside of the Grand and Premier Cru areas. While they can be much less expensive than Grand of 1er Cru wines, they are not necessarily good values. The area in which vineyards could legally be called Petit Chablis or Chablis was great expanded back in the ’50s, often into areas that bear little resemblance in soil and microclimate to the traditional Chablis vineyards.

If you look closely at the picture of four wine bottle earlier in this post, you’ll see (from left to right) a Petit Chablis, a Chablis, a 1er Cru and a Grand Cru. It would be nice if quality increased reliable with the designation and the price but, as everywhere else in the wine world, it just doesn’t work that way. While it is certainly true that the grapes and the resulting wines have the potential to be consistently better as you move up the scale, growers and vintners do not always do their work with the same skill. Even Mother Nature can sometimes throw a curve in a given year and confuse things even more.

Nevertheless, there are those that argue that a great Chablis is the finest expression of the Chardonnay grape. While I would not go that far, I certainly do love good Chablis.

So, we spent a little more time admiring the Grand Cru vineyards from our perch on tope of the hill…

…until finally it was time to come down and taste some wine. First, a short drive through the village…

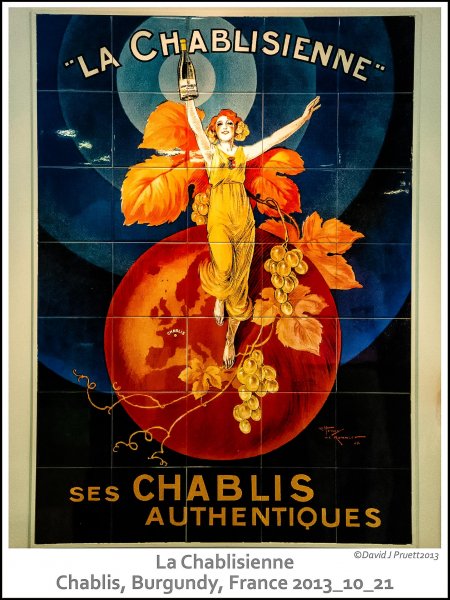

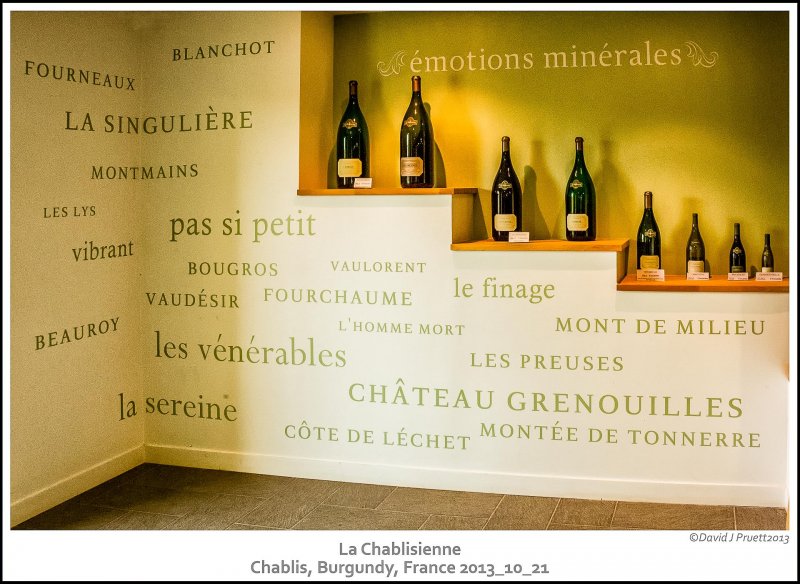

…then to the home of the large Chablis wine co-op called La Chablisienne.

First formed in 1923, almost 300 growers in the Chablis area bring their musts (grapes that have been crushed into a mixture that contains all the juice, skins, seeds and sometimes stems) to La Chablisienne. Once there, the musts are fermented, aged and the resulting wines blended, bottled and sold. The farmers and the technical staff of the co-op work together to produce the best wines they can.

Their modern headquarters is ready for visitors. It has a large tasting bar…

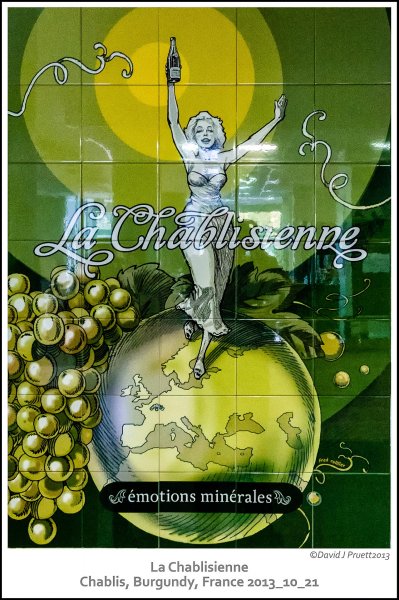

…displays of some of the great posters they have produced over the years…

…and, of course, plenty of beautifully packaged wine to sell!

We enjoyed a tasting of four wines while we were there.

I’m sure you noticed right away that they poured one wine from each of the major designations (Petit Chablis, Chablis, 1er Cr and Grand Cru). I’ve been pretty wine geeky so far in this post, so I’ll spare you detailed wine tasting notes and just say someone had done a good job in selecting these wines. They were are very good, and increased clearly in weight and complexity as you moved up the scale. While it made no sense for us to buy wine here and carry it around France for a week then fly it back to Chicago, I have to say that Valeria and I have drunk Chablis far more often since we were there.

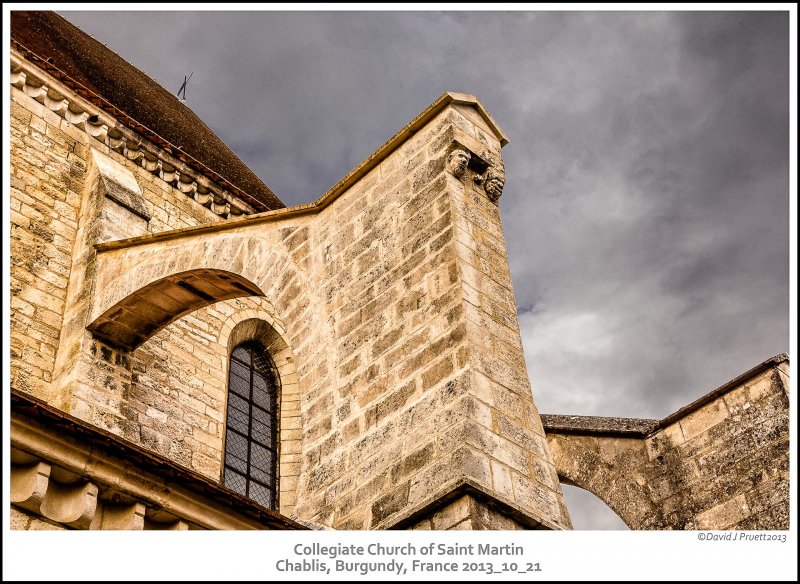

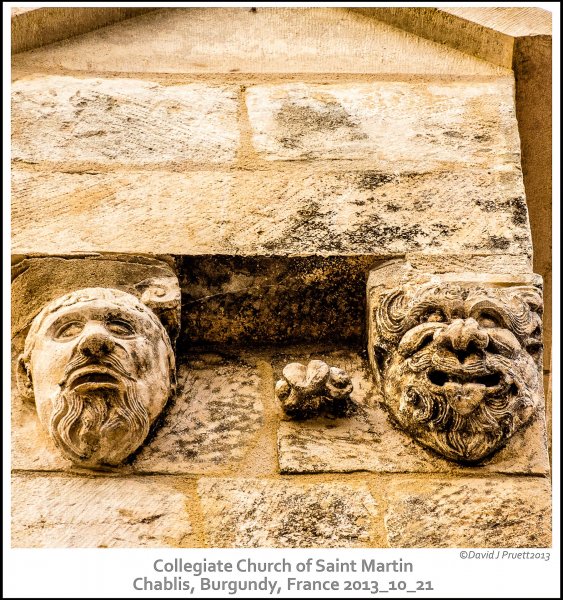

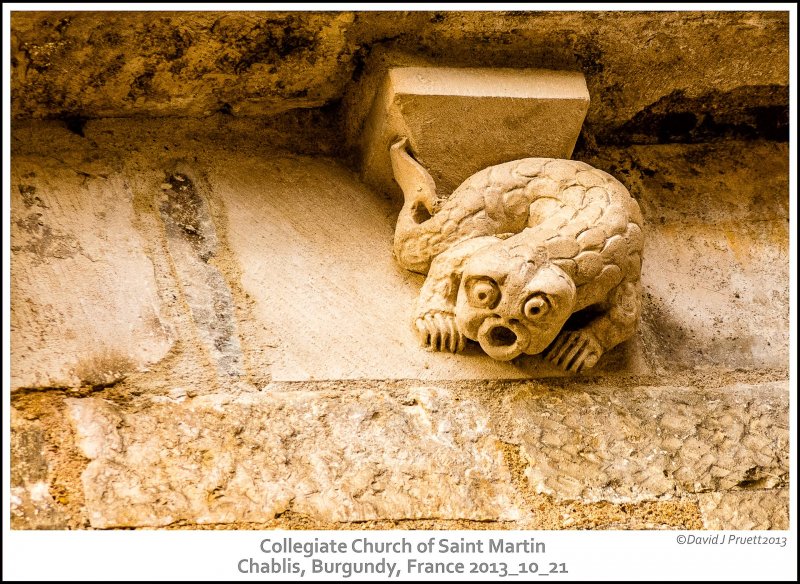

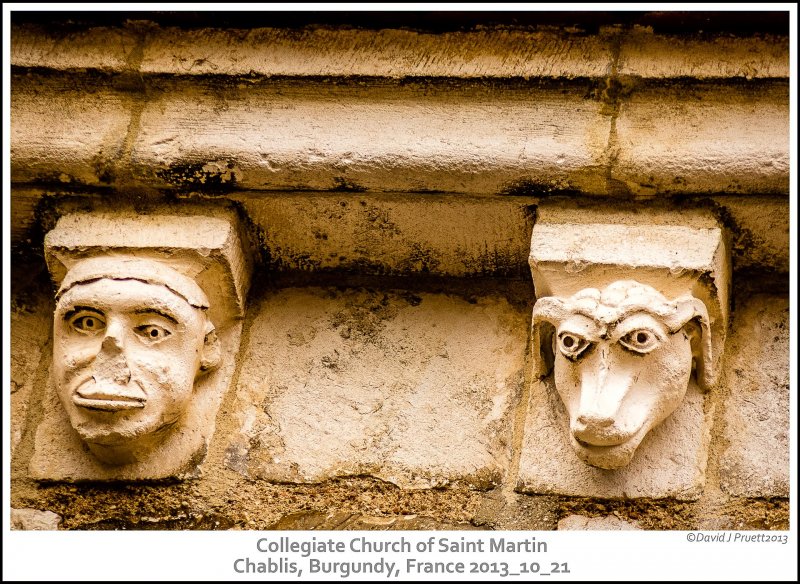

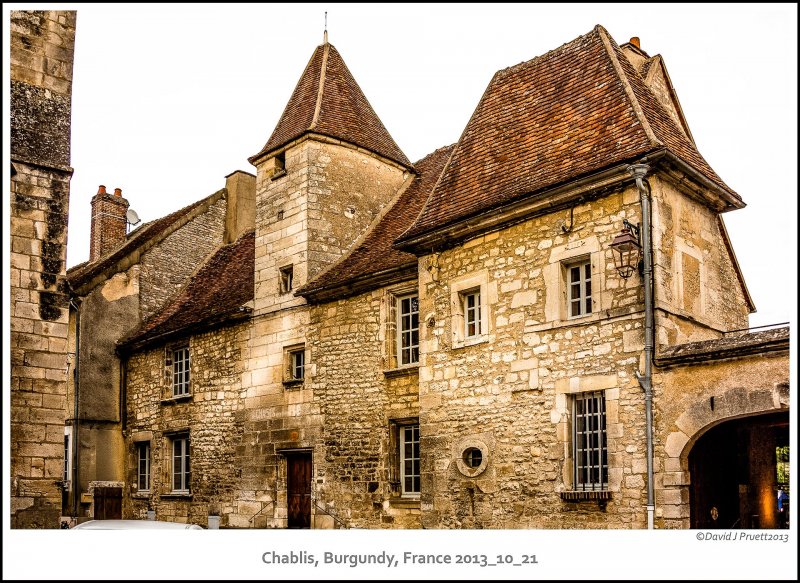

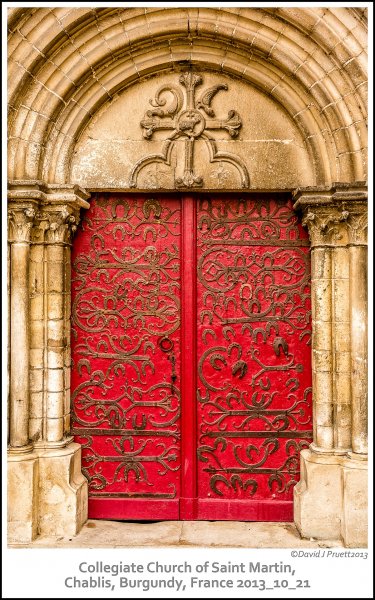

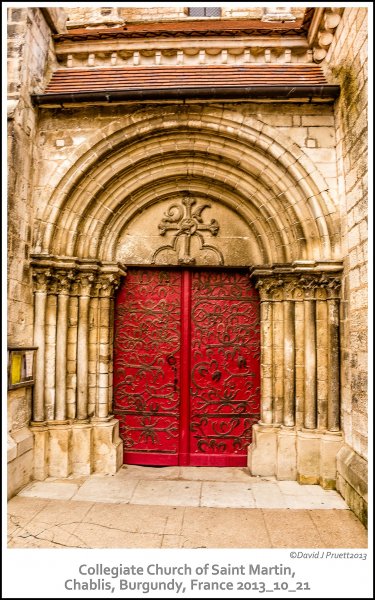

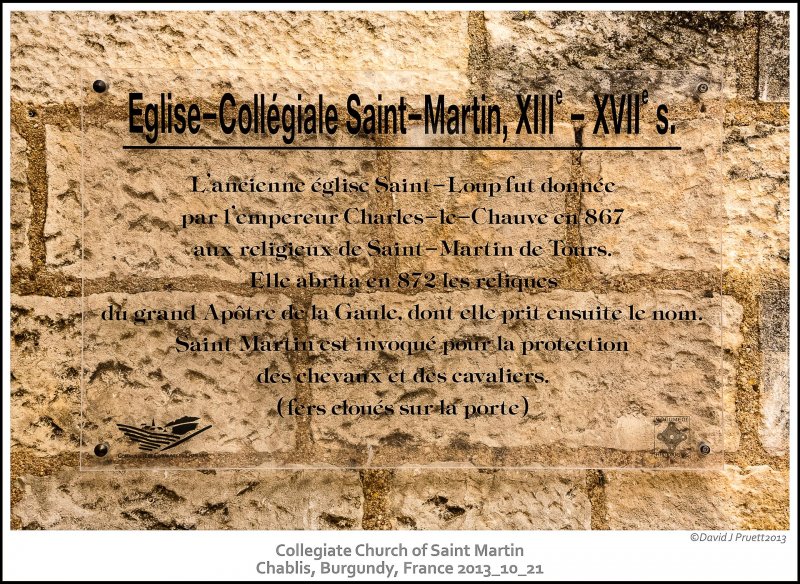

After the organized tour of the vineyards and tasting, we were left on our own to wander the streets of Chablis for a while. One of the landmarks of the village is the Collegiate Church of Saint Martin.

The Romanesque-stye church was built in the early 13th century and dedicated to Saint Martin, the patron saint of horses and horseman. The church has remained largely unchanged since it was built, with the exception of the bell tower that was added in 1852.

Chablis is a pretty quiet village, at least the day we were there. Even the cats were just chilling.

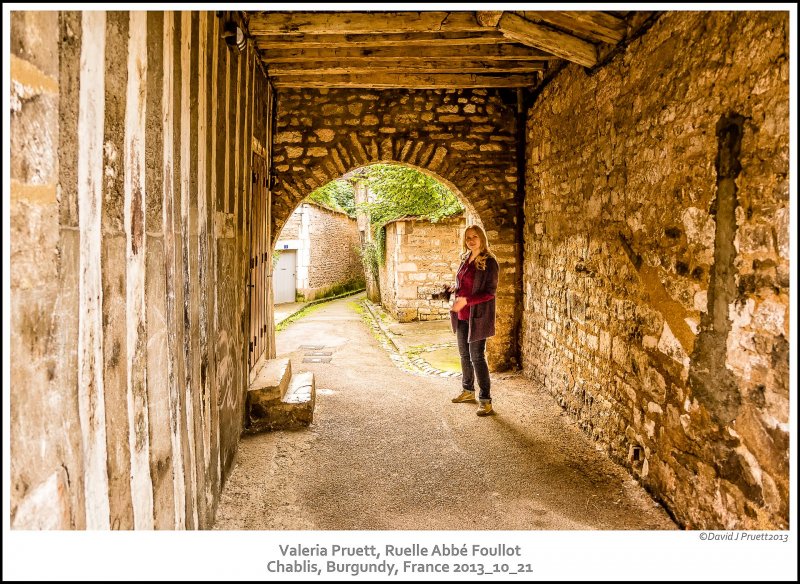

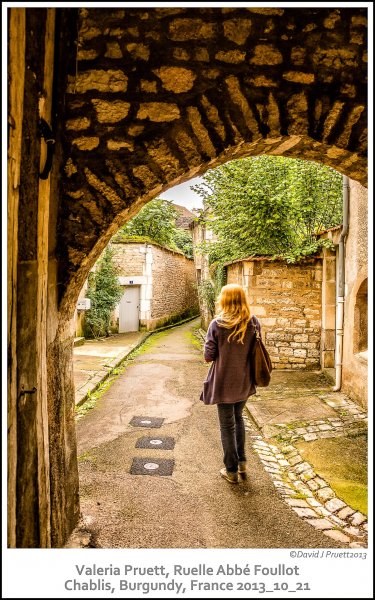

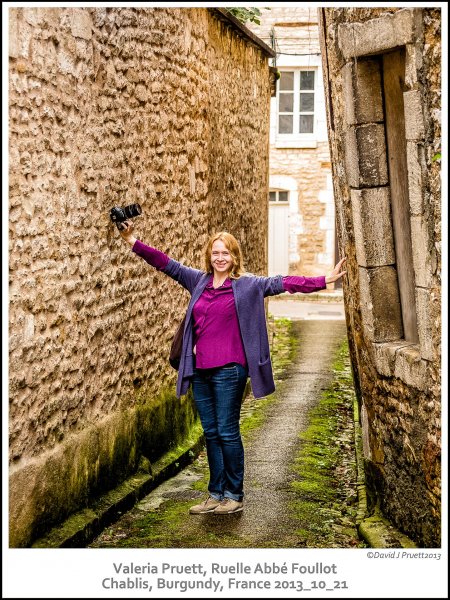

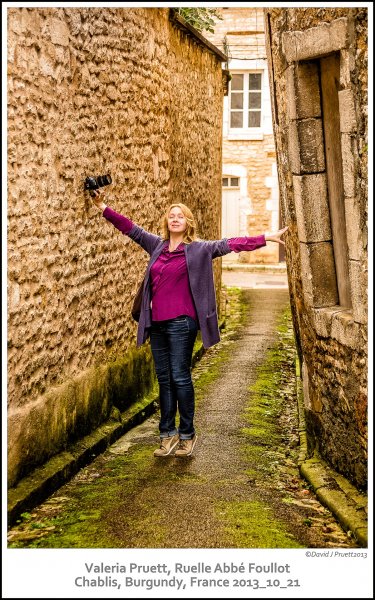

Near the church there was an old, narrow, covered street called Ruelle Abbé Foullot. It gave you the feeling of walking down an old medieval street, which, in fact, you were. It is only about 50 meters (55 yards) long.

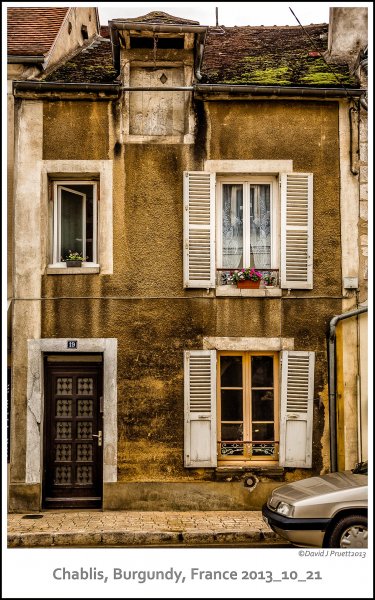

Most of the buildings in town appeared to be quite old and built of weathered stone and stucco. Some homeowners made up for the dullness of the walls with brightly colored doors, shutters and flowers.

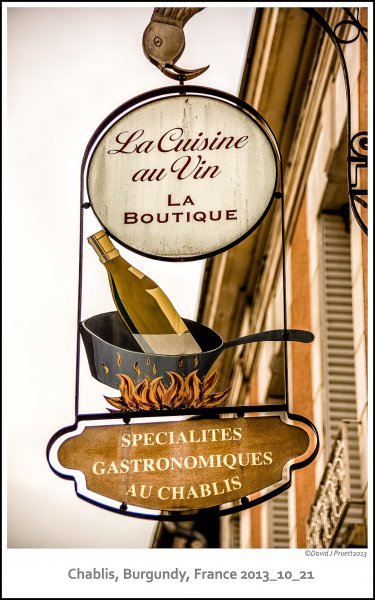

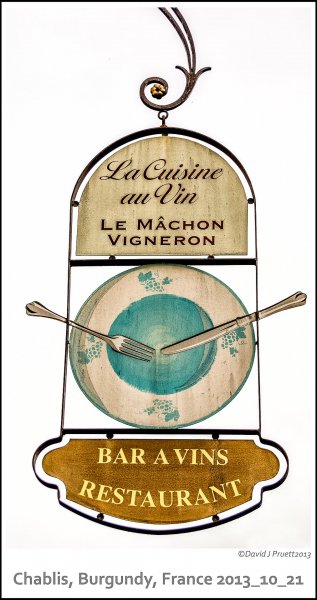

Not surprisingly, the restaurants in town advertise their skill with food, because it was France, and their skill with wine, because it was Chablis.

Of course, if you wanted to make you own meal, their was no shortage of places to buy great ingredients.

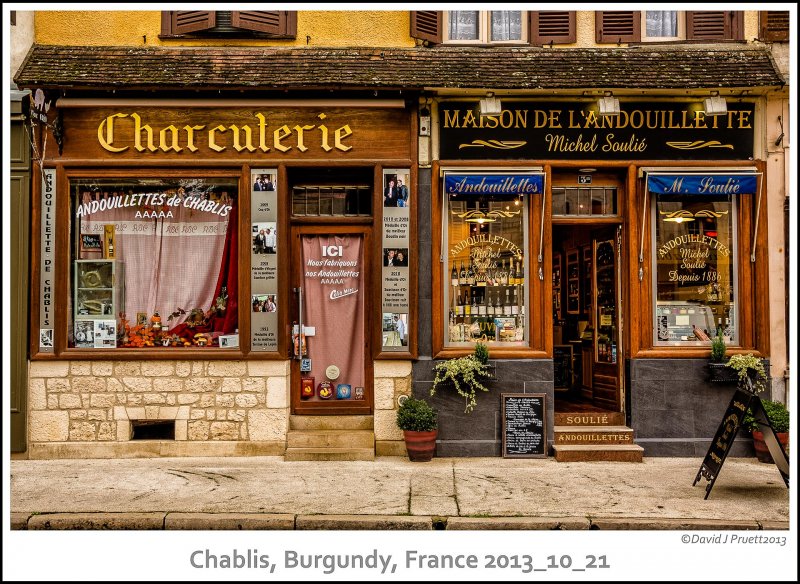

The Maison de L’Andouillette might make you think it is a sausage shop selling something like the wonderful andouille sausage that is a key ingredient in the delicious gumbos made in Louisiana cajun cuisine. Well, you would be close, but not real close. Andouille is made with pork, usually tougher cuts like the shoulder and shank, that is generously seasoned with salt, pepper, garlic and a variety of herbs and seasonings that individual sausage makers keep secret. It is then smoked. Andouillette is a rustic ancestor of andouille. It is traditionally made with the small and large intestines of pigs and cow tripe (stomach). The sausage that results is generally much courser in texture than andouille, as the meat is chopped instead of ground. It is generally served hot (although it can be eaten cold) after being boiled or grilled and accompanied by onions and strong mustard. It has a distinctive and, to people living outside of the areas in France where it is appreciated, quite strong and unpleasant odor, especially when the large intestine is used. I have tried it and managed to finish a small serving. Suffice it to say that it is an acquired taste that I have not made an effort to acquire.

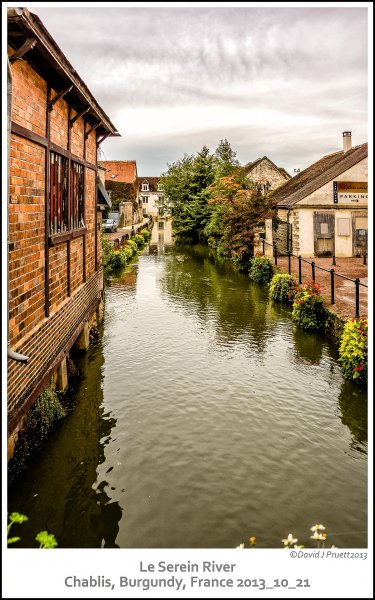

The village is built around Le Serein river, which offers some beautiful views as it winds through town.

The view is even prettier when the water is lined with colorful flowers…

…or framed behind a lovely lady.

It was time to return to the vans and, in them, to La Belle Epoque. After all, Chef Katy was making dinner and we wouldn’t want to miss that!

As we drove back to the dock, the road was blocked by a farmer hauling grape vine clippings with a modern, but very slow, tractor. It was a nice reminder that not everyone, everywhere is in a hurry.

Our time in Chablis taught me once again how much more you can connect with a wine when you have stood on the ground in which the grapes are grown and talked to the people who make it. If you ever have the chance to get out and explore the French countryside, do visit Chablis. Definitely try the wines. Sample the andouillette at your own risk!

The gallery contains some images not shown in the blog entry.

All images were taken with a Canon 5D Mark III camera and a Canon EF 24-105mm f/4 L IS USM Lens or a Tamron AF 28-300mm f/3.5-6.3 XR Di LD VC Aspherical (IF) Macro Zoom Lens (now discontinued; replaced by Tamron AFA010C700 28-300mm F/3.5-6.3 Di VC PZD Zoom Lens) using ambient light. Post-processing in Adobe Lightroom® and Adobe Photoshop® with Nik/Google plugins.

The author has no affiliation with European Waterways or any of the locations and products described in this article.

Lee

4 May 2016Wonderful David! You brought to life a wonderful time. So enjoyed your beautiful photography and description….learned a lot ! All my best to you and Valerie. Cheers, Lee